"It didn't look serious. It looked like a prank."

Those were the late David Bowie's first impressions of Memphis, a collective of young Milanese architects and designers that revolutionised the industry in the 1980s. "It mixed Formica attitude with marble diffidence. Bright yellows against turquoise. Virus patterns on ceramics. It couldn't care less about function… Each piece of furniture offered a plethora of possibilities, options and inconclusive open ends," Bowie wrote of Memphis in a 2002 article in V magazine.

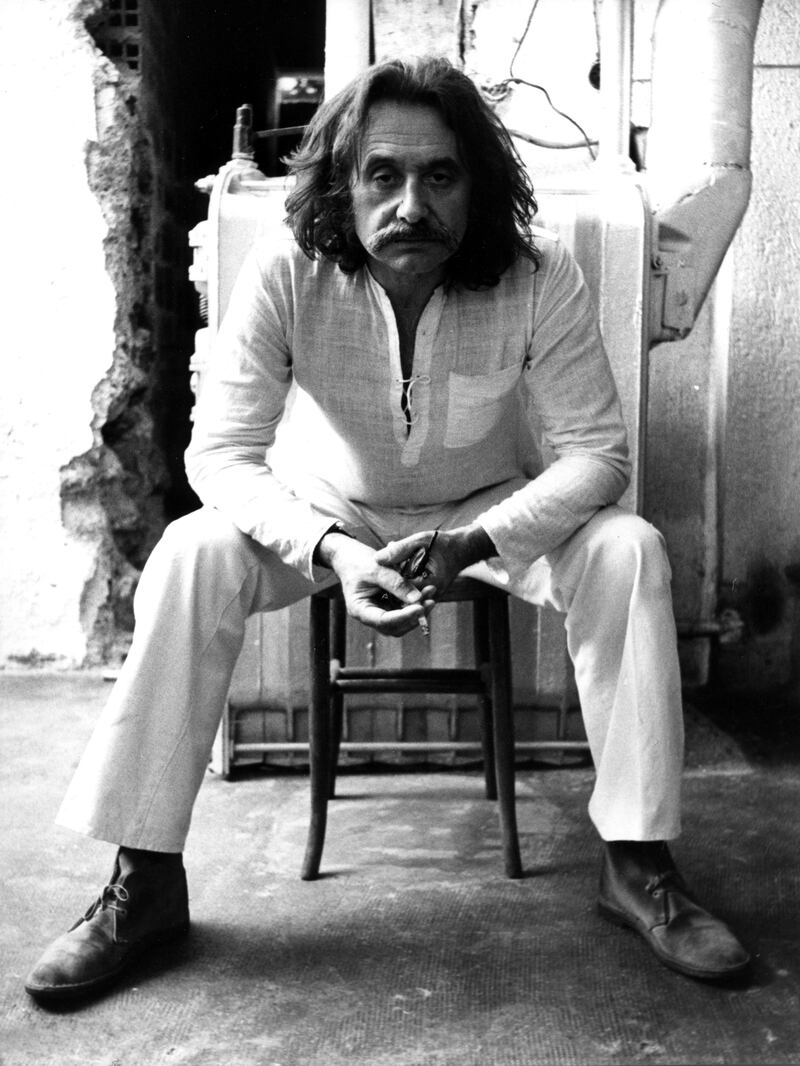

Founded in 1981 by Ettore Sottsass and named after a lyric in a Bob Dylan song, Memphis showed complete disregard for existing definitions of what design should be, casually experimenting with new shapes, materials and patterns.

In Memphis creations, angles appear to defy the laws of physics; stripes, polka dots and animal prints are used with carefree abundance; and contradictory colour combinations reign supreme. More famous incarnations of the Memphis aesthetic include Sottsass's Carlton room divider, a concoction of protruding wood and plastic laminate elements in a palette of yellows, reds, oranges, blues and blacks. The D'Antibes cabinet by George Sowden, meanwhile, is a crazy combination of red doors, patterned yellow sides and slim, elongated legs; and the Brazil table by Peter Shire is essentially a shark in multicoloured table form.

The extent to which Memphis's creative anarchy struck a chord with Bowie became evident after his untimely death last year, when it emerged that he had quietly amassed a collection of more than 100 objects by the design group. His collection, which was put up for sale in a Sotheby's auction in November, showed a particular predilection for works by Memphis's unconventional founder.

In the outlandish, unexpected, unashamedly bold designs of Sottsass, Bowie must have seen an unfettered creativity that he recognised from his own output. "The works produced by the historical avant-garde design collaborative Memphis Milano, led by Ettore Sottsass, could not have found a more receptive and tuned-in audience than David Bowie," said Cécile Verdier, co-head of 20th-century design at Sotheby's, in the run-up to the auction.

"This is design with no limits and no boundaries," she added. "When you look at a piece of Memphis design, you see their unconventionality, the kaleidoscope of forms and patterns, the vibrant contrasting colours that really shouldn't work, but really do."

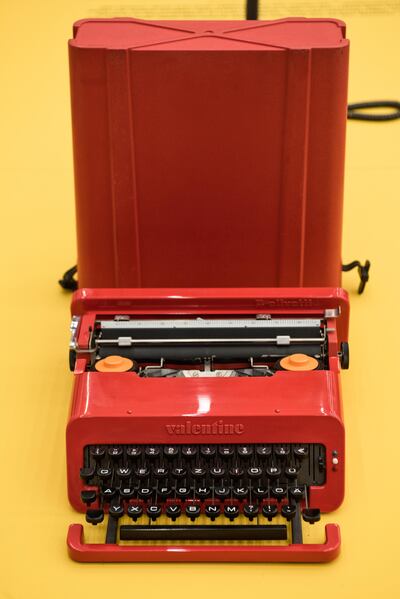

Bowie's extensive Memphis collection started with a lipstick-red typewriter.

Dubbed the Valentine, this is one of Sottsass's best-known creations, emblematic of the era, and now featured in the collections of London's Victoria & Albert Museum and Design Museum, as well as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. By offering an unexpectedly playful reinterpretation of an otherwise mundane object, it is a fitting symbol of Sottsass's aesthetic. Bowie's own Valentine was predicted to sell for between £300 to £500(up to Dh2,385), but ended up fetching a whopping £47,500 at the Sotheby's auction. "The pure gorgeousness of it made me type as much as my need to get the songs down on paper," Bowie wrote of the machine. "I couldn't not look at it." The typewriter led Bowie to Sottsass, who in turn led Bowie to the Memphis Group.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of Sottsass' birth, and 10 years since his death. To mark the occasion, there are two exhibitions currently celebrating his creative prowess. Ettore Sottsass: Design Radical is on at The Metropolitan Museum of Art's Met Breuer in New York, and aims to re-evaluate Sottsass' career by presenting key works across a range of media, including architectural drawings, interiors, furniture, machines, ceramics, glass, jewellery, textiles and pattern, painting and photography.

A second exhibition, Ettore Sottsass. Rebel and Poet, is on at the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, Germany. Running until September 24, this celebration of "one of the most influential and unconventional figures in twentieth-century design" presents an overview of approximately 30 of Sottsass's products, photographs and writings.

Both exhibits act as a reminder of how prolific and versatile Sottsass was. He may be most commonly associated with Memphis, but he was already in his 60s by the time he founded the collective. It was a late move in an already long and illustrious career.

Born in 1917 in Innsbruck, Austria, to Italian-Austrian parents, Sottsass earned a degree in architecture in 1939 from the Politecnico di Torino. He was an unwilling soldier during the Second World War, and spent most of it in a Yugoslavian concentration camp. "There was nothing courageous or enjoyable about the ridiculous war I fought in," he wrote of the experience. "I learned nothing from it."

In 1956, he and his wife, Fernanda Pivano, visited New York and, after a month spent working in the studio of American designer George Nelson, Sottsass was inspired to refocus his efforts on to product design, rather than architecture. He returned to Italy and became a creative consultant for Poltronova, a furniture factory near Florence. By 1958, he had joined the newly created electronics arm of Olivetti, an Italian industrial group, where his award-winning creations included the first Italian electronic calculator and a series of typewriters, including, in 1969, the now famed Valentine. In the late 1970s, Sottsass was part of Studio Alchymia, a group of avant-garde furniture designers including Alessandro Mendini and Andrea Branzi. And in 1981, he formed Memphis, along with Branzi and others such as Michele De Lucchi, George Sowden, Matteo Thun and Nathalie du Pasquier.

"[Functionalism] is not enough. Design should also be sensual and exciting," Sottsass famously said. He carried a camera with him wherever he went, to capture the tiniest of details (reportedly taking 1,780 photographs during one 12-day trip to South America), and recognised that the things he created were not separate to the people who used them, and the context in which they existed. He drew constantly from pop art and beat culture. His work contains no obvious references, but is defined by the broadness of his own experiences – from encounters with the likes of Jack Kerouac, Helmut Newton, Ernest Hemingway and Pablo Picasso, to travels in India, the United States and North Africa.

There is an energy, flamboyance and vitality to his pieces, a sense of freedom, but not frivolity. He was, as the exhibitions maintain, a radical, a poet and a rebel. But most importantly of all, he made it okay for design to be fun.

__________________________

Read more:

Dubai luxury living: How life could look if money were no object

[ When fashion and interiors collide ]

[ Design dilemma: Where to start with technology at home ]

__________________________