Foodies in the UK are increasingly turning to falafel, hummus and kofta to fill their stomachs, according to recent findings by research and consulting companies CGA and AlixPartners. As the country's restaurant sector continues to struggle, several American, Italian and French eateries have closed amid the crisis, but Middle Eastern food has managed to buck the trend.

“The rapid growth of restaurants focused on certain cuisine types highlights how they can quickly find favour in response to the fast-changing tastes of British diners,” says Graeme Smith, managing director of AlixPartners.

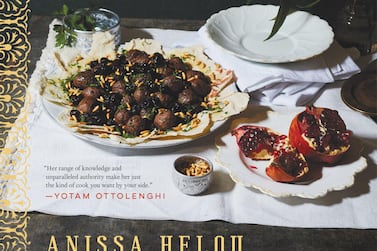

Focused exclusively on restaurants (and not cafes or takeaways), the research found a five-year growth in the number of Middle Eastern restaurants now open – from 60.7 per cent to 270 per cent by June 2019. Independent restaurants outnumber chains by more than five to one, and interest has been turbocharged by a range of cookbooks – from Anissa Helou's Feast: Food of the Islamic World, to the collaborative #BakeForSyria for keen bakers – targeted at the region's food.

Restaurant owners say the cuisine’s ability to suit any taste – from meat-eaters and vegetarians to the health-conscious – is probably behind this popularity. In London’s bustling but ultra-competitive restaurant scene, those in the business report a marked change in preferences.

Healthy food on top

West London, in particular, has long been the heartland for the best places to eat Lebanese food in the capital. Al Waha restaurant in Notting Hill's Westbourne Grove, which has been open for 22 years, has prided itself on serving truly original, authentic Levantine food.

General manager Mohamed Antabli, who is originally from Syria and has been at Al Waha since the beginning, often harks back to the early days when "there was no fuss" from customers over what they would eat. "They would in fact tell you: 'OK, you feed me. What is the best?' So there was a fantastic trust between the clients and us. Gradually this changed quite a lot," he says. "People became more fussy, then we started having these allergy problems, gluten problems, vegans, vegetarians. So you have to deal with all of that as well."

However, the demand for health-conscious meals – as observed by Antabli and alluded to by the CGA and AlixPartners research – seemingly worked to Al Waha's benefit. "I mean, we have 55 starters … We cover the whole lot," says Antabli. "[Once] people started to be more health-aware of what they want to eat, they avoided anything to do with deep-frying for a while and then they started to go for something grilled.

"People are also going for a lot of salads nowadays. We have the cold starters, the tabbouleh, the fattoush, the aubergine salad, the cucumber salad, all these sort of things, healthy stuff. People are asking for it more and more." He notes that diners used to ask for only one salad before moving on to hot starters and main courses, but now the emphasis is often on having four or five salads.

Al Waha served a lot of kofta in the past, but has now made a move towards white meat. It is glaringly apparent, says Antabli, that chicken has replaced lamb as the main meat – typically four times as much chicken is sold as customers go for a less fatty option.

This apparent transition towards better nutrition has also been noticed by Ibrahim Dogus, who owns the Troia Southbank Charcoal Kebab Kitchen, which opened in 2013, and serves Mediterranean and Middle Eastern food. Dogus has seen a "gradual but marked increase" in the popularity of Kurdish and Turkish kebabs, but also dishes with more vegetables, such as imam bayildi, an aubergine-based dish with tomatoes, garlic, peppers and chickpeas.

“It is our mezze options, however, that have become the most popular,” he says. “We see people choosing to mix more traditional mezzes with small European dishes, such as a deep-fried Brie. This perhaps reflects an increasingly adventurous approach to food choices and combinations – as witnessed by the success of fusion restaurants – but also that Turkish, Kurdish and Middle Eastern food is no longer considered something completely foreign, but rather part and parcel of British cuisine.

Vegetarian vote

Another obvious trend is the move towards vegetarian food. Where before diners may have asked for hummus with lamb, they now ask for it with pine nuts instead, and rather than a Levantine pizza with lamb, they choose halloumi on bread.

One of the most popular Middle Eastern restaurants to join the flurry of openings in the past decade was Honey & Co, which opened in London's West End in 2012. The success of its owners, Israeli chefs Itamar Srulovich and Sarit Packer, led to the opening of a grill (Honey & Smoke) and a food shop (Honey & Spice).

The food is "the kind you find in people's homes using the best ingredients we can get our hands on. I think people are more keen to go plant-based, and Middle Eastern food is very, very easy," says Srulovich. "We use a lot of vegetables, a lot of herbs, less meat and all the rich meat sauces. So we've seen a lean towards that, definitely."

Soon after Honey & Co opened, Srulovich and Packer were approached by a number of publishers, who had noticed that people were showing an interest in learning to cook the cuisine. Their cookbook At Home: Middle Eastern Recipes from our Kitchen was published in 2014. "It worked really organically for us at the time because we were at a place with the restaurant where we needed to write down all the recipes and become more structured."

Owing to the focus on fresh produce, the menu is always changing, with favourites such as cheesecake, falafel (with differing seasonings), and freshly baked breads and cakes always on offer. Srulovich believes foodies in the UK capital appreciate his restaurant's consistency and its focus on top-notch meals. "I think diners in London are so open and so varied, and really appreciative of good quality."

Competition on the rise

Of course, with great demand comes great supply – and cut-throat competition. Although the survey found that independent outlets outnumbered group sites by five to one, it still attributed the growth in Middle Eastern food to the opening of some chain restaurants, in particular the Lebanese brand Comptoir Libanais, which has more than 20 sites.

Al Waha's Antabli says the quality has gone down as more restaurants open. He fears the subtleties of Levantine food are being lost as people cut corners, and he believes that only by sticking to authentic ways of preparing food will the best dishes be served. "The quality has gone down enormously without any doubt … they [restaurateurs] come in here and they don't know the difference between a fried kibbeh and a fried falafel.

"When I talk about competition, I'm not just talking about quality and prices, either," he continues. "I'm also talking about it in the sense that if you are living in Hampstead and you've got two or three Lebanese restaurants there, you are not going to travel to me. If you are living in Camden Town, it is just across the road. Before there were fewer restaurants, so people would come from Hampstead, people would come from Wimbledon to eat with you because you are good. But nowadays they don't. Arabic restaurants have popped up everywhere."

Fortunately, supporting Al Waha thus far is a local, non-Arab clientele who eat at the restaurant year-round and ensure it stays afloat. Antabli estimates that 80 per cent of his customers are not from the Arabian Gulf or North Africa. As such, his restaurant does not have to depend on the summer months when people from the Middle East come to visit. "And thank God," he says, "because otherwise we would not be able to survive."