If I tell someone that as part of my job I review restaurants - that essentially I get paid to eat - nine times out of 10 I can predict what comes next. We'll quickly establish that I am very lucky, agree that for many people it's a dream occupation, and then I'll be told that if I'm ever short of a dining partner, I need look no further.

At this point, I often try to interject to venture that while the situation is far from being a woe-is-me one, eating out for work is not the same as doing so for pleasure. I'll sometimes go as far to say that it has its downsides, because the former affects your enjoyment of the latter. This, I've learnt, is not viewed as a particularly convincing argument, but it is true nevertheless.

When you've trained yourself to dissect the restaurant experience, to critique a menu, pay particular attention to the service and assess the presentation, flavour and quality of the food in front of you, it's difficult to switch off. All too often, that internal critic refuses to pipe down and simply enjoy a friend's birthday dinner, instead getting het up about the small (but still consequential) things: a restaurant serving fridge-cold, rock-solid butter with the bread basket, for example.

As the exchange continues, we'll often chew over our favourite restaurants in the region or discuss a recent opening. From time to time, though, the person I'm talking to will tell me - sometimes forcefully - why she (or her husband, mother, dog or boss) disagreed with one of my reviews. This is often accompanied by a certain insinuation - subtle or otherwise - that she could easily do my job, perhaps better than me.

Which, of course, is fair enough. Eating out is a subjective experience, influenced by taste, mood and personal preference. Because we all eat food, everyone can claim to be an expert on it as opposed to the more revered music, art or book critic. One of the benefits of having spent 18 months working 17 hours a day in the kitchen at a Michelin-starred restaurant is that it makes for a decent riposte when I'm asked what on earth makes me think I'm qualified to critique.

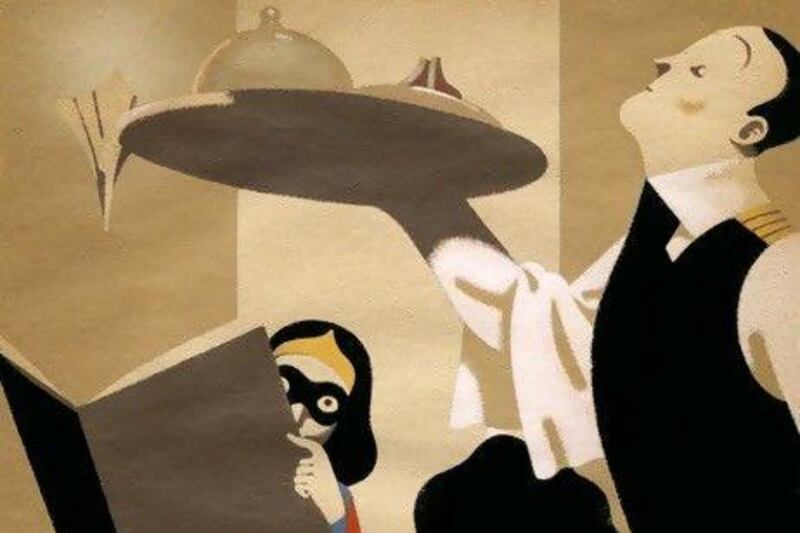

In this job, I believe that integrity is all important. The National is one of the few publications in the region that reviews restaurants anonymously and picks up the bill. It baffles me as to why this isn't common practice. When a meal has been comped, when the chef and the floor staff all know that the person sitting at the table in the corner is reviewing, it makes a difference in how they treat you. As a result, you can't claim that your experience is reflective of that of the average customer.

More to the point, if you've been given a meal gratis, it makes it much harder to be completely honest about the experience. I'm wary about sounding sanctimonious here, but restaurant critics have a responsibility to deliver an entirely honest, considered opinion about the food they've eaten - after all, it might just determine whether a reader decides to visit. It's not about sticking the boot in unnecessarily, of course, but you do have a responsibility to tell the truth.

With this desire to remain anonymous comes the need for a pseudonym. And while it's tempting to be as outlandish and inventive as possible, this rarely pays off. If you're conducting a review, you don't want to draw undue attention to yourself, so unfortunately, cartoon characters and famous actresses are out.

Secondly, and I'm speaking from experience here, if you let your imagination run too far awry, there's always the worry that you'll forget your own name. Let's just say it's confusing for all involved if you're forced to explain that actually your name is Ashley, not Kate, as you first suggested. It's also important to brief your dining companions on your moniker of choice for the evening. I once arrived late to a restaurant that I wanted to review, only to find my friend insisting that the manager recheck the reservations book, loudly proffering my real name as she did so.

And while we're on the subject of dining partners, the restaurant critic must pick his or hers wisely. The chatterbox who becomes monosyllabic when it comes to discussing food ("Yeah, it's all right") has no use here, nor does the greedy eater who refuses to let you taste her dish. Meanwhile, the fussy friend who wants to order entirely off piste, or stick to the same dish week in and week out, is also best avoided.

My fiancé is the head chef of a restaurant in Dubai and therefore he knows some of the other chefs working in the region. It's important, then, that we determine whether he's likely to be recognised before he accompanies me on a review.

We've almost been rumbled a couple of times, but I learnt my lesson a year or so back when we visited one of Dubai's high-end Italian restaurants. Initially, I thought nothing of the fact that the kitchen was open plan. It was only when a middle course of white truffle-dusted risotto winged its way to our table, followed by a grinning chef we both knew from our days back in London, that I clicked, put my notebook (iPhone) away for the night and resigned myself to the fact that this meal would not be going on expenses.

While I enjoy eating out, I do have a few pet peeves. One of them is restaurants that insist on turning the tables (ie, offering two seatings, the first of which is often irritatingly early, the second too late). If the place really is that busy, then fair enough. However, it grieves me if after being told several times that the table needs to be vacated at a certain time to make room for the next wave of customers, you rush through dessert only to realise that the place is pretty much empty.

There's no denying that service impacts upon our enjoyment of a meal. While no one likes to feel ignored, and insouciance, arrogance and lack of knowledge can quickly raise hackles, it's over-attentiveness that winds me up the most. Even writing that I feel slightly guilty; this is a mistake born out of good intentions, after all. Nevertheless, when I leave a restaurant feeling as if I've spent more time exchanging pleasantries with the front-of-house staff than my dining companion, it doesn't feel right.

On occasion, I have experienced waiters standing right next to me, poised to refill my water glass even before I've raised it to my lips; had plates removed and replaced midway through a main course without comment or explanation; and, bizarrely, watched a waiter take every item off our table, including the tablecloth, before methodically replacing them. On this occasion, intrigue got the better of me, and I asked what he was doing. Apparently either my friend or I had unknowingly dropped a spot of oil on the tablecloth and the waiter believed we couldn't possibly continue to enjoy our meal until the offending mark was banished from sight.

Eating at an old-school, three-Michelin-starred restaurant a few years back - where reverence rather than conviviality was the mood du jour - I watched a look of abject horror cross the face of a waiter as he realised that my dining partner was about to return to the table after going to the bathroom without his white linen napkin having been removed and replaced. He threw himself across the room and initiated the swap in the nick of time, while simultaneously pulling out my companion's chair to allow him to sit down.

I have been writing about restaurants in the UAE for almost two years now. Looking back, the first restaurant I visited here with the intention of reviewing was also the worst. I'd read about a place where rather than having a fixed menu, the chef designed a dinner based on your likes and dislikes and what was fresh on the day. These days, the cynic in me would point out that what this does is allow the kitchen to keep the food costs low, by repackaging leftovers and keeping outlay to a minimum; what's to stop them from serving the same "bespoke" menu to every single person in the restaurant that evening?

Unfortunately for us (and them), we were the only customers that night, which - along with the fact that as we arrived we bumped into the manager having a not-so crafty cigarette outside the front door - proved to be a sign that all was not as it should be.

What followed was an evening of interminable length: course after course of fussily presented food, which tasted mediocre at best and cost an extortionate sum. When our waiter revealed that in his opinion the restaurant should have closed down months ago, we took it as a sign to leave. To cap it all, I misplaced the receipt on the way home, so ended up paying for the experience myself. Lesson well learnt.

Happily though, this was a one off, and while I do think there is a way to go until the UAE's dining scene can rival the likes of those in London, Paris and New York, things are certainly moving in the right direction.

Winning the battle of the bulge

I've come to the conclusion that people expect food critics to be overweight. Now, if I accepted every offer that I receive from kind public relations people inviting me to sample a restaurant's new menu or attend a seven-course themed lunch, then I imagine I would be packing a few extra pounds. I'd also probably be out of a job, given that all that eating takes up valuable time when you should be writing articles.

My point being that despite what people might think, I don't eat out every night and when I'm at home, I cook healthy food.

When you're going out for dinner in the evening, I've learnt that it's important to eat well during the day. If you arrive at a restaurant feeling ravenously hungry, you'll end up paying undue attention to the bread basket. The smell of a freshly baked loaf makes my mouth water as much as the next person's, but I'm not hugely keen on eating it as a precursor to dinner. Bread is stodgy and therefore guaranteed to fill you up, so I don't quite understand the logic of eating a couple of slices while waiting for the starters to arrive.

While I'm very much against wasting food, I am quite aware of stopping eating once I'm full; a plate doesn't have to be empty just to prove that you've enjoyed it. A few years ago, I was working on a television show with Prue Leith, founder of Leiths School of Food and Wine in west London and one of the doyennes of the British culinary scene. She said that whenever she eats something that she knows isn't particularly healthy, she asks herself if it's worth the calories. So, for example, eating a bowl of pale, soggy, uninteresting, under-seasoned French fries would be seen as a waste of calories, but rounding off a meal with a wedge of rich, buttery Brie is entirely worth it (if you're a cheese lover, of course).

It's a simple but efficient premise and one that has stopped me from polishing off many a mediocre chocolate mousse.