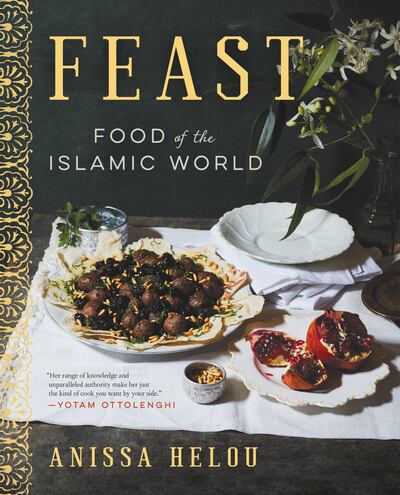

"Islam was born at the beginning of the seventh century in one of the world's harshest climates," begins Anissa Helou's 544-page cookbook, Feast: Food of the Islamic World. The half-Lebanese, half-Syrian writer is referring to seventh-century Makkah, but it was a different kind of harsh climate that led her to take on this epic project.

“It was really a response to the vilification of Muslims that started with 9/11,” she explains, by phone from Lebanon. “I wanted to show that there’s a very rich history to Islamic civilisation, great cuisines – a lot more than terrorism and fanaticism.”

Covering thousands of miles from North Africa to South Asia, as well as fringe countries such as Nigeria, Malaysia and Indonesia, the sheer scope of the book would have left most authors floundering. But Helou, a former art dealer whose first cookbook, Lebanese Cuisine, was published in the 1990s, hit upon the idea of splitting her vast subject matter into ingredient categories, beginning with the staples of bread and rice, and adding in others such as spices, meat and fish.

“Bread and kebabs are probably the most universal elements across the Islamic world,” she says. “Even though Indonesia is not a country of bread, there are breads there. And in China, the Muslim community is where you find bread, and the noodles are made out of wheat.”

What interested Helou was the endless diversity within these loose themes. “One thing I’ve been fascinated by is the multilayered breads. There are endless techniques and variations, whether it’s paratha in India or a similar thing I had recently in Kyrgyzstan.”

Spices seemed to have blown around the different corners of the region, with saffron popular in North Africa, saffron and cardamom favoured in the Gulf countries, and slightly less cardamom used with dried lime in Iran. “Each of the countries has its own spice mixture or spices that you could say they are almost universally used,” she says, citing as an example the seven-spice mixtures of Lebanon and Syria.

She also enthuses about rice and biryanis, in particular the UAE versions that caused her to gain a “Dubai stone” while filming a TV show in the emirate a few years ago. “They [Emiratis] really have a way with rice,” she says. “Different ways of cooking it, but in all the different dishes it’s fluffy, long-grain, and very tasty because they use a lot of spices. I think I went home about three or four kilos heavier.”

It was another UAE speciality, however, that made headlines when Feast was first published earlier this year: the camel hump. This had been an obsession of Helou's for some years. "I was genuinely excited to try it. I had tried camel before and never thought it was very good, but the camel hump was mythical in a way," she says.

Eventually, she was able to try the meat in a catering kitchen (“I didn’t think it was amazing but I’d got my taste”), but finally understood what the dish was meant to be when a friend gave her a whole camel from a market in Sharjah. It was young – “You have to get a really small camel, milk-fed,” she advises – and she chose to cook it in the traditional way, rubbing rosewater, saffron and bezar – an Emirati spice blend that includes cloves, cardomom, black peppercorns and cinnamon – into the flesh before roasting it in the oven until “crisp and golden”.

The author insists that the very best food is always to be found in homes. “Almost every single Lebanese person is going to tell you that their mother makes the dish you’ve just given them better than you’ve just made it,” she says. And apparently this is not a matter of bias. “In the Arab world, restaurants cater to a lot of people and they cook the same menu day in, day out. Whereas the women at home are totally passionate and they’re never going to cook for more than 12 or 20 people at the most. Home cooking is much more refined, there’s much more attention to detail in how you pick foods, vegetables, meat …”

The idea of cooking as a family tradition is at the heart of Feast, not just in the stories, but the sense that recipes are being passed down before they are forgotten by a new generation – or worse, destroyed, as in Syria. "I covered Syria from before the war," Helou says ruefully. "I wish I had written a book about Syrian food. But I knew the food, knew the people I could talk to whom I had known from before the war, and I used to do culinary tours there, so I didn't have to go back to write Feast."

In her view, the country will never recover its culinary heritage entirely; even Damascus has lost too much. “What will happen to these producers who were making wonderful clotted cream or cheese?” she asks. “All this will be lost. Even if they moved their business to somewhere else, it’s not going to be quite the same.”

Nonetheless, it is to be welcomed that the displaced are bringing their food culture to new homes such as Canada. Helou’s main focus is on preserving culinary traditions for future generations, but she is also interested in how they can be interpreted by the diaspora.

“I remember once at a Lebanese restaurant in Sao Paolo, I had shish barak, little dumplings cooked in yoghurt. You would rarely find that in a restaurant in Lebanon; it’s mainly a home-cooked dish, but it seemed normal to have it on a menu in Sao Paolo,” she says.

As a cookery teacher in London, she has also been struck by how strong the culture of food is among Muslims, even those who no longer speak Arabic. “I always have Arab-Americans who come when I’m teaching, and sometimes the only Arab thing about them is their love for the food. Some of them haven’t even visited the Islamic world, but they’ve eaten [the cuisine] at their mother’s or grandmother’s. The memory of the food, and the food itself, is sacrosanct.”

Is it a worry that as people begin to enjoy more opportunities at work, the old ways of cooking will be lost? “The young ones are not so keen on cooking and that could be a problem later, with the recipes being forgotten,” says Helou. “But of the women who are working, most of them will still cook traditional food, they will just find ways of not spending so much time in the kitchen. Like in Damascus, they have the souk of the lazy people where you have a whole army of women shopping pre-prepared chopped parsley, or courgettes and aubergines already cored for their stuffed vegetables … Or in Indonesia there’s a lot more ready-made food, but it’s made very traditionally and usually by people at home,” she explains.

Of course, some cultures make more of their cuisines than others, and the author draws a distinction between the cuisines that amused her – the “fun” dishes of Zanzibar and the novelty of eating rice for breakfast, lunch and dinner in Indonesia – and the more effortful versions found in Morocco, Iran and Turkey, whose offerings she finds “exquisite”. In the UAE, she saw a slightly more limited repertoire, “but what they have is excellent.

You could see the influences from Iran and India. They’ve adapted the recipes and made them their own.” Helou speaks with humour and humanity, and it’s easy to see how she succeeded in engaging with communities everywhere she travelled while researching the book – using translators and even sign language to communicate with people in the markets of countries beyond the reach of her Arabic, such as China and Uzbekistan.

As Helou suspected, a love of food translates into any language, and this certainly comes across in her book. It feels like a lifetime achievement for this extraordinary writer – even if not everyone was impressed. “When I gave it to my mother, she said: ‘Why did you write such a big book?’ because it’s so heavy.”

You can’t win them all.

________________________

Read more:

Breaking bread in conflict with Yasmin Khan

Cook sushi rice right, every time, and try these two tasty recipes

Why the allure of Dubai's Big Bad Wolf book sale is too great to resist

________________________