Kala was born in Kathmandu. Kala is Nepalese. But, as all of her blood relatives abandoned her when she was young, she has no birth certificate, meaning she is undocumented and therefore not legally recognised as a citizen in her own home country.

It all began when she was less than a year old. Kala's mother, struggling to make ends meet, travelled from Nepal to find work in Dubai. Not long after, Kala's father remarried and moved away to a remote Nepalese village, leaving the little girl in the care of her grandmother. While Kala's mother sent money back home from the UAE to support her, Kala lived a miserable life, as both her adopted brother and grandmother beat her on a regular basis. Once, when she was 12, she was beaten so badly she left home and slept in an empty car park in one of the nearby slums.

Soon afterwards, a neighbour agreed to allow Kala to stay with them, as long as she helped out with household chores and childcare. Before long, however, her grandmother moved away, leaving Kala in a city with no family. No one registered her birth and no one was willing or able to help her do so as she got older.

A global problem

There are an estimated 5.5 million children in Nepal in a similar situation to Kala; roughly 48 per cent of the under-18 population have no official identification documents. While having a name and nationality is every child's birthright, as enshrined in the Convention on the Rights of the Child and other international treaties, about 25 per cent of children under the age of 5 worldwide have never been registered, a 2017 Unicef report says. "Registering children at birth is the first step in securing their recognition before the law, safeguarding their rights and ensuring that any violation of these rights does not go unnoticed," the organisation states.

It's more than simply an issue of identity. Without birth registration, children are vulnerable. It means they have few or no rights. In Nepal, unregistered children only have access to basic health care and struggle to receive a proper education. In 2015, the Nepalese government said every child required birth registration documents to join formal schooling. This leaves girls such as Kala further exposed to exploitation, particularly as the border between Nepal and India is one of the busiest human-trafficking routes in the world. About 12,000 children, mostly female, are trafficked to India from Nepal every year, according to Unicef. Most are destined for brothels and some are forced into bonded labour or marriage.

The problem, perhaps unsurprisingly, is exacerbated by poverty. Across South Asia, 78 per cent of children in the richest sector are registered, compared with only 45 per cent from the poorest families. Studies show that, as more high-income families record births, so too do people from lower-income families.

The Bridge by SathSath

While the onus is on everyone to make a change, one group fighting against this kind of exploitation is SathSath, a Kathmandu-based NGO that works with disadvantaged and underprivileged children and their families across Nepal. It runs a programme called The Bridge, which helps young people re-enter the formal educational system, while the team also offers counselling. Ultimately, they help them get off the streets and regain a sense of hope and self-confidence. "These children are not living on the street out of choice," says Biso Bajracharya, the charity's executive director. "They are victims of circumstance and they are missing out on the basic right to education. We are advocating strongly to solve the problem and working with the government to facilitate an easier process."

One way they are doing this is through a project launched this month in collaboration with UK-based charity Toybox, which addresses the issue of birth registration. Nepalese law dictates that children must return to the place in which they were born or where their parents are from to register their birth, explains Al Richardson, international programmes director at Toybox. But most children who live on the streets come from families in remote rural villages. A journey "home" could take days or even weeks and would be prohibitively expensive.

"Work is vital to provide basic daily food for themselves and their families, so they can't just take that time away to travel to the family home," says Richardson. "Children also often need documentation of their parents' birth, but their parents may not have been registered, meaning no such documentation exists."

'They now have hope for the future'

It is a vicious cycle that only becomes more difficult as time goes on, with families losing records and administrative fees increasing as the child grows older. The average cost of basic registration paperwork is Dhs164, although given that children must travel long distances to return to their village or employ lawyers to help to prove their legal rights to property and inheritance, costs increase significantly.

Individual situations become even more complicated when there are toxic family dynamics to deal with, Bajracharya adds. "It is often the case that the extended family of orphaned or abandoned children don't want to recognise their relationship to the children because that means they [the children] will have the right to claim property and other assets."

Take Prim, for example, who was only 9 years old when she was forced to leave home with her two brothers after their father died and their mother abandoned them. Prim's uncle had moved into the family home and abused her and her siblings so badly they were left with no other choice but to leave. As the children were not registered, they had no rights to the high-value property, which was in the thriving central business district of Kathmandu.

Instead, Prim and her brothers had to live on the streets, which is illegal in Nepal. They struggled to survive, begging and collecting rubbish during the day and, at night, sleeping huddled together under newspapers, doing their best to avoid the police. That was until SathSath representatives found the children in a Hindu temple complex about five kilometres outside Kathmandu, where the organisation regularly hosts an education project.

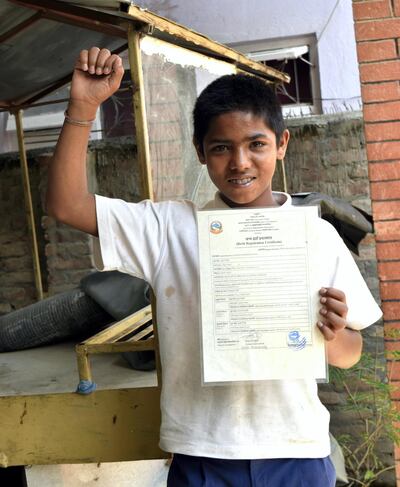

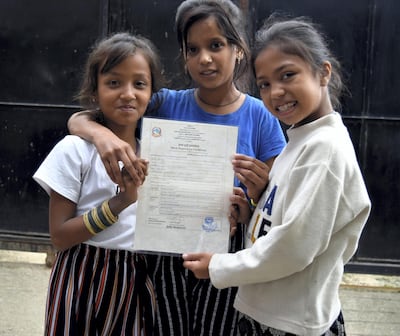

Slowly but surely, the charity workers got to know Prim and her brothers, familiarising themselves with their story and helping them to reconnect with their uncle. They soon managed to persuade him into testifying that they were his niece and nephews, which meant the children could receive their birth certificates.

For the first time in their lives, the trio were recognised as legal citizens of Nepal and were able to move back into the house their parents had owned, without their abusive uncle, as well as enrol in school. "It is difficult to put into words the positive impact these documents had on these children's lives," says Bajracharya. "They now have hope for the future, they can study, they can get a job and can have families of their own."

'I have to do whatever I can to help'

Many of us take having a birth certificate, a passport and an official nationality for granted, not realising how many benefits these documents bring with them, Richardson says. "To gain quality employment, employees often require formal identification and without this young people are trapped in a cycle of working in the informal sector and poverty," she says. "Without identification, a person is unable to vote or have a say in issues that affect where they live or how they are treated. Many teenagers without birth registration have no way of proving how old they are and, as a result, are often treated as adults by the judiciary system. Having access to services and opportunities is vital, but having a birth certificate gives more than only that – it gives a person an identity and a sense of worth and belonging."

In the next two-and-a-half years, Toybox and SathSath aim to register 230 of Nepal's most vulnerable children. "We are aware that there are many more children in need of our support and we are continuing to explore funding opportunities to continue this programming," Richardson says. "As this is the first time that Toybox has worked on issues of birth registration in Nepal, we will learn a lot through the project, improving our approach for the greatest impact."

While Toybox is new to Nepal, the charity, whose end goal is to stop all children from being forced to live on the street anywhere, has already helped 5,500 children in Guatemala, El Salvador and Bolivia to get their registration documents.

It might seem like a drop in the ocean, but every journey starts with a single step. "We have a social and human responsibility to help vulnerable people and especially children," says Bajracharya. "If we don't take responsibility for them, then who will? Personally, I cannot simply sit back and watch them suffer. I have to do whatever I can to help."

More information is available at toybox.org.uk and sathsath.org