Fur, diamonds and immaculately coiffed hair stretch as far as the eye can see. In the spectacular Santa Spirito in Sassia venue situated within the walls of the Vatican City, the large audience coos at the elaborate creations sashaying down the runway, mothers and daughters contemplating the fairy-tale wedding dresses on display. Meanwhile, down the road, hip Italian tastemakers join the blogging supremos Diane Pernet and Scott Schuman to thumb through avant-garde magazines at a festival of independent fashion publishing. The two events might seem about as far apart as you get on the fashion spectrum, but both were taking place as part of Rome's spring couture week, AltaRomAltaModa, a few weeks ago. Despite raising fashion stock of international calibre - Valentino, Gucci's Frida Giannini and the house of Fendi to name a few - the Italian couture capital seems to be suffering something of an identity crisis. And even fellow Italians have put the boot in: earlier this month, Giorgio Armani complained to the Italian media that Rome "has killed high fashion by showcasing people who didn't merit it".

Where Paris is France's fashion capital lock, stock and barrel, the Italians do things differently. Milan is the undisputed centre of ready-to-wear, Florence claims menswear and Rome has couture. But where the theatrics of Paris couture are more likely to sell a brand's perfume than the clothes on the runway, Rome's haute fashion remains its bread and butter. The cutting, fabric and painstaking workmanship are exquisite, but the industry that once dressed screen idols and boasted Valentino on its runways is struggling to compete with the pace and price of prêt-a-porter in Milan and beyond. Nicoletta Fiorucci, the president of Rome's fashion body Alta Roma, believes that the changing attitudes towards fashion, rather than the current economic woes, are to blame. "The changes in lifestyles have been crucial in the change of the approach and attitude of people towards fashion," she says. "Until the 1960s or 1970s, people would change for the evening. The couture client today either lives a very high lifestyle or addresses this field only on special occasions."

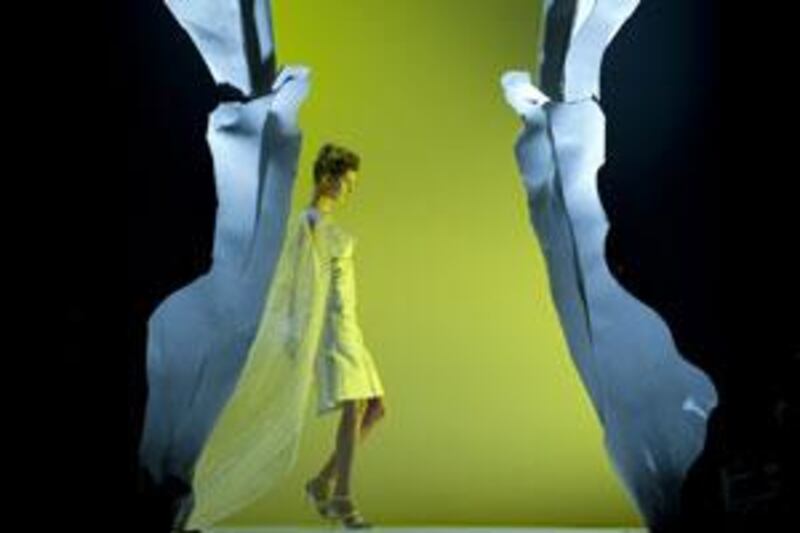

But Fiorucci is ringing the changes. She concedes that Armani's jibes hold true of past fashion weeks, but says the schedule was slicker this time around, with a focus on the best of the old and new. "The only way to get important names to come back to show in Rome is by presenting them with an impeccable event in terms of design, quality and glamour," she says. Also reviving Rome's fashion week are some new international names that give audiences a different perspective on couture dressing and help ditch the "locals only" reputation that Rome fashion currently carries. This season, for example, Rome's wealthy were able to ponder creations by the Dubai-based Syrian couturier Rami al Ali, whose floor-length concoctions injected some eastern glamour into proceedings.

But Rome's fashion industry isn't just about evening gowns: it's also a place where new design talent can thrive. The city's annual Who's on Next competition with Vogue Italia is judged by fashion luminaries including Franca Sozzani, André Leon Talley and Harvey Nichols' London buying director, Averyl Oates. Its ability to unearth the next big thing is uncanny, with past victors including Nicholas Kirkwood and 6267. Last year's winner, Gabriele Colangelo, believes that Rome's fashion week presents opportunities for new designers to make their mark outside of the fashion pecking order: "I think it's a place where a young talent can present his work without suffering from the buzz and attention that the system only creates around the big names."

In order to keep this tradition of supporting new talent, it's essential to preserve the skills of the old masters, says Ilaria Fendi, who as part of the Fendi dynasty has grown up in a family that has shaped Rome's fashion history. Fendi works with Rome's artisans to sell ethical accessories, made from recycled materials, and is concerned that they are threatened by the global fashion industry. "Rome still has a much-envied tradition of tailoring, of boutiques and artisans that survive even though they are threatened by globalisation - this is its richness, and its weakening would be a loss for everybody. We would lose skills that, once gone, would be hard to recover."

The French designer Pascal Gautrand agrees. He thinks that using these skills is crucial to not just the future of Rome, but the future of luxury fashion in a time when the consumer seems to be tiring of the "me too" brand culture. "The system is interesting because it offers the opportunity of production outside of the ready-to-wear system," he says. Gautrand showed an exhibition during fashion week that used Rome's specialist artisan techniques for the 21st century. Titled When in Rome? it takes a mass-produced shirt from Zara as its starting point and shows it re-created by 30 of Rome's couturiers. Exhibited side by side, the craftsmanship and detail in each shirt is astounding and the pieces retail at between ?60 (Dh278) and ?500 (Dh2,325). The project is about re-engaging customers with the traditions and skills that create their clothes - and Gautrand believes this is part of a new attitude to luxury dressing.

With this is mind, maybe Fiorucci's pick-and-mix attitude to Rome's fashion past and future is on the right track after all. Rome's couture won't die if it learns to evolve, and even bastions of the Rome scene agree that change is good. "If we continue to feel ourselves as victims instead of finding new proposals, nothing can be done to solve the situation," says the couture legend Renato Balestra. A hand-beaded evening gown might not be within everyone's budget, but investing in a unique, made-to-measure shirt or impeccably cut little black dress suddenly seems more luxurious than carrying the latest It-bag on your arm. "Nowadays, real luxury is being identified with craftsmanship," says Fendi. She has a point. Perhaps it's not Rome's idea of luxury that's being left behind. Perhaps we're only just catching up.