Can you name a famous Danish television actress? Chances are, probably not. A woman who looks, to a Dane, like a television superstar, to you looks like no one -special.

The fact that you can’t name a single famous Danish television star is symptomatic of one aspect of the way television has always worked. In short, it has worked like this: television is siloed by nation, so that the viewing public of each country watches its own television and has its own television stars.

The exception, of course, is the US. North American television stars often get famous everywhere because stations around the world buy US shows through syndication and no one thinks that is unusual. That in itself is an interesting sign of the way American culture conquered the world in the second half of the 20th century, but let’s not digress.

For other countries, television programmes almost always stay in the country they were born in. That made television a unique window on to the culture and communal consciousness of a country. Want to get underneath the skin of the British or the Italian or the South Korean? You could do far worse than starting with their television shows.

Now, all this is changing. In place of a national television culture, we’re seeing the rise of a television culture that knows no boundaries. We’re amid the rise of global television.

This is a cultural trend but, as is so often the case, it's underpinned by technological change. Online content platforms mean the biggest television events aren't necessarily country-specific; rather, they're global phenomena. The DVD rental and content streaming service Netflix is perhaps the most-talked-about example. It made headlines recently when it moved into making drama: its original series House of Cards, based on a television series first shown in the UK in 1990 and starring Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright, drew headlines around the world.

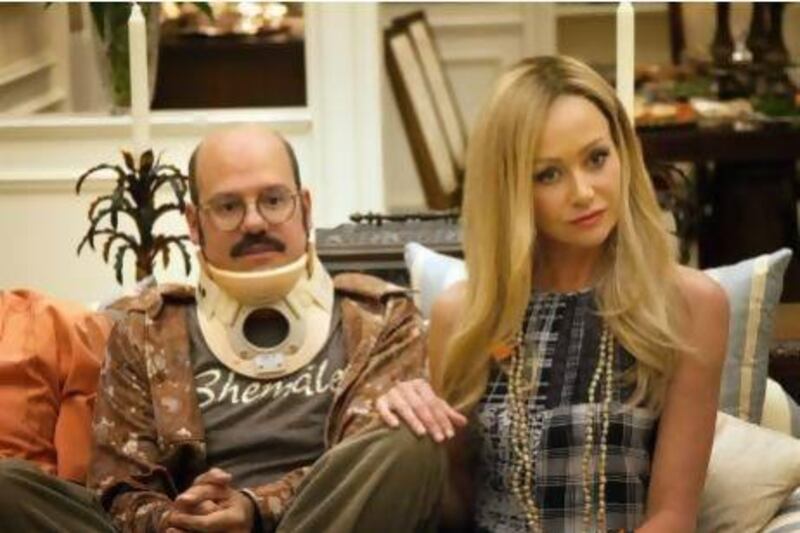

Netflix has also resurrected the hit comedy Arrested Development – brand new episodes are now being devoured by a global audience.

And now, start-ups such as DramaFever.com and Viki.com are pushing globalised television further, bringing drama from across the planet – Korea to Nigeria to the Middle East – to a global audience. Viki.com, for example, presents content from around the world and even crowdsources subtitling of that content out to its community of viewers. Fancy a few episodes of the Korean hit sitcom Panda and Hedgehog? Viki.com has 37 of them.

Expect a world, then, in which television becomes less about national culture (with a dose of the US), and more about the global brain. And that, of course, is because television is no longer delivered via televisions, instead it’s delivered via online space. Traditional national television stations will have to adjust; who’ll want to watch another episode of their crummy 9pm drama when there is Panda and Hedgehog available in an instant? And a new generation of truly global television stars will soon be with us.

By the way, for a Danish actress you could have said Sofie Gråbøl, the star of the Danish drama The Killing. That show became a hit on British television in 2011 after first being broadcast in Denmark in 2007 – one of the early signs of the emergence of a global television culture.

David Mattin is the lead strategist at trendwatching.com

For more trends, go to https://www.thenationalnews.com/trends

Follow us

[ @LifeNationalUAE ]

Follow us on Facebook for discussions, entertainment, reviews, wellness and news.