The posters greet you as soon as you land at Bogota's international airport, depicting a glorious, verdant forest. But it is their tagline that leaves a lingering impression: "Colombia, the only risk is wanting to stay".

It is a tacit acknowledgement from the country's own tourist board that while foreign visitors are starting to trickle into this relatively undiscovered corner of Latin America, it has long been a no-go zone, thanks to its appalling reputation for drugs and violence.

Colombia's history has been shaped by decades of armed conflict, stark social injustice, class divide and extreme poverty. The social equality once envisioned by El Libertador Simón Bolivar quickly disintegrated soon after he freed his nation from its Spanish invaders two centuries ago and has never been reclaimed since.

Instead, the last 50 years have witnessed the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of innocent victims, caught in the crossfire between rebel leftist guerrilla groups such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the National Liberation Army (ELN) and M-19, and right-wing paramilitary armies.

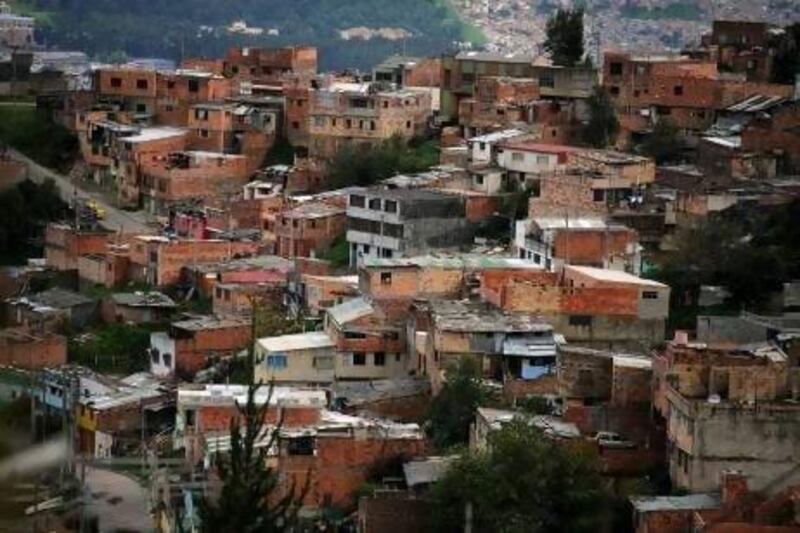

An estimated 3.5 million Colombians have been displaced over the years, particularly from the rural regions where rebels have their strongholds and the roots of lawlessness run deep in this undeclared civil war. They are driven into the slums that sprawl ever-upwards into the mountains surrounding the cities.

And while the all-powerful drug cartels of the 1980s and 1990s have been disbanded, it is still narco-traffic filling the coffers of armed guerrillas to this day, despite concerted efforts from the government and millions of dollars of US cash pumped into the country to combat drug production and trafficking.

This is a country rich in natural resources with booming industries of oil, coal, gold and emerald mining, while coffee, flowers, coca and bananas are among the most lucrative exports. Yet 10 per cent of the population commands 80 per cent of the country's wealth.

Even during the boom years of former president Alvaro Uribe, unemployment stood at 12 per cent. As Tom Feiling writes in Short Walks from Bogota, the nation has "first, second and third worlds living side by side".

Today the victims of that inequality are all too evident on the streets of every city, from Bogota to Medellin and Cartagena. They are Colombia's street children, raised in the gutter and fighting the circumstances of birth and deprivation to eke out a living.

With the odds stacked against them, their extraordinary resilience ensures their survival. But those charged with protecting them, having watched helplessly as micro drug cartels have risen in strength and influence, fear an increase in exploitation and abuse.

"Walk faster," hisses Salome Lopez Pena. It is 5pm in Bogota's red light district, but even as a native Colombian, she is deeply fearful in one of her city's most notorious neighbourhoods.

I have been forbidden from speaking in case my foreign accent makes us targets. My nervous guide constantly checks over her shoulder. Even locals refrain from walking here.

The main artery of Caracas Avenue runs through this district, bisected by numbered roads. The streets are starting to fill with prostitutes and drug dealers, even though it is still daylight.

Policemen standing a few yards away do nothing. This is the tolerance zone, where vices are legitimised under the guise of being policed by the state. It means the authorities also turn a blind eye to the vulnerable.

The youthful faces of teenage girls are among the throngs of women doing a brisk trade. Two dressed in denim slips have smeared their faces in garish make-up with all the amateurishness of 13-year-olds. Another, who is younger still and heavily under the influence of some unknown substance, slumps against a shop wall.

"They start at six or seven years old," sighs Martha Cardenas, who co-founded Fundacion Renacer - the Rebirth Foundation - with her sister Luz Stella in 1988.

The pair were volunteering with a church group helping children involved in prostitution and decided to set up a permanent organisation helping youngsters at risk.

While the government's family welfare department, Bienestar Familiar, offers funding for externally-run programmes and works in partnership with them, it does not manage any of its own.

So, the Cardenas sisters, who care for 400 children in two centres, have their work cut out.

"We work with children who have been exploited or are at risk of exploitation. Usually it is friends of the parents who put them in that environment and force them to work," says Cardenas. "Most of them have families but live on the street. We believe it is getting worse because more cases are coming in and they are getting younger."

Children end up on the streets because of a number of factors, whether they have been orphaned, sexually or physically abused by someone at home, poverty or because they have been put to work by their parents.

In a society where single and teenage mothers are rife, parents living on the breadline become trapped in a cycle of deprivation. In desperation, they put their children to work.

From necessity, Fundacion Renacer's day centre is in the heart of one of the bleakest neighbourhoods. Barrio Samper Mendoza runs alongside a dried-up riverbed choked under mountains of rubbish. An unbearable stench rises up as filthy children, men and women dressed in rags pick over the discarded heap for coal and plastic to recycle. It is a shocking scene of almost Dickensian poverty.

But more heartbreaking still is the scene inside the day school. Youngsters from five upwards sit chanting algebraic equations, reading or playing. While the classrooms may resemble any other, the inescapable reality is that these children will return to lives of hardship at the end of each day.

Three teenagers are pregnant. Two sisters aged nine and 10 will return to the hostel where they were molested by a man because their mother cares little for their well-being. And one five-year-old boy is only dressed and fed because his older brother, himself a child, cares for him. With his mother working the streets and his father abandoning his duties, it is a miracle he is here and learning.

Psychologist Rocio Villamil says: "Some are the sons and daughters of prostitutes and for them, it is normal. That is the environment they live in. They know if they need money they can exchange their bodies. To them, it is a transaction.

"At least here they get love and understanding and are allowed to express their emotions."

Engineer Jaime Jaramillo was on an oilfield exploration job when, from the window of his helicopter, he spotted something glinting below. He ordered the pilot to land and discovered Claudia, a 10-year-old with Down's syndrome, struggling up a mountainside with a tank of boiling water strapped to her scalded back. She cowered like an animal when he approached her.

Her parents, ignorant about her condition, had labelled her a "daughter of the devil" and were using her as a human mule. Jaramillo airlifted her from that life of hell and took her under his wing. Today she is a contented 33-year-old with her own room at one of the five homes funded by Jaramillo's charity, Fundacion Ninos de los Andes, or Children of the Andes.

Jaramillo, 56, admits his methods might be unorthodox - but they get results.

"I go by divine rules," he says. "Human laws are very flawed. My mission and my law are what my heart feels."

It was his cavalier attitude to his own safety that led him to discover one of the horrifying fallouts of armed conflict.

In the 1980s shopkeepers, restaurant owners and police were conspiring to keep street children from ruining their businesses and were paying death squads to obliterate them from public view, earning them the name los depechables (the disposables.)

Jaramillo followed one child and discovered an entire community of youngsters living in the network of sewers under Bogota. There among the stench and filth, they were leading a precarious existence on slippery ledges, risking disease and, on occasion, incineration by petrol bombs tossed into the sewers by the death squads.

He began making regular trips into the sewers wearing diving gear as protection, persuading its vulnerable but defiant inhabitants to emerge and take shelter in one of his homes.

His foundation, which began with a modest home for 25 boys and girls in 1984, has had 65,000 children pass through its doors to date. Not all have made it.

His ex-wife Patricia Gonzales, a director at the charity, says they have a 40 per cent success rate: "We have a lot of success stories but not all the children are able to better themselves. Some are beyond help or do not want it," she says. "Living on the streets is a culture and a way of life."

Medellin, the City of Eternal Spring, is known for many things, including its fashion, its parks and its striking architecture.

It is also known for being the birthplace of Pablo Escobar, the notorious head of the Medellin cartel responsible for 80 per cent of cocaine traffic to the United States before he was gunned down in 1993.

Escobar's narco dollars built shopping malls, schools, hospitals and discos. They funded a lavish lifestyle, which meant he was heralded as a hero of the common people as well as making him the seventh-richest man in the world in 1989, according to Forbes magazine. It also turned Medellin into the murder capital of the world, as his cartel killed at random to maintain power.

Those cartels might now have dissipated, but Colombia's drug problems are far from over.

Only last week, as the Colombian cocaine trafficker Daniel Barrera was arrested, questions were being asked about how he evaded capture for so long.

Part of a second generation of traffickers, he struck deals with both FARC and the paramilitaries to operate without interference. It seems president Juan Manuel Santos' declaration that "the last of the great capos has fallen" may have come prematurely.

For unlike the days of Escobar, where all paths led to him, the cocaine industry is now built on thousands of micro cartels who handle a single stage in the production without being able to implicate one another.

Father Peter Walters, whose charity Let The Children Live! runs Casa Walsingham, which has 350 street children enrolled in educational programmes, says bloody gang warfare in Medellin's barrios is putting children's lives in danger.

"These gangs are able to control activities such as extortion, prostitution and the distribution and sale of drugs," he says. "The drivers of buses and taxis who do not pay up are likely to be killed or have their vehicles burned and the consequences for shopkeepers who refuse to pay are equally severe."

With the shanty towns under the control of drug gangs, children are often recruited to work for them.

"There is a huge amount of violence and deaths connected with the drug trade and children are often the victims."

Many are roped into the trade by becoming hooked on drugs first, something that becomes apparent when I go on a night patrol with Martin Rosendo, the charity's chief coordinator.

"They start adapting to street life and design a life based on their earnings, which is difficult to break away from," he says.

"The first thing that happens is they start using drugs to become integrated with a group. A child who refuses will be rejected."

Bazuco is the drug of choice among Colombia's street dwellers. Costing just Dh1 a hit, it is a toxic and addictive combination of cocaine and solvents mixed with brick dust.

It is rife among the children dwelling under the arches of Prado metro station, who repeatedly suck air out of plastic bags containing a blob of the sickly yellow gunk.

They start to congregate at dusk under the railway line, their baby faces caked in glittery make-up and dressed in skimpy outfits.

Boys and girls cluster around the roadside bars, whose owners stare out blank-faced, oblivious to the innocence lost on their doorsteps.

The children greet Martin and his accompanying helper Claudia like old friends, but with half an eye on potential customers in this busy hub, a few streets from the tourist centre. Each transaction earns them Dh100.

One 14-year-old girl is pregnant and HIV positive. Another claiming to be 16, but clearly much younger, skips up with a tray of Chiclets yet is far too provocatively dressed to be selling chewing gum.

Most of the girls are nursing pregnant bellies and most - thanks to the bazuco - have glazed eyes.

Troubled by the lack of protection for its young, the Colombian government introduced the Infancy and Adolescence Law in 2006.

It banned children from sleeping on the streets, the sewers were closed off and, ostensibly, children's rights were enshrined in law. However, charity workers say children are still sleeping rough.

But there are moves to overhaul the situation. Two years ago, Medellin's then-mayor Alonso Salazar launched a scheme in a former psychiatric hospital to pluck children off the streets and give them the impetus to improve their health, give up drugs and learn new skills.

Last year, Dh4.3 million of funding from Bienestar Familiar went towards five non-government organisations in the city and helped get 1,245 children off the street. But this is a drop in the ocean of the 100,000 children in Medellin deemed vulnerable, according to the government's own figures, and who "lack the basic conditions to fully develop all the skills and potential as human beings".

Indeed, the national statistics office (Dane) estimates of the 207,610 children under the age of six in Medellin in 2007, more than 70 per cent were in a position of vulnerability.

Elena Luz Calle, of Bienestar Familiar in Medellin, says it sometimes feels like a losing battle: "Every day there are more people on the streets. It is very difficult to know what the future holds. The problem is not just economic. If these children have care throughout their lives, they could be better citizens."

She adds the national government has a policy in place called Mas Familias En Accion to identify poorer families and target help where it is needed most.

Under the scheme, work began in 2006 on building dozens of nurseries and schools in some of the most deprived areas.

Martha Cano, a coordinator of the Montecarlo nursery catering for 300, says: "These children would never have gone to nursery before and 30 per cent of the mothers are teenagers, so we are working with people who have not been in an education system."

Indeed, under Alvaro Uribe - a former mayor of Medellin and former president of Colombia - there has been huge investment in the city under the slogan "from fear to hope".

A cable car completed in 2010 that connects the poorest barrios in the mountains to the city centre has meant an increasing number of people have flocked to the heart of Medellin to explore job opportunities. Former no-go areas such as Santo Domingo Savio in the north, where one of the city's five architecturally impressive library parks was built on a mountaintop, are now fully integrated. Library parks are buildings that serve as both community centres and public space.

And the 140,000 residents of Comuna 13, one of Medellin's most violent neighbourhoods, now have a giant outdoor escalator to travel into the heart of the city instead of clambering up and down hundreds of precarious steps. The Dh26m escalator climbs 1,260 feet up a mountainside. But symbolically, it has been one step forward and three steps back.

While the murder rate has plummeted by 37 per cent in a year, it has been followed by 11,000 forced displacements and more than 750 unexplained disappearances attributed to gang wars.

In June this year, Medellin put armed soldiers in place in Comunas 8 and 13 because of the increasingly violent turf clashes.

"You cannot solve these things in one day," says government advisor Federico Restrepo. "Of course we still have problems, but now you can find the best architectural buildings and the best transport systems in the poorest places."

Father Walters worries children are being enticed into criminality with the promise of a roof over their heads and easy money: "It is very complicated working in these cities. You cannot go and ask questions because you might be perceived as a spy."

Meanwhile, he is starting his fourth decade of helping children off the street with educational and vocational schemes from carpentry workshops to mothers' groups - although sometimes all he is asked for is a hot meal.

"The children here have a hunger for affection and if they find adults who listen, they open up."

And there are success stories, such as two of his graduates, aged 17 and 19. Homeless from the ages of nine and 12, the two young women have given up prostitution and now aspire to be a policewoman and a maths teacher.

One says: "There are many girls out here who do not think of anything except work and drugs, but it is no life at all. I could not see a future."

Then there is Yeison Henao, 28, who grew up on top of a rubbish dump in Moravia - the city's landfill site - but is now back at his birthplace working at a government-built arts and culture centre created on the same spot.

"We have never had anything like this before," he says. "It is a dream come true for me to finally get what I have always wanted for my country."

The cable car seems an apt metaphor for the entire nation: as sparkling and new as the swanky high-rises in wealthy El Poblado, it glides over the mass sprawl of shantytowns built precariously on the mountainside.

Their residents might be able to ride the cars to more salubrious neighbourhoods, but those riches are out of reach.

As the cable car passes over Santo Domingo Savio, there is an enormous poster plastered to a corrugated tin roof of an open mouth, hands cupped around it.

It could be a scream, a cry for help or a shout of protest. There is no caption. Only an open mouth.

* Tahira Yaqoob is a former features writer for The National