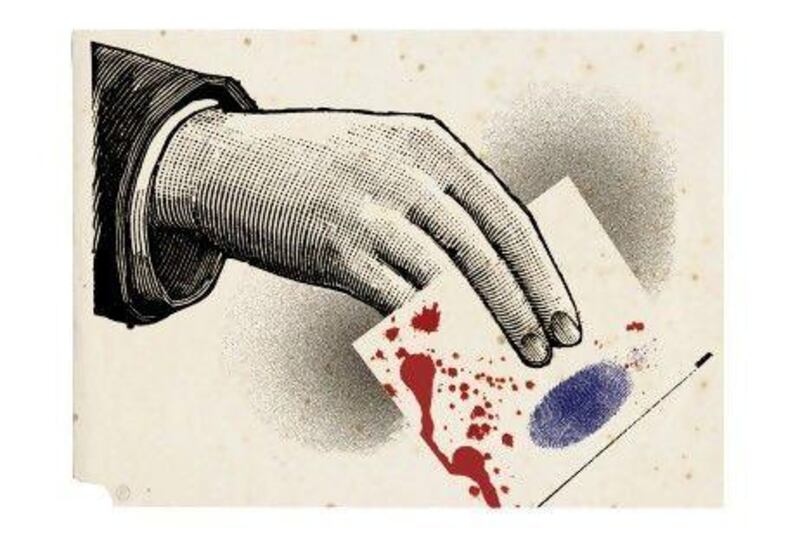

The electoral ink in which nearly two million Libyan voters dipped their fingers a week ago has momentarily replaced the stain of blood in a country still riven by chaos and violence.

Just a few months ago, Nato jets bombed the killing machine of Muammar Qaddafi. Now the first elections in the country for five decades represent not only a milestone on the path of democratic transition, but also what appears to be the bucking of a regional trend.

With final results yet to be declared, it is a bloc of centrist-nationalist parties and politicians (dubbed "liberal" by outside observers) that leads the polls - and not, as was expected by most political pundits, the Islamists.

If confirmed, it will be the first victory for centrist-nationalist forces in post-Arab spring elections - a distinctive democratic signature for similar groups in neighbouring Egypt and Tunisia to study.

Yet while the outcome of the elections for the National Congress matter, Libya's future unity and political composition will be decided much more by two factors that are related to these elections: the weak performance of the Islamists, and a last-minute political deal between Tripoli and Benghazi.

Voters went to the polls on July 7 not knowing what to expect in Libya's first free national election in the aftermath of Qaddafi's downfall. The context was challenging: Libyans had no prior voting experience, and most nursed scars from Qaddafi's long rule, as well as having sustained trauma from the violence that followed his removal. The month of June alone was marred by tribal infighting that left more than 100 dead and 500 injured.

One day there were no political parties; the next more than 140 crowded the political scene. The country's first democratic test was akin to a political stampede: 2,600 candidates (including more than 600 women) competed for just 120 seats set aside for individuals. A further 80 seats were reserved for political parties.

For the Islamists, long hunted by Qaddafi's regime, this seemed a sure recipe for success. It would have been a repeat of the scenarios, in Egypt more than in Tunisia, that catapulted their counterparts into power in other countries.

In particular, the Justice and Construction Party (JCP), the political arm of Libya's Muslim Brotherhood, must be wondering what happened and how its leaders failed to appeal to voters. The JCP's unlikely rival was the National Forces Alliance (NFA), which stands for business, strong ties with the West and "moderate" Islam.

The same self-evaluation applies to Hizb Al Watan, an Islamist party formed just months ago. One of the party's key leaders, Abdel Hakim Belhaj, the former chief of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, will be at loss to explain how he and fellow Islamists failed to rise to the occasion in Libya's first democratic elections.

The situation of both Islamist parties is a powerful indication of how the "Islamist Arab Spring" momentum is being slowed, if not reversed.

It will be some time before proper stock can be taken of the situation. However, what is certain is that Islamists seem to be paying the price for two components of their public image: their orchestrated character assassinations of their political rivals during the campaign and, more importantly, a reputation for toting guns that brings back memories of the brutal regime's hated revolutionary committees. Libyans will not soon forget the killings that went on all over the country long after Qaddafi was killed.

In addition, the Islamists might have suffered because of their pre-emptive declaration of their intention to impose Sharia law, even before the constitution has been framed. Even if other Libyans view this preference for an Islamic political system as legitimate, the parties appear to have jumped the gun by advertising their commitment to a Sharia-based system.

The Islamist parties took advantage of a constitutional amendment that allowed for the formation of political parties on the basis of religion. Yet sustaining their militias and their quasi-military status is clearly a difficult proposition in a post-conflict society such as Libya. The country is undergoing a civilian project of democratic reconstruction, and legitimacy now can derive only from transparent, legal and non-military activity - the barrel of the gun should have nothing to do with political power.

The effect of the elections, which apparently served to unify the country, almost had the opposite effect. Were it not for a last-minute political deal, the elections might not have gone ahead. That one policy decision could have long-term consequences for Libya and keep it from breaking apart.

In the run-up to the election, the eastern province of Libya, centred around Benghazi, demanded a greater share of seats in the parliament. The region, known as Cyrenaica or locally as Barqa, was the heart of the uprising against Qaddafi. The demand for greater political representation carried a threat of further violence.

Mustafa Abdul Jalil, the head of Libya's caretaker government, under the auspices of the National Transitional Council (NTC), should be noted for a stroke of genius in resolving the crisis. Mr Abdul Jalil stripped the newly elected parliament of its constitution-framing function and gave those powers to a new 60-member body, which will be directly elected by Libyans. According to this arrangement, each of the three regions of the country, Tripolitania in the north-west, Fezzan in the south-west and Cyrenaica in the east, is allocated 20 seats in the constitutional-framing committee.

To this effect, Constitutional Amendment Number 3, which was passed on the eve of the polls, averted electoral chaos and mutiny in oil-rich Cyrenaica.

Mr Abdul Jalil, who will resign from office once the NTC is disbanded and a new government is formed, may finally have proved his worth in defusing a potentially calamitous situation.

This innovative solution may emerge as a point of distinction for Libya's democratic transition. It is certainly a page worth borrowing from the Libyan book of "democracy", most notably for Egypt, whose Constituent Assembly's future remains uncertain.

It remains to be seen which will be more indelible: the electoral stain of the ink that, for once, united "new Libya" at the polls, or the bloodshed that followed its revolution.

For now, however, Libya has passed a historic test with flying colours. A new beginning, and other tests, await this new Libya.

Dr Larbi Sadiki is a senior lecturer in Middle East Politics at the University of Exeter in the UK, and author of Arab Democratization: Elections without Democracy