The narrative of sport is often constructed around heroic victories and soul-destroying defeats. But there are also entire chapters devoted to controversy, to what-might-have-been moments, that left one set of supporters exultant and the other scarred for life.

How many Englishmen will ever forget Tofik Bahramov, the linesman from Azerbaijan, who insisted that Geoff Hurst's ferocious strike had crossed the line in extra-time during football's 1966 World Cup final? The West German defenders, including Franz Beckenbauer, claim to this day that it never did.

When Frank Lampard's shot from long range was wrongly disallowed in a second-round match at the World Cup in South Africa last year, an older generation of German fans would have felt a sense of justice, however delayed.

English fans, left red-faced after their team had been played off the park by a vibrant German side, had a cartoon villain to hide behind in Mauricio Espinosa, the Uruguayan assistant referee.

A couple of years ago, Invictus, a cinematic reconstruction of South Africa's 1995 rugby union World Cup triumph, was released. While it narrated the rainbow nation story/myth to a wider audience otherwise likely to be unaware of it, the film glossed over one of the key moments of the campaign.

In the Durban semi-final played in pouring rain, South Africa prevailed only after a late French drive was ruled out. The giant figure of Abdelatif Benazzi stretched every sinew to plant the ball over the line, but Derek Bevan, the Welsh referee, ruled in the Springboks' favour.

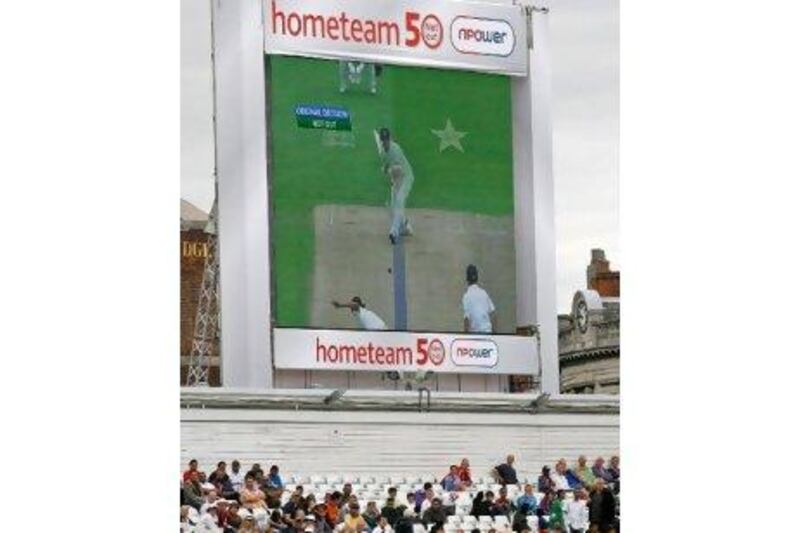

In the age of the slow-motion television replay, even the venerable sport of cricket has not escaped its share of debate. Many now remember the 2005 Ashes as the greatest series ever played. England came back into it with a thrilling two-run victory over Australia at Edgbaston in Birmingham.

Only, Michael Kasprowicz was not out according to the rules of the game, his hand having come off the bat handle before the ball took the edge through to Geraint Jones. Billy Bowden, the umpire, did not spot it, and even though subsequent replays revealed what had happened, there was no Decision Review System (DRS) at Australia's disposal.

The system itself can confound, as was evident during the World Cup semi-final between Pakistan and India at Mohali.

Initial replays appeared to suggest that Sachin Tendulkar was out lbw to Saeed Ajmal. Yet, when Hawk-Eye traced the ball's trajectory, it was just missing leg stump. Tendulkar scored another 64 runs, India won and enough conspiracy theories were spawned to keep 10 Warren Commissions busy.

India had expressed their displeasure with the system earlier in the tournament, after a tie with England in Bangalore. Though replays using Hawk-Eye showed that Ian Bell was leg before, he was reprieved because the technology became less reliable when the point of impact was more than 2.5 metres from the stumps.

When first exposed to the review system in Sri Lanka in 2008, India used it pitifully. Sri Lanka were far more adept and it unquestionably helped them win the series 2-1. Since then, the Indian board's refusal to accept the DRS and certain players' reluctance to embrace it has led to widespread accusations of churlishness.

"The Hawk-Eye is yet to convince us," said N Srinivasan, the Indian board's president-elect, recently. "This is a technology that deals with the projection, trajectory and angle of the ball. And from where the cameras are placed, it cannot give a fool-proof solution."

Some would argue that a near-perfect solution is better than none at all. But the DRS debate has far too many shades of grey.

As of now, there is no standardisation. Some bilateral series employ it, others do not. The International Cricket Council (ICC) leaves it to the discretion of the two boards involved in each series.

There is also no uniform technology. Some use Hawk-Eye, others use Virtual Eye, which has more than twice as many frames per second, but a different methodology. Hotspot, which uses military technology and infrared cameras, is another tool, but one seldom employed because of prohibitive costs.

One workable solution would be for the ICC to finance the needed technology so every series is played under the same conditions. Most boards do not have the money. And to expect television companies, who have already staked a fortune in buying rights, to do so is to expect endless milk and honey.

There is also a good case for increasing the number of unsuccessful appeals that a team can have from two to three. Having a limit in place forces teams to be both honest and judicious.

An even better solution would be to grant more powers to the third umpire. Allow him to step in via a walkie-talkie and correct the obvious howler. Also use sensors to detect no-balls so that umpires do not have to look down and then up before making a game-changing decision. You do not need military hardware for that.