Almost 300 minutes of live debate have now passed between the two candidates for the presidency of the United States, and dozens have been spent debating foreign policy.

The usual subjects have been touched upon - China, Russia, Iran and Israel, Egypt and Libya: the strategic concerns of a superpower in an uncertain age.

But there were questions that were not asked, indeed cannot be asked.

Look at the discussion about Iran in the final debate on Monday night and it is clear there are limits to the potential range of questions.

Questions about a military strike on Iran - whether by Israel or the United States - are limited to strategic and logistical questions. Who would be tougher on Iran? Who would threaten Iran more? Is Iran sufficiently frightened of America? These are the arguments of playground bullies, not serious diplomats.

What is never asked is a more fundamental question: what moral or legal right does America have to launch a pre-emptive strike on Iran?

Listen to President Barack Obama talk about how US-led sanctions on Iran are "crippling" that economy: "Their oil production has plunged to the lowest level since they were fighting a war with Iraq."

Nowhere is it asked what right the US has to inflict such catastrophic damage on ordinary people.

In 1996, the then US secretary of state, Madeleine Albright, was asked by a journalist whether she felt the death of half a million children in Iraq as a result of the US-led sanctions was worthwhile. The journalist pointed out that was greater than the number of children who died in Hiroshima. "We think the price is worth it," said Ms Albright.

Such a question is impossible to imagine in a presidential debate. No moderator would dare ask it - indeed, it would probably never occur to them to do so.

The acceptability of the pain of sanctions, and whether the US has the right to inflict such pain, is never questioned. It is an unexamined assumption that the ability to project force and cause economic pain confers the moral authority to do so.

That is not new. It was how the British and French empires justified their theft of land and resources around the world.

Indeed, the European nations offered a range of moral justifications for their increasingly aggressive involvement in Asia and Africa. It was right and proper to do so, they argued: they were "saving" the locals, or expanding civilisation, or protecting free trade.

Such self-serving justifications covered a range of morally reprehensible acts, such as political murder, expropriation of land, imposition of foreign settlers and forcible change of laws and governments.

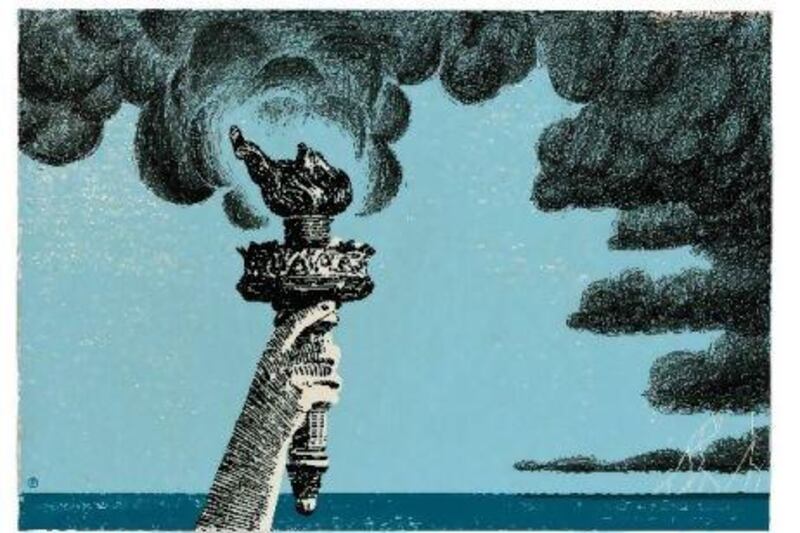

That couching of the straightforward exercise of power in moral language continues today. Such language has been used to justify locking people up without trial, kidnapping, unlawful imprisonment, the indiscriminate slaughter of people from the sky, the systematic destruction of cultures and nations.

Just because the words are different - rendition, targeted killing, regime change, drone strikes - does not make the underlying acts less horrendous.

What is astonishing is how easily even well-educated politicians and journalists believe it. As long as the language used is moral and the purpose apparently high-minded, all sorts of immoral acts and low skulduggery are possible.

Those who defend these actions do so in a narrow matrix of ideas that glorifies the primacy of western power. It is fuelled by a comforting self-righteousness that suggests the might of western weapons used against others is also - how coincidental - right and proper.

They cannot step outside this matrix to ask whether any state has the right to inflict harm on another, and by what right.

Nor is it enough to say that this is the way of the world, that this is realpolitik and how politics is done.

Those who argue this way wish to imply a touching naivete on the part of those who question the exercise of American power, or who suggest the possibility of a different world.

That line of argument speaks to an excessively cynical worldview - and is, in any case, insufficient as a justification.

First, it is undemocratic - Americans are not uneducated people who need to be lied to and fooled to allow the proper exercise of power to continue.

But also, the idea that this veneer of moral language is known to be false - that this is just how the game is played and everyone knows it - ignores the very large number of politicians, journalists and diplomats who genuinely believe they are exercising power for moral ends. They - and perhaps the two presidential contenders are in this category - would be horrified to recognise the brutal realpolitik ends to which their apparently moral policies have been used.

It is precisely for this reason that these unexamined questions are so dangerous. And precisely for this reason that they need to be asked.

If this appearance of morality is unexamined by journalists and analysts, so is the appearance of impartiality.

Both candidates carefully couch their policies in universal values. When Mitt Romney spoke of promoting the principles of "human rights, human dignity, elections", he spoke as if the United States were loftily seeking to bring these values to whichever benighted regions lacked them.

Yet the inconsistencies are obvious. Where is the dignity of those on whom bombs rain down in Yemen, Pakistan and Afghanistan? How are human rights in the Palestinian Territories supported by America funnelling money and weapons to Israel? If Mr Romney likes elections so much, why did he suggest he would have stood more strongly by Hosni Mubarak, or suggested people should "look closely" at the Islamists in power?

This appearance of impartiality also governs the relationship of the US to the most intractable regional conflict, in Israel and Palestine. The US political class veers between seeing itself as an independent arbiter - highhandedly taking an overview of these two bickering parties - and seeing itself as the staunch defender and prime weapons supplier to one side. As Mr Romney said, his administration would "have Israel's back". That is not the language of the referee.

Yet perhaps the most insidious aspect of the debates is the way they are about America alone. What would a strike on Iran mean for America's reputation? What would not attacking mean for American deterrence?

Never asked are questions of how this would affect those struck by the bombs and those left behind.

If Iran is subject to a military strike by the United States, the ripples of repercussions will spread across the region. Aside from possible military strikes against Iran's neighbours, there will an economic hit from the disruption to shipping.

A strike would entrench a fading conservative regime in Iran, creating policies that would adversely affect young people and liberal Iranians. Iran would seek a greater role in Syria and Lebanon, and perhaps elsewhere, dragging more weapons and instability into those countries.

These questions are not mere questions of political theory: there are real people who live in these countries, whose lives - from commuting to work, to buying a house, to finding jobs - will be affected by American bombs and their aftermath. Much of what comes after is unknowable - but a great deal is predictable.

But such questions are never asked, never even considered in the tight matrix of beliefs that sees might as right and morality as the prerogative of the powerful.

The foreign policy debates have often displayed a callous lack of emotion, as if there were no human bodies at the ends of those policies. It is the callousness of power, the entitlement to rule that recognises that those who make the bombs fall will not be the ones picking up pieces from the rubble.

[ falyafai@thenational.ae ]

On Twitter: @FaisalAlYafai