When public figures are buried, it is on social media that they are first praised and first condemned. So it was that when the news was announced, late on Sunday in the United States, that Fouad Ajami, one of the greatest Arab-American scholars, had died of cancer, it was on Twitter that tributes to his life and criticisms of his work were first made.

Few, it appears, have forgiven Ajami for cruelly dismissing the death of Edward Said. In that way of alleged remarks, it mattered little whether it was true or not, but whether it sounded true. And Ajami was a public critic of the Columbia professor, calling his Orientalism theory a “cult”. Said, in turn, accused him of having “unmistakably racist prescriptions”. It was Ajami’s perfidious criticism of Arab and Muslim figures, often utilising the language of the conservative right but insulated by virtue of his ethnicity, that brought him such contempt from liberals and such praise and recognition from conservatives.

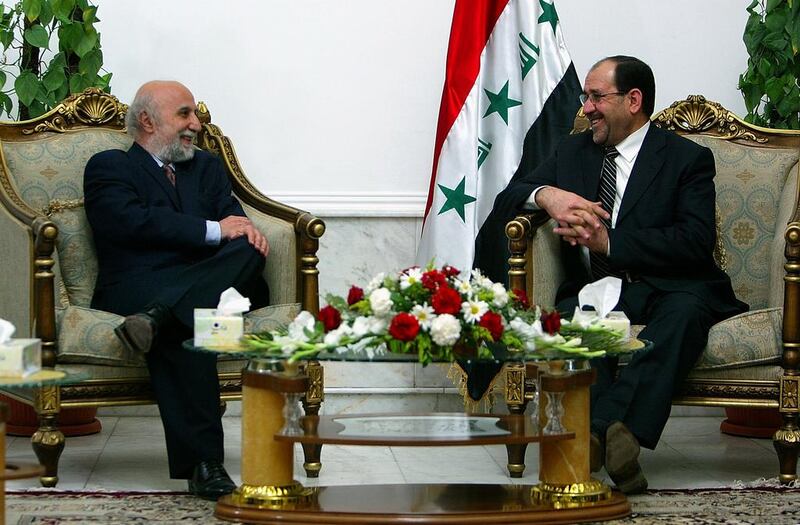

Fouad Ajami was an extraordinarily talented scholar, the first Arab-American to win the MacArthur Fellowship, and, as director of Middle East studies at Johns Hopkins University, a leading figure in US policy for two decades.

For most outside of political and academic circles, however, Ajami came to prominence in the run-up to the 2003 Iraq war, when he emerged as a committed cheerleader for the US invasion. It was Ajami who was the source of Dick Cheney’s now infamous remark that the Iraqis would greet US troops as liberators, a false prospectus that led to the deaths of thousands of Americans and tens of thousands of Iraqis.

The chief criticism of Ajami was not that he was a bad scholar, but that he too often used that scholarship in the service of power, echoing back to the powerful their own views. When the American journalist Adam Shatz, in a 2003 profile, called him “a native informer”, he was identifying Ajami in a tradition of writers who use the orthodoxies of others to condemn their own people. That label, echoed by others before and since, proved hard to shake off.

Ajami was a genuinely brilliant thinker, a man who understood the subtle relationship between politics, economics and culture. He was able to see beyond the rhetoric of a generation of Arab leaders, understanding how the dispossession of an old economic elite by military leaders like Gamal Abdel Nasser – of whom he was once an admirer – had led to political upheaval that required authoritarianism to dampen. His two best books, The Dream Palace of the Arabs and The Arab Predicament contain both insight and empathy for the region in which he was born and lived for nearly two decades.

Over the years, however, that fraternal feeling towards the Middle East dissipated, dissolved by his proximity to the conservative fringes of American power.

Seeking to explain the Arab world to a conservative audience, he was unable to identify US power or the actions of US allies like Israel as agents for any of the troubles of the region. Seeking to avoid blaming his friends, he blamed the Arabs, utilising essentialist ideas about culture and history, unable to view the Middle East except through an Orientalist lens.

His frequent appearances on television and in print were characterised by a profound lack of intellectual generosity towards an entire people and a lack of intellectual curiosity towards an entire region. His view of the Arab world was narrow, lacking an understanding of its societies and myriad cultures; the flourishing of arts and culture, science and literature in the region had no interest for him.

What interested him purely was how the Arabs might interact with American power. For him, an entire region was passive except when it opposed the exercise of US power.

Like all who sought to use their intellectual gifts in the service of power, he soon found that power is a respecter of no logic but its own. For five decades he was involved in the heavily-politicised nexus of US policy and Middle East scholarship, and, too often, Ajami had to furiously try to keep up with the shifting sands of politics.

He was against Palestinian statehood in the 1980s and for the Iraq war in 2003. Both positions were morally bankrupt at the time he espoused them, yet he continued to defend both long after they had also become politically unfashionable.

His staunch neoconservatism may have been sincere, but his role in the movement was reduced to parroting the prejudices of his supporters and patrons. But there is a cruel irony at the heart of such a relationship: for if the views of his listeners change, his must change too. But the opposite does not occur. For all their lauding of his “expertise”, neoconservatives never had their views on the Middle East changed by his.

In that way, the views in his early work – which are impressive; alongside Sadiq Al Azm’s Self-Criticism After the Defeat, Ajami’s The Arab Predicament remains essential to understanding intellectual trends in the post-1967 Middle East – were contorted by proximity to power. His carefully expressed arguments were sometimes indistinguishable from anti-Arabism, his generalisations about the Middle East and its many peoples sounded like Islamophobia.

With a whole region of politics to parse and a whole history to explain, Fouad Ajami frequently shone his scholarly light narrowly: when he wrote about the Arabs, he too often came to bury them, too rarely to praise.

falyafai@thenational.ae

On Twitter: @FaisalAlYafai