How bizarre is it that football can seem so blase about corruption and match fixing. You come to expect that from administrators, sure, guided to varying degrees by inertia and wilful blindness. But why has there not been, I do not know, greater concern, fear or even outrage from fans, followers, players and former players?

The easy and obvious comparison to make is with cricket and its own corruption, which seems to have cut so much deeper into the skin. There are fans who stopped watching the game altogether. Others watch every game with a cynical, jaundiced eye, unable to believe that a run-out, a dropped catch, a loose shot, a no-ball could be anything other than a fix.

There are former players and journalists who are much the same, unable to get beyond the anger and betrayal they felt.

Football? The greatest game in the world regularly pulls off one of the greatest tricks by repeatedly sidestepping deeper questions about its integrity and moving on.

It is not as if the revelations of Europol on Monday, that nearly 400 games across various countries and tiers of European domestic and international football (and 680 across the world) are under suspicion of having been fixed, are the first of their kind.

In fact, football pretty much guarantees a corruption scandal every few years. Even the most cursory glance would take you from England in the 1960s (involving Sheffield Wednesday players) to allegations against the Leeds United sides of Don Revie, to incidents in the 1980s in Belgian football, to the infamous Bernard Tapie and Marseille case of 1993, to the pretty serious charges against Bruce Grobbelaar, to the truly strange case of the floodlights at Charlton Athletic's stadium and an Asian betting syndicate.

Is that enough? No?

There are long-standing concerns about football in parts of east Asia as well any number of leagues in eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Yet as inevitably as each new scandal emerges, so it slips off in the self-aggrandising world of football, like some Teflon politician.

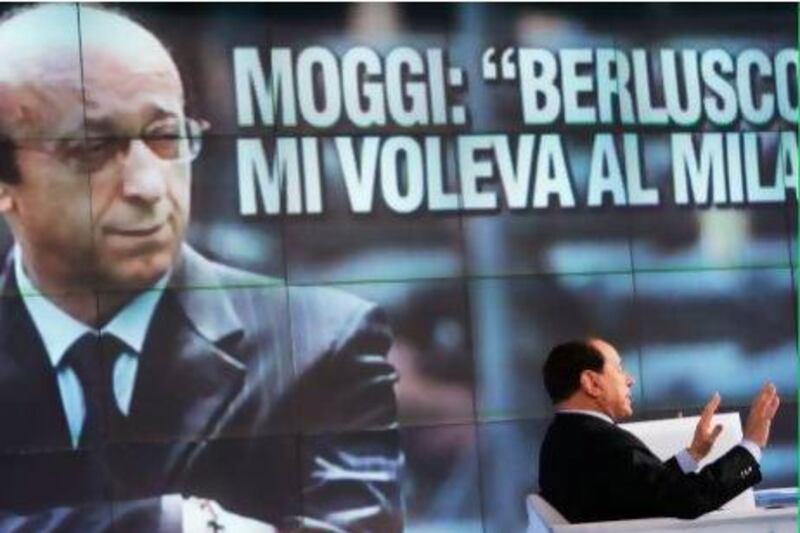

Italy is an instructive example, particularly when compared with, say, Pakistan in cricket. Like Pakistan, Italy has gone through multiple fixing controversies.

But compare how they - the Italian national team, Italian clubs, Italian players - are perceived around football to how the Pakistan cricket team and its players are in their world. The moral outrage directed towards Pakistan and the stigma and suspicion has stuck resolutely to them since 2000. To Italian football it has come and then pretty much gone.

There have been some mildly disapproving murmurs from outside occasionally and introspection within but, generally, if Italy lose an international, or an Italian club loses a game they should not, it does not really raise any eyebrows. That is not to do with race or even whether the approach to one country in one sport is right and the other wrong.

It is just strange that football deals with essentially the same problem so differently, not just in terms of how it fights it (or not), but how it reacts to it.

There are two parts to this. It says a little about the bubble of hyper-morality cricket continues to exist within, in which cricket is not just a sport, but a higher, virtuous pursuit of some kind. When the bubble is pricked, results are ugly and amplified.

But it also has much to do with the way the two sports work. Cricket is small in serious membership. Every scandal and controversy becomes further concentrated within this world and so more intensely felt; because it is so small, it becomes everyone's problem.

Football's global nature works against this. There is not one central administrative point (Fifa is, of course, but it does not have the control that the ICC has) and the international and domestic equation is completely reversed, which has its own impact. The first thing football does is to diffuse reaction.

Why should a football fan in England care at all about a third-division game in Germany that might be fixed, or an international between Honduras and Ecuador that was? It is not their problem, or even the problem of their football association, or even their continental association.

But the problem with that is obvious. It will continue to not matter until the scandal involves a big enough name or unless it happens to your club, your league or your country. And then it will be too late, anyway.

Follow us

[ @SprtNationalUAE ]