When India detonated its first nuclear bomb in 1974, only five states in the world had declared nuclear weapons – and all five of them sat together as permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. As symbols of power go, the ability to incinerate cities is a potent one, yet India has long craved a further one, a permanent seat on the Security Council. This week, it received a nod from the US president: an endorsement that Indians should sit permanently on the council, not that the US would lobby to help get them there.

Will it happen? Unsurprisingly, Indian press and politicians are excited at the prospect of their country acquiring a permanent seat. It would seal a remarkable transformation for the world's largest democracy.

Yet that day is far, far off, if it comes at all. Security Council reform has been talked about for decades and is likely to be discussed for years to come. It is a contentious issue. The council comprises five permanent members, all of whom were chosen as the victors of the Second World War, with a further 10 members elected for two-year terms. It is a structure rooted very clearly in the power dynamics of the past and one that rising powers have lobbied hard to change.

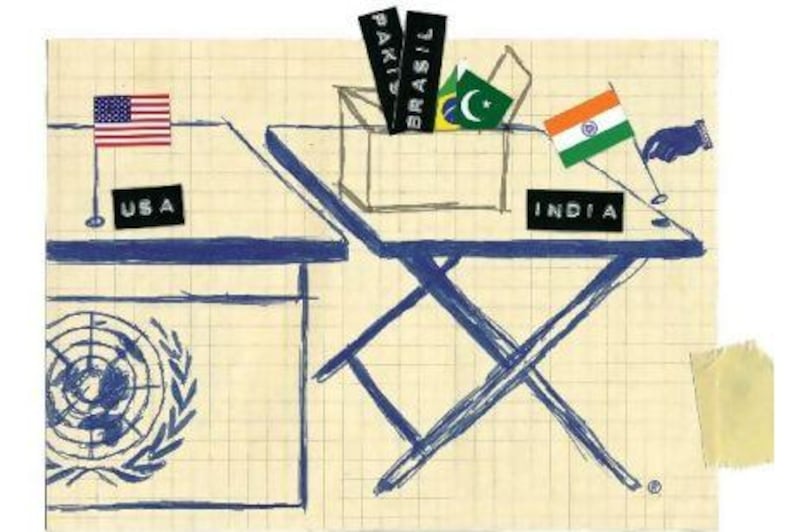

Under proposals discussed in 2005, the five permanent seats would be expanded to include a further five or six members, with the most often quoted being Japan, Germany, Brazil, India, Egypt and perhaps an African country. Japan and Germany have particularly good claims to membership. They are consistently among the top three largest funders of the United Nations. The African Union is clear that it expects a seat for one of its members – but which one? The Arab League would also like one, but no one candidate obviously suggests itself. Then there is Indonesia, from where I write this, the world's fourth-largest country and a democracy. f the Muslim world is to have a seat, surely Jakarta should be in the running.

That gives a glimpse of the complexity of choosing candidates. But consider their enemies, too. Four countries - Japan, Germany, India and Brazil, have formed the G4 group to support each other's candidacies, yet each faces stiff opposition from its neighbours. China opposes Japan and, more tacitly, India, seeing them as regional rivals. Pakistan opposes India's bid, while South Korea opposes Japan's. Argentina and Mexico argue that a South American seat should go to a Spanish-speaking country (Brazil's national language is Portuguese), while Italy wonders why Germany should be chosen ahead of itself. Many others ask why Europe needs a third permanent seat when the world's biggest region, Asia, has only one.

The chief difficulty is that a new Security Council would "lock in" any changes to the world order for decades to come, just as the original council did in 1946. But the world is in constant political flux and countries that are weak may quickly become strong and the strong weaken. Countries that are developing rapidly, such as Indonesia and Turkey, may want reform to be delayed until they are in a better position to negotiate entry for themselves. Other countries – European nations, for instance – may feel their bargaining position gets weaker the longer discussions take. Absent a defining event like the Second World War, the talkers will just keep talking.

But put all of that aside and ask for a moment what would happen in a world where India was a permanent member of the UN Security Council. In this hypothetical world, much would have changed: there will have been political and military conflicts, economic ups and downs and unexpected events with unforeseeable consequences. But ask the question simply and it is clear that India's role on the council, and its new role in the world, would depend more than anything else on its relationships with two of the current permanent members, the United States and China.

China and India's relationship matters because, with India as a permanent member, they will be the two countries on the council who have most recently fought a war. (Even if the other members of the G4, Germany, Japan and Brazil were also admitted, that would still hold true.) A brief battle in 1962 over the Himalayan border ended with a Chinese victory, a humiliation India has not forgotten.

Worse, the reasons for that conflict remain live. The 4,000km-long border between the two countries has never been demarcated and much time, treasure and troops have gone into bolstering the border without any resolution.

India's other main conflict with a neighbour, the dispute with Pakistan over Kashmir, might by then still remain live, and China is a player in that conflict, too. Pakistan has ceded an area of Kashmiri territory it holds to China, but India maintains a claim over it.

All of this, despite the volume of trade between the countries, suggests serious friction that might yet escalate. In recent years China has shown itself willing to wage diplomatic battle over its territorial claims. That it might do so with another permanent member of the world's highest security body, potentially pitting 40 per cent of the world's population into a war, would severely undermine the stability the council is meant to ensure.

India's problems as a permanent member could stem not only from its distance from China; they might also occur because it is too close to the United States.

India's foreign policy in recent years has remained defiantly pro-US; indeed it is hard to think of many recent political issues on which the Indian government has disagreed with the US stance. Unlike other emerging countries such as Turkey and Brazil, India has been reluctant to throw its weight around, preferring to toe a US line. It is difficult to imagine a political situation arising in the next few years that would change this strategic choice.

Having spent decades in this mode, it is unlikely a permanent Indian presence on the Security Council would suddenly change its direction. The European powers there, plus the United States, would find themselves with another ally to support their views. What might that mean for present-day conflicts, such as North Korea, where China finds itself on the opposite side of New Delhi and Washington? What might it mean for Pakistan, where the intractable conflict in Kashmir has brought India and Pakistan to war: would an emboldened India seek punitive measures against its neighbour, or seek to impose a settlement Pakistan might view as unfair? And what retaliation might that bring from Pakistan, given its role in Afghanistan? These are predictable questions today, with unpredictable answers, but the questions that arise tomorrow may be harder.

A glimpse of what might happen if India becomes a permanent member will come over the next two years. India was last month elected to one of the 10 non-permanent seats. Its term begins in January. What happens then will focus minds on what role India might take in a restructured Security Council. If it continues to follow the West's line, even on issues such as sanctions on Iran, over which it has previously expressed scepticism, that would please the US but concern its (and the West's) rivals.

If on the other hand it takes the path of Brazil and Turkey, both currently non-permanent members, and tries to strike out on its own diplomatically, it might well bolster its position for the future, at the risk of alienating a United States that so recently endorsed it.

Yet there is a warning for India in all this, for so long aspiring to be a member of the top table: when you get there, you may not like it. To see why, consider the trajectory of world power. A declining West may find it better to use international institutions set up at the height of its power than to deal individually with states from a position of weakness. China already finds itself chafing under new international obligations, preferring to strike better deals with its neighbours one to one. By the time India is admitted to the club, it may find international rules constrain it rather than allow it to exercise its by then considerable power.

Think back to India's nuclear test in the 1970s. It was only because India had not signed up to the global Non-Proliferation Treaty that it was not punished harshly for violating its terms. Had India agreed to that particular international rule, it is highly likely that today it would not have nuclear weapons – and the clout that goes with them,.

Faisal al Yafai is a journalist and currently a Churchill fellow. You can follow him at twitter.com/faisalalyafai