Professor Soumitra Dutta, the dean in charge of the Abu Dhabi branch of the international business school INSEAD, has a message for Facebook-banning bosses: get your heads out of the sand. Rather than worrying about how to resist the growing importance of social networking sites, leaders of organisations would be wiser to spend their time looking at how to use them, Dr Dutta argues in his book Throwing Sheep in the Boardroom: How Online Social Networking Will Change Your Life, Work and World. Co-written with Matthew Fraser, a senior research fellow at INSEAD, the book was published by John Wiley and Sons and is due for release this week.

"If you look at the top 10 websites around the world, seven or eight of them are social networking sites," he said. "People are spending an enormous amount of time on that, and it's a phenomenon that's only increasing. It's not going away, and the challenge is how do you leverage it and become part of this phenomenon? You cannot hide from it. Hiding is not an option." He attributed the widespread banning of social networking sites at workplaces, including top-tier institutions such as Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, to anxiety among chief executives about the technology's importance and potential.

"Most companies around the world today ban these sort of social networks," he said. "There's an excuse that says, 'this is a waste of time, people chat with their friends, this is not productive time'. But the reality is that people are confused." Although Dr Dutta might find himself briefly aligned with the cause of the workplace slacker, he is far from one himself. He has written nine books, and co-authors a widely quoted annual World Economic Forum Global Information Technology Report that ranks countries according to their IT readiness. He advises the government of Qatar on IT policy and chairs a committee on innovation for the European Commission. As a professor in business and technology at INSEAD, he oversees the business school's centre for teaching and research on the digital economy, organised in partnership with companies such as Morgan Stanley, Cisco and Intel. Much of his time is spent flying between INSEAD's campuses in Abu Dhabi, Singapore, France and New York. In his latest work - the title is a reference to the Facebook action of "throwing a sheep" at someone in order to get their attention - he and Mr Fraser argue that Web 2.0 is fundamentally changing the way that identity, status and power are constructed and allocated in society.

"Organisations are not very good at tolerating different identities," he said. "If you are part of a certain religious group, or a certain organisation, you often hide the parts of your identity that the organisation doesn't want to see. And what you are seeing through the social networking space is more and more opportunities for people to project themselves differently. So what we are seeing is identities are getting disaggregated."

But this disaggregation can be fraught with problems. One case study in the book tells the story of a British police officer who was selected for an important promotion that was then retracted when his bosses discovered his comments on a gay networking site. Other problems can await young people who post their collegiate partying exploits on their Facebook profile only to regret that decision once graduation rolls around and the job hunt begins.

"Today, when you apply for a job, what is important is not necessarily what you give as a CV," Dr Dutta said. "It's often the top 10 things that appear in Google when they Google you. And it's almost guaranteed that almost every HR executive today Googles for the key applicants to the position, and what might come up in these online searches may be stuff linked to these other identities that may not be what you want to project."

Nonetheless, the sum total of these clashing forces was towards greater freedom of expression and diversity of identity, he said. "The pressure to conform is a little bit less in this emerging world." Similarly, status is given in a more democratic fashion. Where once it came with a dignified job title or, for example, the favour of a record company, today it increasingly comes from the public. "Classically, the way the music industry works is you have a few large companies who act as gatekeepers," he said. However, with the rise of sites such as MySpace, musicians are able to post their work online directly and "you are able to become a star without having this industry gatekeeper".

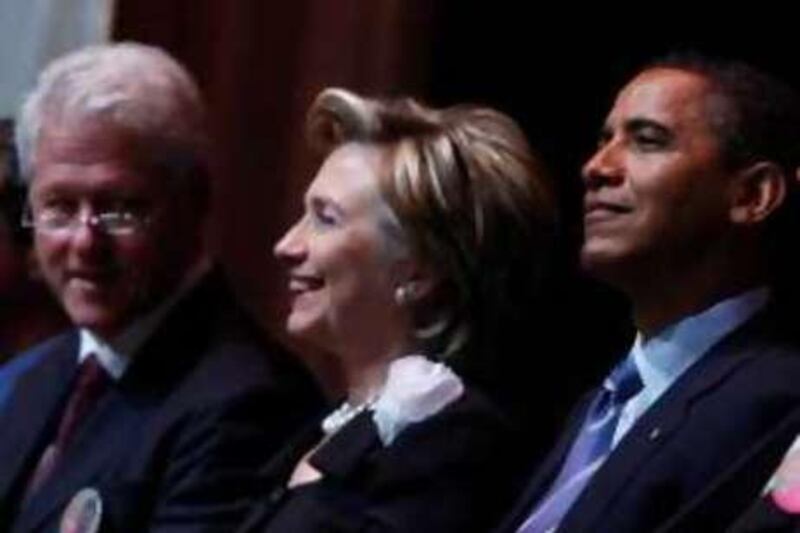

Power was becoming similarly decentralised, he said, particularly in the political arena, where the process of fundraising and organising has been revolutionised by the internet. "Obama is a wonderful example," he said. "I think he is probably one of the most astute politicians at using the bottom-up power, the diffuse power of the younger Democratic base to confront and, in fact, defeat the established hierarchy that the Clintons had control over. The Clintons had control of the Democratic machinery for several years, and he was able to change that and leave power to a much more diverse group which was outside the traditional Democratic power structure."

The book likens Web 2.0 technology's potential for creating social change to the power provided by the invention of the printing press to create the social conditions for the Reformation. "If you suddenly give voice to millions of people around the world, you will find more and more cases of greater citizen participation in society, be it in civil governance or in social movements," Dr Dutta said.

But because the technology is so new, there are still many questions that need to be answered. One of the most provocative in the book deals with who owns the profile users create on Facebook. "You might create some things when you are 18, and then when you're 25 you want to delete it, but you can't delete it. Who owns it? As technology improves, in 10 or 20 years, you might have virtual avatars who could take your place. If these virtual avatars could take your profiles, that creates interesting questions."

The global technology also raises regional questions. The book describes the story of a Moroccan man who was jailed for creating an online profile of a member of the country's royal family, and eventually freed following pressure from the international community. Dr Dutta said such situations showed how governments and new technologies needed to come to terms with each other. "It will force people to eventually rethink some aspects of social norms because there will be people pushing the boundaries, one way or the other," he said. "But the way I look at it, it need not be a threat. It can be a positive input. If societies and governments actually thought through constructively how to engage this power, to get more engagement from their citizens, it can actually lead to tremendously powerful results." khagey@thenational.ae