With the euro crisis nipping at Italy's finances, local budgets have been severely squeezed. To try to ease the pain, the jewel in the country's tourist crown is targeting ticketless public-transport users who do not play fair, Colin Randall, Foreign Correspondent, writes from Venice

Think Venice and, automatically, you think water.

The heart of this stunningly beautiful city, built on more than 100 islands in a lagoon at the northern summit of the Adriatic Sea, can be explored only by negotiating its canals and crossing its bridges.

For many, the emblem of Venice remains the gondola, the long rowing boat that served for centuries as the main method of getting around.

But these days the gondoliers navigate their craft mainly for short tourist excursions - typically €80 (Dh380) for 40 minutes - or private ceremonies.

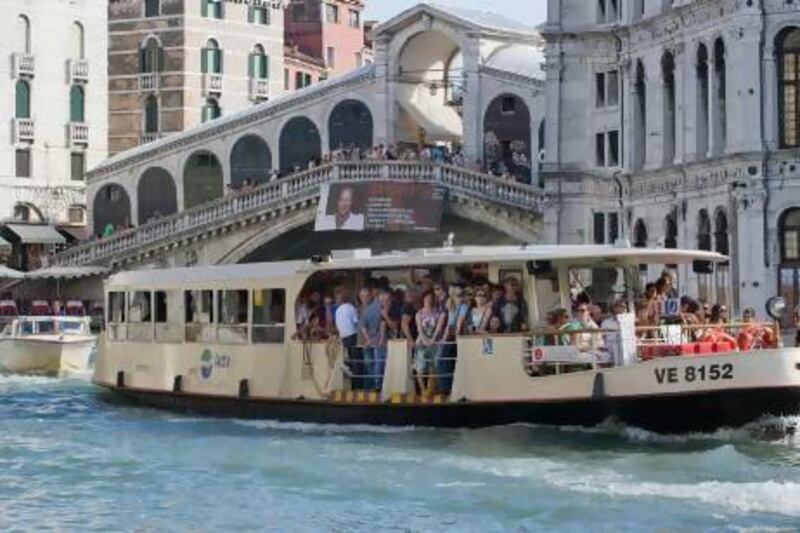

In their place as the principal public transport system has developed a bustling network of canal buses, or vaporetti, that carries millions of passengers as effectively as the underground railways of, say, London, Paris and New York.

In harsh economic times, with Italy feeling a particularly chilly financial drought, the service has to contend with dwindling regional funding and rising costs, especially for fuel. And as part of the struggle to balance the books, the public company that runs the canal buses, Azienda del Consorzio Trasporti Veneziano (ACTV), is waging war on fare-dodgers.

The impression gained by many users of the vaporetto service between hotels, bus and railway stations and such tourist magnets as St Mark's Square, the Lido and the islands of Murano and Burano, is of a service that is easy to avoid paying for.

Passengers wander on and off untroubled, for the most part, by ticket control barriers. Boats serving key destinations are often so crowded that even if an inspector appears, only a few travellers will be asked to produce valid tickets before the next stop is reached and observant offenders can smartly disembark.

Failure to produce a ticket carries a fine of €52 plus the cost of a single journey €7 unless the passenger makes the first move, approaching an employee on boarding the boat to offer payment if, for example, ticket machines were out or order. On a busy weekend in May, one ticketless American woman could not claim when challenged to have made any such approach, yet seemed to have little difficulty in convincing an inspector to take no further action than selling her one.

But appearances may be deceptive. ACTV is adamant that it has the problem under control and that with 140 inspectors covering the network, the American was rather fortunate not to have been fined. But officials acknowledge that further action is needed to stop revenue draining away unnecessarily.

"I could talk about this for three days," says Marcello Panettoni, president of the AVM Group, which owns ACTV. "You may be lucky in a short visit and encounter few controls and it is possible to use the service on a single day and not be checked. But you should certainly expect to be asked to produce your ticket if you used the service on, say, three days in a week."

He points out that in a country where fare evasion is a serious issue - the national rate on public transport is around 20 per cent - the vaporetto service's record is comparatively good. Fare-dodging in April, for example, was estimated at just 2.5 per cent, with a total of 612 vaporetto passengers found without tickets and fined, mostly paying on the spot or within days. Last year, inspectors imposed about 50,000 fines, although this figure includes penalties for people using the company's buses on roads away from the canals without paying. Fare-dodging on those buses was estimated at 5.6 per cent last month.

But even if ACTV sees reason to believe it has had some success against cheats, the evasion that does occur costs the company about €1.5 million a year on its own calculations, which may be conservative.

The loss of revenue is especially disturbing at a time of need for financial rigour in the way the service operates. The Veneto regional government reduced its subsidies by €13m in 2012/13 and €8.5m the year before; the figure currently stand at €76m. Meanwhile, annual fuel costs have risen by €4m. There are some 3,000 employees but ACTV insists it wants to make the economies necessary without laying off staff.

"We are trying to reorganise services and find economies without sacrificing the service to the public or having to lose employees," Mr Panettoni says.

"We are going to eliminate some journeys rarely used and re-organise the whole company starting from a strong spending review. We are cutting and reducing all company costs, re-organising all services in order to be more competitive and efficient."

This suggests greater savings are needed than the €6.7m economies found in 2012.

The reduction if not eradication of cheating has a small but important part to play. Ticket control barriers have been introduced at a few key stops, including Tronchetto, Accademia and others on the tourist trail, and more are planned.

They would not be practical for safety reasons at all the network's 80 stops but Mr Panettoni, who is also president of Italy's public transport operators' association, insists that controls are already energetically enforced. Inspectors target each of the 23 lines every other day in rotation.

He does promise further measures, however. "We want to improve it further by a combination of technology and staff, with control barriers at more stations and more people to carry out controls on board," he says.

The aim is to make the system as cheat-proof as, for example, the London Underground or Paris Metro where those seeking to avoid paying have to vault barriers or "double up" with paying customers as they pass through.

Checks are being stepped up at some of the busiest stops such as Rialto, Piazzale Roma and the railway station, and more staff will be used to verify tickets before passengers board the boats if installing new barriers is not an option. "I can assure you that only a few people could escape our controls," the president says.

Venice attracts 26 million visitors a year and the vast majority rely for part of their transport needs on the vaporetto routes.

"The importance of public transport is becoming nowadays fundamental," Mr Panettoni adds. "European cities and especially Italian ones are not suitable for private transport because of their structure and the presence of numerous historical monuments.

"In Venice, we must make a bigger effort compared with other cities because we are managing public transport on water, with all the problems and costs that means.

"But we have to connect places and people and have to be 'green', investing money to be more and more environmental respectful. This is the aim for the future: let our city be more liveable."

[ buisness@thenational.ae ]