Last month I wrote how Turkey needed to rebuild constructive relations with its energy-rich neighbours. Two dramatic announcements later, and it seems to have done just that.

But big obstacles still lie in the way of improving Turkish energy security: Baghdad, a Mediterranean island, and the Kremlin.

On Thursday, Abdullah Öcalan, the leader of the PKK Kurdish separatist organisation, called a ceasefire. This capped years of cautious negotiations between Mr Öcalan, in jail since 1999, and the Turkish government.

On Friday, the Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu apologised on the phone to his Turkish counterpart, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, for the death of nine Turks in the 2010 storming of a ship that was taking aid to Gaza.

And a week ago, dramatic happenings on the island of Cyprus: the terms of the European Union-led bank bailout required depositors to pay a 10 per cent levy, triggering anger and frantic last-minute negotiations.

What is the energy significance of these events? They may open routes for two of the most exciting current oil and gas discoveries to reach markets, enhancing Turkey's economy and energy security on the way. The Turks need gas in particular to fuel their growing economy, that has become too dependent on Russia and on supplies from Iran threatened by sanctions and winter disruptions.

The 29-year insurgency waged by the PKK in south-east Turkey may be nearing its end. The Kurds of Syria have largely thrown off central government control. The Syrian Kurds have balanced ambiguously between the president Bashar Al Assad's government and the Syrian opposition, and gaining leverage over them has become urgent for Ankara.

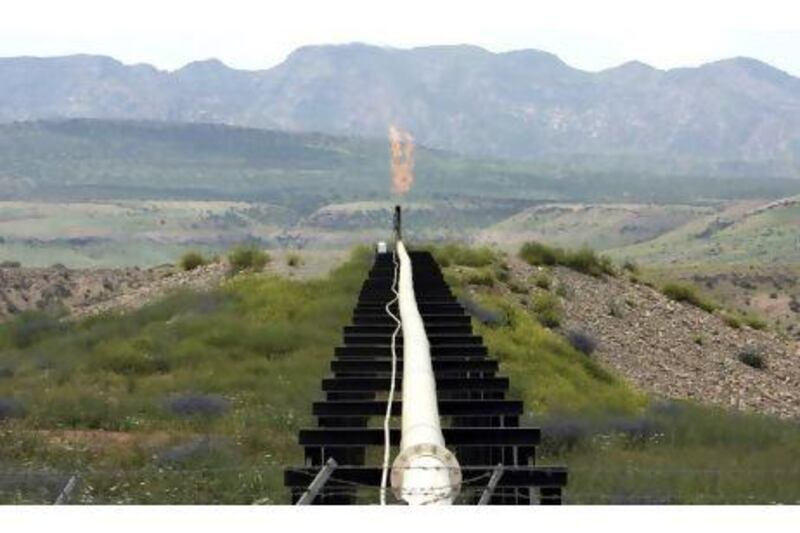

Under Mr Erdogan, Turkey has developed increasingly close economic links with the autonomous Kurdish region of Iraq, where international companies have found major oil and gasfields.

But independent Kurdish oil and gas sales are blocked by Iraqi government policy, and relations between Baghdad and the Kurdish regional authorities in Erbil have deteriorated sharply.

Permitting direct large-scale exports would require the Turks to take the dramatic step of breaking with the Iraq central government. For now, this is a pipeline too far - but a solution to the Kurdish dispute surely brings an Ankara-Baghdad showdown closer.

Meanwhile, in the eastern Mediterranean, Israel has found some 30 trillion cubic feet of gas, enough to supply it for the next 80 years. Cyprus has also discovered a major field, and Lebanon is launching exploration this year.

Mr Netanyahu's apology to Mr Erdogan adds to recent rumours of discussions over a pipeline. This is probably the cheapest way for Israeli gas to get to Turkey and Europe - and would help to rebuild a key regional alliance for Tel Aviv.

But Israel's route to Turkey is blocked by Lebanon - with whom it is technically at war - and Cyprus, divided between Greek and Turkish Cypriots.

Turkey disputes the right of the internationally recognised Republic of Cyprus to explore for gas, in the absence of a political settlement.

When the deposit haircut was announced, the Cypriot government offered to compensate savers with "gas bonds" backed by future revenue from its hoped-for offshore gas fields.

The idea then emerged for Russia's Gazprombank, loosely linked to its state gas giant Gazprom, to offer its own bailout, in return for stakes in those fields. This would allow the Kremlin to defeat, divert or delay a threat to its market dominance.

Turkey has opposed the use of Cypriot gas to pay such compensation. But to make use of the thaw with Israel, and access Mediterranean gas, Mr Erdogan will have to replicate his Kurdish rapprochement with Cyprus. Foreign governments may be lesser obstacles to Turkish energy security than domestic nationalists.

Robin Mills is the head of consulting at Manaar Energy, and the author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis and Capturing Carbon