The country hosts the World Economic Forum starting today, having won praise for its economic strategy and political deftness. But its current-account deficit worries the IMF, and the nation does not warrant 'Bric' status, says the man who coined the term. Frank Kane reports.

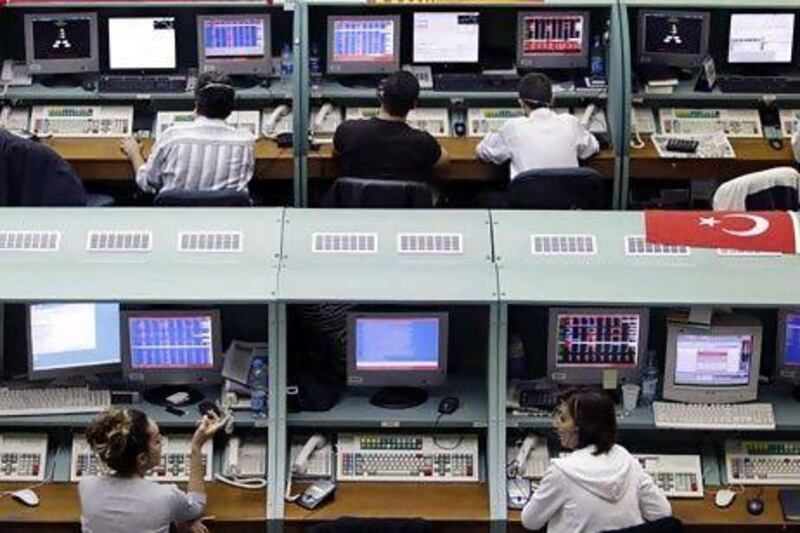

The sheer scope of the World Economic Forum (WEF) sessions that begin in Istanbul today demonstrates Turkey's growing ambition to be not just a regional but a world player.

Billed as the forum for Europe, the Middle East, North Africa and Eurasia, the three-day event underlines Turkey's increasing influence in its neighbouring regions. There is even some muttering that the Turks are seeking to recreate the sphere of influence of the Ottoman Empire, which broke up some 90 years ago.

That is an exaggeration, no doubt, but the gathering of 1,000 leaders, politicians, economists and business people in Istanbul is second only to the annual Davos meeting of the WEF in scale and importance.

It comes as Turkey has drawn gasps of admiration from Central Asia to the shores of the Atlantic for its handling of the fallout from the global financial crisis, its economic strategy, and for the policy course it has adopted during the Arab Spring.

Although the country suffered along with the rest of the world at the height of the financial crisis in 2008 and 2009, with negligible GDP growth followed by a 5 per cent decline, its recovery has been perhaps the most impressive. In 2010, it reported 9 per cent growth and last year 8.5 per cent.

Other measures also show Turkey's economic and financial performance has been outstanding. Public-sector debt is low, banks are well capitalised, and the nation has cut inflation dramatically from the 70 per cent annual rate a decade ago to about 10 per cent today.

All the other yardsticks are moving in the right direction, too - per-capita GDP and productivity are improving faster than in most other countries. Turkey's potential seems unlimited, with a growing, young population feeding a domestic consumer market that will keep the nation's industry busy for years.

So, should Turkey not have been the first country to break into the Bric league - the original club of the dynamic economies of Brazil, Russia, India and China - before South Africa joined to make it the Brics?

This is where the doubts about Turkey first creep in.

"Turkey is not currently, nor is it likely to be, big enough to warrant Bric status," says Jim O'Neill, the Goldman Sachs economist who coined the phrase Bric in 2002. "I've defined a true Bric as anyone with 5 per cent or more of world GDP today, or a realistic chance of getting there by 2050. Turkey is exciting, has bags of potential, but is not a true Bric."

He rates Turkey as one of the eight growth markets in the world, along with the Bric originals plus South Korea, Indonesia and Mexico.

That may be only a mild disappointment for the Turkish leaders, headed by the prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who will address the WEF in Istanbul.

After all, Turkey may find compensations in not being a "true Bric" if it means doing without the problems of corruption in Russia, or stifling bureaucracy in India.

But it is not just Mr O'Neill who is having doubts about the Turkish economic miracle. A number of economists and analysts are also critical of the country's economic and financial fundamentals, and of its recent policy moves to ensure growth.

Christine Lagarde, the managing director of the IMF, has paid tribute to the country's economic performance of the past decade but has also warned of "vulnerabilities" that she says are arising in the economy.

The IMF expects the GDP growth rate to fall sharply this year, to 2.3 per cent.

Ms Lagarde said that the country's large current-account deficit, where the value of a country's exports fall short of its imports, left Turkey at the mercy of the international capital markets, and that it needed to "implement a sound combination of macroeconomic, fiscal and structural reforms to sustain stability and growth in the future". Coming from the IMF, this was only a little short of a vote of "no confidence" in Turkey's policymakers.

Other economists have warned of the "hot money" flowing into the country's economy, to the detriment of genuine foreign direct investment in its industrial, manufacturing and services sectors.

"Turkey's current-account deficit leaves it dependent on foreign inflows, which have become more volatile, with higher portfolio investment and short-term - non-trade - external financing," says Philippe Dauba-Pantanacce, an economist at Standard Chartered bank in Dubai.

"As long as [the current-account deficit] is so large, Turkey will be vulnerable to a sudden halt in foreign inflows. The deficit is Turkey's sword of Damocles."

William Jackson, a European emerging-markets economist with the London-based consultancy Capital Economics, echoes that view. "Turkey remains one of the most vulnerable economies to a fresh external shock."

The most likely avenue from which an "external shock" might appear is the European Union. With more than 40 per cent of Turkey's exports going to the EU, any deepening of the euro-zone debt crisis could provide just the jolt some economists fear, and cut GDP growth prospects for this year to within margin-of-error range.

The more pessimistic are already forecasting a contraction of the Turkish economy this year.

But it is not just from the West that problems could present themselves for Turkey.

To the East, the repercussions of the Arab Spring, and particularly the conflict in Syria, presents the serious potential for long-term disruption to the economy.

While Mr Erdogan has won plaudits in the Middle East for his stance during the upheavals in North Africa, and on the Palestinian Territories, a deterioration of the security situation on Turkey's south-eastern border will present him with a much more immediate threat, and potentially a big destabiliser to the economy as a whole.

The Turkish politicians and officials hosting the WEF in Istanbul will be characteristically sensitive about what they regard as unjustified attacks on their economic record.

When Standard & Poor's, the American credit-rating agency, suggested a rather gentle downgrading in its forecasts for the economy, Mr Erdogan threatened sanctions against the agency.

In 2009, he made a name for himself, and many admirers in the Arab world, by storming offstage during a heated debate with Israel's president, Shimon Peres.

The global opinion leaders in Istanbul, however, would probably prefer a more measured response to his country's economic challenges.

twitter: Follow and share our breaking business news. Follow us

iPad users can follow our twitterfeed via Flipboard - just search for Ind_Insights on the app.