On the final steps leading up to the third level of gloomy rust-brown stairs, the light suddenly bursts free, like dark clouds splitting after a summer storm.

A narrow stairwell opens to a wide platform, dappled with sunbeams piercing thousands on thousands of metal stars.

Here are the first drops of what's known as the Rain of Light, falling through the nearly completed canopy that will cover the Louvre Abu Dhabi.

It's a colossal engineering and design challenge that, after two years, is now all but complete.

Here on a platform of scaffolding is the first glimpse of what will draw visitors in their hundreds of thousands from around the world.

Like a jungle canopy, the museum's dome stretches in every direction. It encloses a space larger than two football pitches and the height of an 11-storey building, but the impression it creates in real life seems even bigger.

The few workers still remaining on this level are busy wiping and polishing the last grains of sand still clinging to the dome's aluminium-and-steel cladding. Their tools are feather dusters and cans of a citrus-scented cleaning spray. A faint scent of lemons hangs, incongruously, in the air.

The biggest task now is to take down, rather than put up. From the day in December 2013 when the first 41-tonne piece was lowered into place, the pace of construction has rested – literally – on 119 temporary towers.

¦ Watch: Louvre Abu Dhabi's temporary towers come down

As the 7,000-tonne dome was assembled, the towers held up all through the winter and the summer of 2014. By December 2014 – almost exactly a year later – the now-complete structure was lifted off the towers using 32 powerful hydraulic jacks and gently lowered onto four concrete permanent support towers.

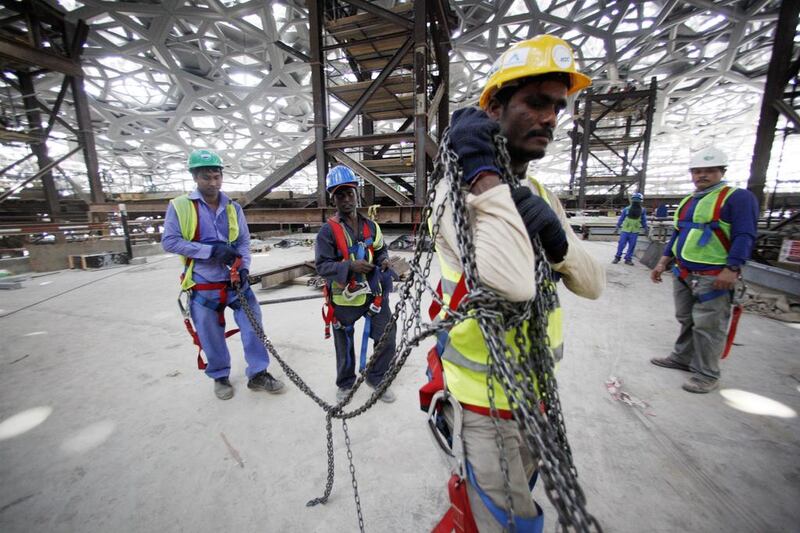

For the past six months, the temporary towers have had a different function, providing a platform for up to 700 workers attaching the layers of star-shaped cladding below the dome, while above them, others perform the same task for the outer layers.

Now that lengthy task is finished, and as the hundreds of tonnes of steel are dismantled, so the vision of the museum's French architect, Jean Nouvel, is revealed.

Many of the towers were originally lowered into place in one piece, using a giant 1,600-tonne crawler crane. But taking them away is tedious, labour intensive work. There's no space for cranes, so each piece must be dismantled, lowered and removed by hand.

Teams of workers heave the beams across what are the roofs of the museum's galleries, while a shower of sparks and brilliant glow reveal a welder breaking the large sections into smaller pieces.

Until it's done, the next stages cannot begin. They include mundane tasks such as waterproofing, but also the installation of the glass skylights that will illuminate the main galleries. At present, several of the towers rise through the empty rectangles where the skylights will be fitted, blocking their installation.

In total, there are 500 trusses, 30,000 metres of beams and 17,000 square metres of platforms and scaffolding to be hauled away.

"We have a lot of galleries below that can only be completed once these towers are removed," explains Austin Mascarenhas, a construction manager for Turner Construction International.

High above his head, a group of workers begin to dismantle a bridge that connects two towers and is part of the ever-shrinking level-three platform, the highest, which gives access to the underside of the dome.

More than 4,600 pieces, nearly all of them unique in size and shape, are being fixed into place – the work here is nearly complete.

The temporary towers that first held up the dome were once the most visible signs of the museum's existence. Several of the galleries have risen up around them, while piece by piece, the structure of the dome has hidden them from the outside world.

Until December, they were the physical supports for the dome, some capable of bearing loads of up to 280 tonnes at a single point. Piece by piece, the 85 preformed steel elements that would form the dome were rested on the towers, four for each one.

Like a giant jigsaw, it was only when all the pieces were in place and bolted together that the weight could be shifted from the towers to the permanent nine-metre concrete piers that now support the structure.

Under the dome, the remaining temporary towers still retain an enormous presence, even in the vast space that has been created for temporary exhibitions once the Louvre Abu Dhabi is ready to open. Dark and heavy, they rise up towards the rays of sun now penetrating the dome.

On the third and highest level, the platform supported by the towers is already retreating to the edges of the dome, allowing a bird's-eye view of its sweeping curves. There are two more levels to be cleared until the ground floor is reached.

Much remains to be done before the museum is ready to be handed over for the final stage of assembling its collection of ancient artefacts. But with the towers removed, moving around the site becomes easier.

On the lowest levels, work is so advanced even the bathroom handles are now in place. Once the glass skylights have been fitted, it will become possible to run air-conditioning in the galleries, further improving the work environment.

As encouragement, someone has printed out copies of famous old masters and stuck them to one of the gallery walls. So a Van Gogh self portrait is next to Manet's Young Flautist and The Gypsy, while Leonardo da Vinci's La Belle Ferronière peeks out from behind a scaffolding tower (both these last works will actually hang in the Louvre Abu Dhabi when it opens).

Right now, the real stars of the show are revealing themselves as the temporary towers disappear. "Just see an open sky with all these stars," says Mascarenhas. "It will be very spectacular, no question about it."

jlangton@thenational.ae

Follow us @LifeNationalUAE

Follow us on Facebook for discussions, entertainment, reviews, wellness and news.

The Louvre Abu Dhabi’s first Rain of Light drops shine through

Editor's picks

More from the national