Just as Dubai has had the skyscrapers of Sheikh Zayed Road and Dubai Marina emerge at rapid speed, so the Chinese city of Shanghai has also transformed itself into a space-age cluster of high-rises at a similar pace.

These two cities, arguably the most spectacular of their respective regions, have developed in parallel, so it is perhaps appropriate that Shanghai was one of Dubai’s predecessors as a World Expo host.

The Shanghai Expo, which launched at the end of April 2010, will be a hard act to follow, with the US$58 billion (Dh213bn) extravaganza attracting an expo record of 73 million visitors. It left behind a shiny new airport terminal, an expanded subway and a series of showcase buildings.

Much of the infrastructure would probably have been built anyway in a city developing as fast as Shanghai, but the expo “speeded up” its completion, according to Zhu Tian, professor of economics at Shanghai’s China Europe International Business School.

“When you had a big project like the expo, it was easier for the government to rally the support of the residents to overcome obstacles for some infrastructure projects,” he said.

In late 2009, it was easy to believe Shanghai might miss the April 30 opening date, since the land reserved for the expo was still a vast construction site with shells of buildings that to the untrained eye appeared a long way from being ready.

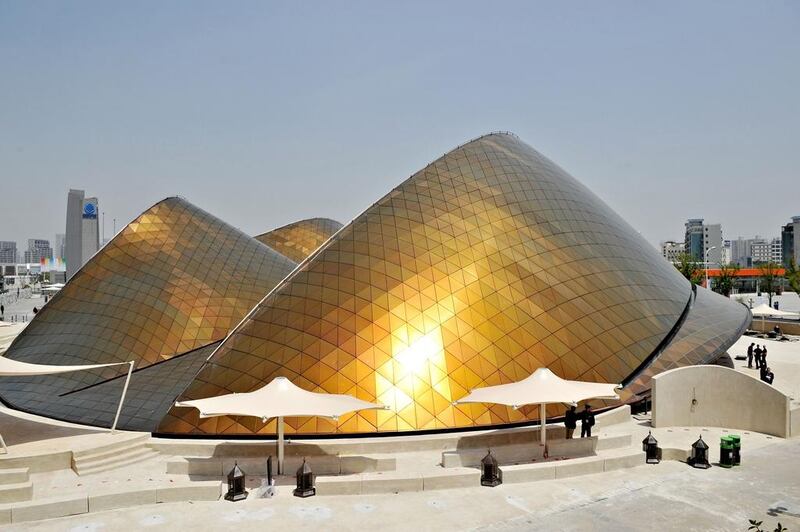

Yet China, like the Arabian Gulf, presses ahead with development projects at a breathtaking pace, so by early April 2010 a seemingly miraculous transformation had taken place: the infrastructure was completed and the national pavilions, among them the UAE’s shimmering golden sand dune, were all set to open. The sense of excitement in the city was palpable.

Even before the opening, hundreds of people were gathering beside the expo site at weekends, providing brisk business for street hawkers selling unofficial souvenirs.

Models of Haibao, the cheery expo mascot, greeted those flying into the city, subway billboards highlighted the work of the thousands of English-speaking volunteers drafted in to help visitors, and there were dedicated expo high street stores selling everything from soft toys to gold models of the China pavilion.

It was no wonder then that when the event itself launched the crowds of visitors were vast.

Queues to enter the most popular pavilions – such as Saudi Arabia’s Imax cinema – lasted for hours, although across the multiple expo sites there was plenty to see.

Under the theme of “Better City, Better Life”, countries used their pavilions to showcase everything from ancient art and traditional crafts to high-tech industry, and put on dance shows, singing performances and spectacular audio-visual films. Such was the scale of the expo that even several days of attendance was only enough to see a fraction of what was on offer.

When the event wrapped up after six months, the total number of visitors, the vast majority of whom were Chinese, exceeded the 70 million target. There were reports, however, suggesting that numbers were inflated by free tickets being handed out and state-run company employees being directed to attend. There were also claims that 18,000 residents had been relocated to make way for the project.

The physical legacy of the event is also ambiguous, since it has proved a challenge afterwards to make proper use of some of the former expo buildings.

That said, the expo can be seen as a coming-of-age for the new China, showcasing of the country’s global clout and staggering organisational capability. It set a high bar for all expos that follow, including Milan in 2015 and then Dubai in 2020.

“It exposed China to the world at a higher level. If people went to Shanghai, it changed their perception. It was a big opportunity for China to tell the world ‘we’ve developed a long way’,” said Stephen Ching, associate professor in the School of Economics and Finance at the University of Hong Kong.

newsdesk@thenational.ae