As workers at Louvre Abu Dhabi remove the towers supporting the museum’s signature roof, the architect’s vision is fast becoming a reality.

On the morning of January 7 this year, Shehab Taha raised his camera and captured something he had never seen before.

The date is clear in his mind – and stamped on the image he took.

Afterwards, as the construction manager for Turner Construction recalls: “It was as if a big load had been lifted from my chest and I could breathe.”

All around him was sunshine. It streamed through the spaces in the complex web of the roof above, but also in a great crescent of light that illuminated a space that was both familiar but utterly changed.

To be strictly accurate, it was what Mr Taha could no longer see that lifted his spirits.

Until a few days earlier, the view from this area of the Louvre Abu Dhabi building site had been a gloomy forest of rusted steel and machinery.

Now the temporary towers that had once been so crucial to the elaborate construction of the new museum’s dome were gone, cut into pieces and dragged away for scrap.

In their place was a glimpse of the future, and the end of the road, when the museum would no longer be a building site but a place of beauty and contemplation.

The vast roof swept down to a curved rim that framed a view west from Saadiyat across the sea channel to Mina Zayed. In one sense, what Mr Taha saw that morning was the light at the end of the tunnel.

“It was a race to build them,” he says of the temporary towers. “Now it is a race to remove them.”

There were about 120 of the towers, put up nearly three years ago on what at the time was the building’s newly completed foundations. At first they supported the jigsaw of the dome as it was joined together.

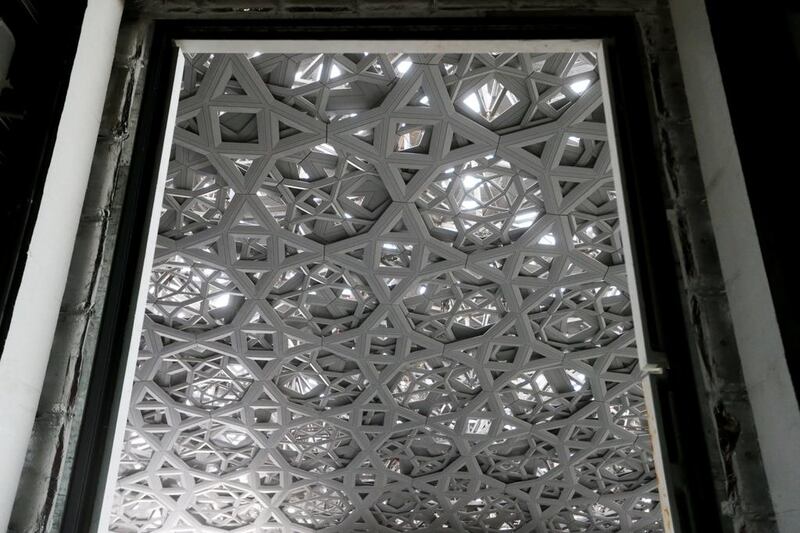

Later they carried a series of platforms that let workers attach a complex network of aluminium stars four layers deep, creating what the museum’s architect, Jean Nouvel, describes as a “rain of light”.

Now most of them have gone. And, to be frank, the ones that remain are nothing more than a nuisance.

Some poke through the roofs of what will become exhibition galleries. Others impede the movement of workers and construction machinery. More block the laying of the stone finish of the exterior plaza.

But the ones in most urgent need of removal are blocking one of the most important stages of the museum’s construction.

Several of them occupied the newly liberated area seen by Mr Taha last month, a series of wide steps leading down to an empty concrete basin flanked by galleries on one side and what will be the museum’s cafeteria on the other.

In the coming months, this area will be flooded. The design of the Louvre Abu Dhabi surrounds it on three sides by seawater that flows to the very edge and, in some areas, even under the dome.

At present this water is held at bay by a combination of earth dams and extremely powerful drainage pumps. Remove these and the sea will slowly but surely reclaim those areas.

The temporary towers still there represent some of the last obstacles before the flooding can begin. Dismantling them is a priority but also a difficult, labour-intensive and potentially dangerous task that involves moving heavy objects in confined spaces.

For Mr Taha, one of the frustrations is that from the outside the Louvre Abu Dhabi gives very little clue of the scale and challenge of the work.

“What nobody really sees driving over the Sheikh Khalifa Bridge and seeing the Louvre from the outside is the temporary towers. The towers weigh as much as the dome, so it is as if you are building two domes, on top of each other.”

It is no secret that the museum’s completion has been delayed. The provisional opening has already been pushed back to the second half of this year, without specifying an exact date (although it is worth pointing out that Barcelona’s Sagrada Familia basilica, begun in 1882, might be completed by 2032).

But if no one involved with the project likes to discuss opening dates, it does not mean there is any lack of urgency among the builders.

Mr Taha, whose company is the project management consultant for the museum, says that Louvre Abu Dhabi is a building of unusual complexity.

It has what he calls “the big five, which are all the complicated disciplines in engineering or construction”.

“In this building you have complicated concrete works, complicated marine works, complicated steel structure, complicated finishes and complicated electromechanical works.”

Most major projects, such as hotels, ports or oil and gas platforms, might incorporate two of these elements.

“But you will never have five complicated disciplines as you have in the Louvre Abu Dhabi,” Mr Taha says.

“Here on the Louvre we have all of them combined and this makes it a very challenging job.”

Challenging, but worthwhile. At last with the removal of the temporary towers, the vision is becoming reality.

“Now you can enjoy this amazing design and this marvellous view of the rain of light and of the dome itself.”

plangton@thenational.ae