The Louvre Abu Dhabi Talking Art Series presents the role of light in the arts and the contribution of Islamic science, in a seminar by Martin Kemp and Sabiha Al Khemir entitled 'Representation and Symbolism of Light'.

During the first reign of the Mamluk Sultan Al Nasir Hasan (1347-1351), Amir Tankizbugha was awarded the illustrious position of shadd al-sharabkhanah, the superintendent of the buttery, or store of the court potables.

The role may have lost something in translation over the centuries, but what is certain is that Tankizbugha was one of the sultan's favourites.

By 1357, during Al Nasir Hasan's second reign, Tankizbugha had risen to become the sultan's amir majlis, responsible for supervising and guarding the ruler's council chamber as well as controlling his various physicians and surgeons. If that was not enough, he was also married to the sultan's sister.

Tankizbugha's name may now merit little more than a footnote in history but it lives on in two glorious objects. Part-tomb, part-monument and part-bastion, the turbah of Tankizbugha was built to commemorate the amir's death in 1362-1363 and is now surrounded by Cairo's Garbage City, or Manshiyat Naser, in the modern suburb of Muqattam.

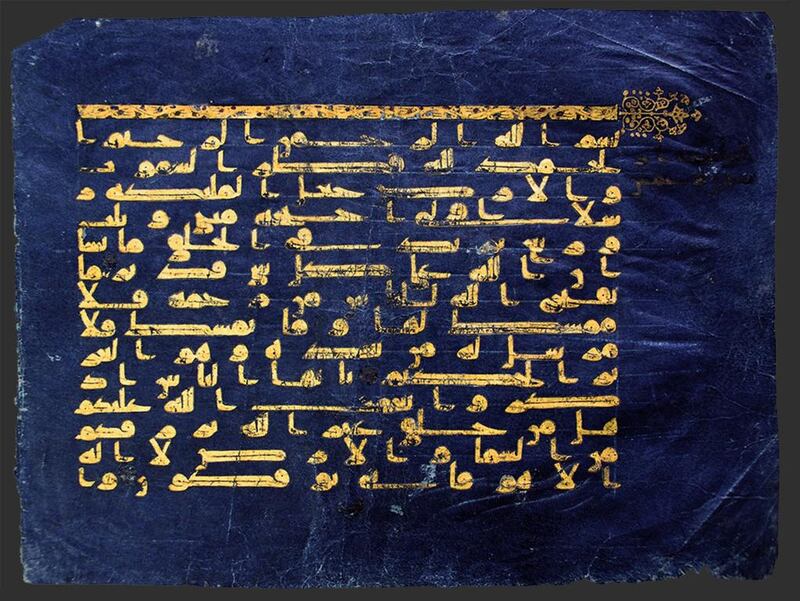

Tankizbugha's other gift to posterity, a 14th-century glass mosque lamp that bears his name, now sits in more salubrious surroundings.

Part of the permanent collection of the Musee du Louvre in Paris, the lamp is one of the loans that will form part of the opening collection of Louvre Abu Dhabi and is the subject of the Louvre Abu Dhabi Talking Art Series event taking place at Manarat Al Saadiyat tonight.

A conversation between the art historian Martin Kemp and Sabiha Al Khemir, senior adviser for Islamic art to the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA), "Representation and Symbolism of Light" will examine the role that light has played in the arts of the Middle East and Europe, and the contribution that Islamic science has made to the development of both.

This evening's panelists know of what they speak. The author of The Science of Art: Optical Themes in Western Art from Brunelleschi to Seurat, Professor Kemp is not only one of the world's most respected experts on Leonardo da Vinci, he is also emeritus professor of the History of Art at the University of Oxford.

Before joining the DMA, Dr Al Khemir was the founding director of the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar, and has curated several international exhibitions including Beauty and Belief: Crossing Bridges with the Arts of Islamic Culture, the largest travelling survey of Islamic art yet assembled in the United States, and Nur: Light in Art and Science from the Islamic World, which opened at the DMA last year.

"The two main words that describe light in Arabic are 'dhaw' and 'nur'," the Tunisian-born Dr Al Khemir explains.

"Dhaw refers to physical light while the word nur refers to light's physical and metaphysical dimensions. It is the same word that occurs in the Quran, in the Surah An-Nur, the chapter on light, where God is described as 'Nurun Ala Nur', light upon light.

"But light is also a shared symbol between all three so-called religions of the book - Christianity, Judaism and Islam - and it also extends beyond these religions. It is in Buddhism, Hinduism and Zoroastrianism," she says.

It was because of these connections that Dr Al Khemir began Nur: Light in Art and Science from the Islamic World, with a display of three exhibits whose provenance is distinctly hybrid: a 19th-century Jewish Hanukkah lamp from Morocco; a 19th-century Persian panel depicting Christ the teacher, with a book inscribed with "I am the light of the world", in Coptic and Arabic; and a mosque lamp, similar to Tankizbugha's, inscribed with part of the 35th verse of the 24th sura of the Quran, the Sura An-Nur, which describes Allah as "the light of heavens and the earth" and "Light upon light".

"I'm not interested in trying to say that these objects or cultures are the same in any way, but what I am saying is that they reflect a dialogue," she says.

"The objects are themselves a mirror of dialogue if only we are prepared to look for it." The fact that Nur: Light in Art and Science from the Islamic World opened at the Focus-Abengoa Foundation in Seville before travelling to the DMA was not entirely a coincidence.

Dr Al Khemir has long identified Islamic Spain - Al Andalus - as both a moment and mirror of dialogue in which the interaction between religions and cultures resulted in enlightenment rather than conflict.

She first explored these themes in the exhibition Al Andalus: Islamic Arts of Spain, which was held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1992, 500 years after Islamic rule came to an end on the Iberian Peninsula, and the curator admits that in some ways her latest exhibition, Nur, represented a continuation of certain underlying themes.

"Spain is the farthest west that Islam went and, especially in the 12th and 13th centuries, places like Toledo played a major role in translating texts from Arabic and Hebrew into European languages. It literally played the role of translating and transferring knowledge, which built the foundations for the Renaissance in many ways," says Dr Al Khemir.

"The history of Spain in relation to Islam is not an easy one and it would be simplistic and inaccurate to say that it was always just a love story, but there are interludes in the history of Al Andalus when Christians, Jews and Muslims lived and worked together and contributed to the knowledge of humanity. That might be worth exploring and that was the key inspiration behind Nur."

For Prof Kemp, Dr Al Khemir's collaborator in tonight's talk, it is in the fields of light, perspective and optics that western art owes some of its greatest debts to Islamic natural science and theories of light.

"One of my interests has been how optics - the science of perspective - reentered the Latin tradition, in Spain initially and then through Europe more widely. It came from Islamic science and was part of a transmission and development of predominantly Greek ideas that were picked up in what used to be Persia and the countries of the Middle East," the art historian explains.

"The great writers on optics, in particular Ibn Al Haytham, had an absolutely key effect on western perspective and views of light."

One of the most profound challenges posed by the works of thinkers such as Ibn Al Haytham, whose seven-volume treatise on optics, the Kitab al-Manazir (Book of Optics), was written between 1011 and 1021, was to force European artists to reconsider how they depicted light.

"There's a general problem which artists began to face. No miracle is complete without a burst of divine light," says Prof Kemp.

"But if you can rationally imitate the appearance of things in nature, if you understand how light is transmitted, how the eye works, and how light is reflected, refracted and so on; if you then establish that naturalistic system, how do you then portray divine light? Why should divine light look any different from very bright natural light?" he asks.

"One of the strategies that you see in Netherlandish and Italian art, is to have demonstrably two light sources in a painting.

"You have light that emanates in a natural way, which moves through the painting, and then you have, very often strongly characterised, a light coming from another direction."

For Prof Kemp, one of the classic examples of this technique can be found in The Flagellation of Christ (1450-1460) by the 15th-century Tuscan painter Piero della Francesca.

Measuring only 2 feet by 2.5 feet and executed on wood in oil and tempera, the painting depicts the scourging of Christ before the crucifixion and is widely regarded as one of the masterpieces of Renaissance art. Given the violence of the scene, the painting is imbued with a sense of harmony, calm and serenity, an effect that is achieved not just by della Francesca's control of geometry and perspective, but also by the curious play of light - a light, Prof Kemp explains, that emanates from the body of Christ.

While Dr Al Khemir is determined not to read too much of the present into the past, she insists that works of art such as Tankizbugha's mosque lamp have the power to not only provide contemporary audiences with a more nuanced understanding of the past, but also to challenge their ideas about the present.

"When we think of the Islamic world, especially in the face of all the events that we know of over the past decade, we are not neutral. But I think these objects have a power that is connected to truth and are, therefore, testimony to a culture and to a way of being that has peace and beauty as its essence.

"I believe they can educate not just people in the West and those who are not directly at home with Islamic culture, but I think that education is also needed for people inside the Islamic world.

"These pieces express something of the essence of Islam and of the way of being, according to Muslim culture, and when we look at them, they are full of peace and beauty. That is what drives me to share what I have learnt about my own culture."

nleech@thenational.ae