Last week, the Financial Times reported that a group of Britain's best-known quantum computing scientists had moved quietly to Silicon Valley to found a start-up called PsiQ.

The lure was the abundance of venture capital that can’t be had in Europe.

The American VC firm Playground, set up by Android’s founder Andy Rubin, has invested in the new company. Judgeing by Playground’s track record – two of its most notable successes were sold to Amazon.com – PsiQ may very well end up becoming part of Big Tech’s trophy collection one day.

It wouldn’t be the first time that Europe’s smartest and most promising tech start-ups have been gobbled up by the behemoths of Silicon Valley and Seattle. Britain’s DeepMind (an artificial intelligence specialist), France’s Moodstocks (a machine learning developer for image recognition) and Germany’s Fayteq (which lets you remove objects from videos) were all bought by Alphabet’s Google.

With every one of these sales, Europe loses ground in the global race for talent. Some 562 European start-ups were bought by US firms between 2012 and 2016, or 44 per cent of the total, according to the advisery firm Mind the Bridge. As the Google economist Hal Varian says, a big reason for buying these companies is being able to poach all of their engineers in one go.

To get a sense of how scarce these resources are, consider that the international talent pool for AI – the “defining technology of our times”, according to Microsoft’s chief executive Satya Narayana Nadella – is alarmingly shallow at about 205,000 people. Germany and Britain are among the top-five hubs for AI talent because of the excellence of their universities. But it’s a bitter struggle to keep such highly prized workers at home.

The primary concern about this brain drain isn’t national pride or flag-waving; it is power. It’s about who controls the huge and politically sensitive data sets on which AI relies.

Google’s takeover of DeepMind is a fascinating example. While the start-up said it would defend its autonomy and stick to its ethical principles after being acquired, the promise didn’t survive its meeting with reality. DeepMind’s reputation took a serious dive when its partnership with Britain’s National Health Service was found to have broken data privacy law in 2017.

Google’s subsequent move to fold DeepMind’s health unit into its own business has troubled privacy campaigners, created internal tensions and led reportedly to staff walkouts.

Europe’s politicians seem complacent in confronting these issues. They see the cash flowing in from Silicon Valley as an unalloyed economic good and talk up investment as a stamp of approval. In France, ministers speak proudly of Google’s and Facebook’s research labs in Paris, which attract everyone from distinguished professors to PhD students. The French minister for digital affairs, Cedric O, said last week that American takeovers of French start-ups were “no problem” as long as the technology wasn’t critical.

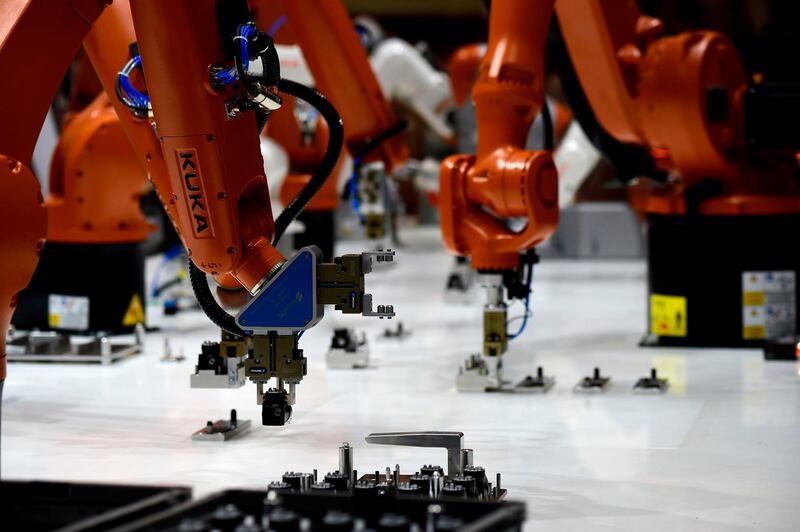

This is shortsighted and shows Europe’s industrial policymakers are still looking at last century’s manufacturers when they’re thinking about sectors they want to protect (no doubt because of the large numbers of jobs involved). Instead of obsessing over mechanical engineering firms such as Alstom and Siemens, France and Germany would be wiser to think more about DeepMind, Moodstocks and Fayteq – or about the German robotics firm Kuka that was sold to China. That also spawned the usual response from European governments regarding the value of what was lost: after greenlighting the sale to Chinese appliance maker Midea, Berlin said the controversial takeover would not hurt Germany's national interests.

Using public money to improve the pay of researchers would also help, as would more hybrid public-private partnerships. Tougher anti-trust scrutiny in technology is also needed – even if it edges toward protecting the national interest. Finally, there’s the dream of a European version of Darpa, the Pentagon agency that fosters emerging technologies for the military.

Europe’s AI and deep tech exodus will continue until its political leaders take the issue as seriously as they do jobs in the metal-bashing industries. Unless they wake up soon, the race is lost.

Bloomberg