Ride-hailing app Careem says it is not afraid of taking on challenges. That’s an admirable quality for a company. Especially when it wants to bring technology-enabled services to a country beset by many challenges, such as security concerns and limitations to digital and physical infrastructure.

In January of last year, Careem launched services in Iraq and now operates in Baghdad, Najaf and Erbil.

While Mohamed Al Hakim, Careem’s general manager for Iraq, says each country has its own particular difficulties, he argues that the challenges may be somewhat unique here.

“All markets at the start they say ‘we are different and there are no challenges like our challenges’. At the same time, in Iraq we run into things like, for example, when there are exams the internet is cut off because the Ministry of Higher Education doesn’t want the [papers] to be circulated ahead of the exams. When there is a religious ceremony, the roads are closed.

"Our business is impacted by both internet and infrastructure,” says the 30 year-old Iraqi executive.

In a country where smartphone penetration levels are amongst the lowest in the world, with 3G services only introduced in 2015, there is a lot of work that needs to be done in regards to IT literacy.

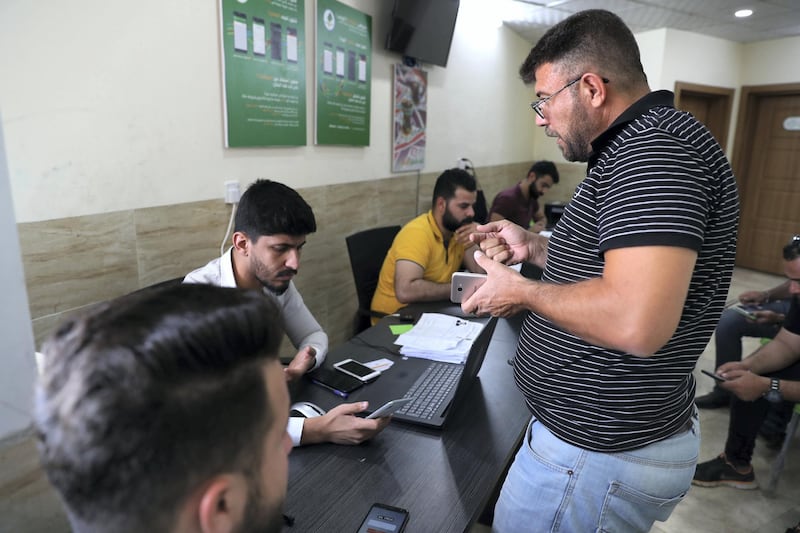

“Iraq has opened up to the world and a lot of Iraqis have been traveling abroad, especially to the [other] countries in the region. Definitely, there was a constituency that knew what Careem was and what Careem did but [it was] a small constituency. IT infrastructure and IT literacy is still quite low in Iraq so what we did is we invested a lot in education and put a lot of people on the ground – promoters, ambassadors – to teach people how to use the app face to face,” says Mr Al Hakim who has been with Careem for over a year and in the country for four and a half.

Those customers they taught how to use the app in turn educated other people in their vicinity, helping to spread awareness of Careem. Mr Al Hakim says they found a market hungry for its services.

“[The] downside is that all the interruptions that we face, how much they actually affect business. Interruptions that are related to infrastructure, for example road closures, interruptions to internet service. They don’t only affect business during the phase that the interruptions take place but also afterwards because you need to build the business back up again.”

Careem’s team of more than 30 on the ground has been flexible and creative in order to find workarounds when there are internet interruptions.

“We have found ways to get around at least the internet cut-offs by allowing people to call a phone number and through booking manually, and we serve people through those hours in the morning when the internet would be cut off,” he says.

"Today marks a key milestone for Careem. Iraq is a country with rich heritage and strategic importance for the region,” - co-founder & CEO of Careem, @MudassirSheikha https://t.co/NHSdXrQUjM

— Careem (@careem) January 15, 2018

Security has obviously been a concern in the country ever since the US-led invasion toppled Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003. Of late, there had been some signs that confidence had returned. Both anecdotally in terms of the stories of a lively nightlife in Baghdad and evidenced by the once-heavily fortified Green Zone’s concrete barriers being taken down at the end of last year, with the area now open to traffic after the morning rush hour.

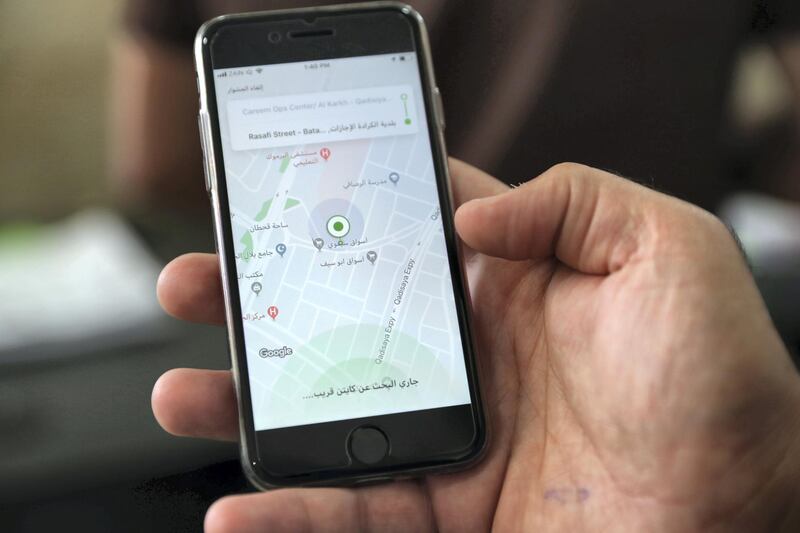

The digital mapping of Iraq has also been under-developed when compared to other countries. Careem has tackled that issue head-on, mapping 15,000 locations so far in the cities that it operates in.

“We physically would go to the roads that were closed and send those co-ordinates to Google. Roads have been opening up lately in the last twelve months or so and we have been mapping the opening of roads again,” Mr Al Hakim says.

As a result, people are increasingly using digital navigation systems.

“If Google Maps reflects the true reality on the ground it means that more people can rely on Google Maps and more people can use the least congested roads to get to work for example, to commute in the morning, because congestion in Baghdad is a huge issue,” he says.

Parking is also an issue in Baghdad, a city with an estimated population of 7 million, with more than half of Careem’s customers are car owners.

Most of Careem’s ‘captains’ – what they call their drivers - used to be taxi drivers.

“The taxi market in Iraq is quite fragmented in general. In Baghdad alone there are hundreds of thousands of taxis. What we did when we came in was we created a community that everyone belongs to. Captains now feel that they have someone supporting them,” he says.

Mr Al Hakim recounts a story of when Mudassir Sheikha, Careem’s chief executive and co-founder, came to Iraq for a visit about six months ago.

One of the captains spoke at a meeting arranged to introduce Mr Sheikha to some of them. He said that when his kids ask him, ‘Daddy what are you going to do today’ and he tells them he will be a captain with Careem, that they look at him with a happiness and pride that was not there when he was a taxi driver for fifteen years.

The anecdote serves to highlight how the company has offered something unexpected for its drivers beyond an earning opportunity.

Careem says that taxi drivers that have joined Careem increased their income, on average, by 30 per cent to 50 per cent.

The level of professionalism set by Careem work both ways.

All captains are required to provide proof of a clean criminal record. They must own the cars they use and show a valid driving licence.

“One of the main reasons why people use us is safety. That’s one of the main value propositions. Especially [for] female customers,” says Mr Al Hakim.

The app’s functionalities also help. For example, you can share your ride with a friend or family member and that friend or family member can track you in real time, he says.

“Because we are a trusted and safe transportation option, we have enabled females to actually go out more and enjoy their lives more. This is an indirect impact that we’ve had [on the economy] and it has coincided with the fact that Baghdad has become safer as a city and it’s opening up. It’s kind of precipitating this change in social life in Baghdad.”

There are no plans to introduce female captains at the moment, however.

Careem’s presence is also helping to support a fledgling start-up ecosystem, says Mr Al Hakim, who has attended a number of events related to the local tech scene.

“For me personally and our team, we see it as a responsibility to our generation and our country to create a success story that inspires people. If you have examples guiding people though a journey and showing how it can be done you will actually help create that success story,” says Mr Al Hakim.

He has been impressed with the calibre of both entrepreneurs and the labour force.

“People always say there is a lack of human capital in Iraq. I disagree. The talent that exists here … people need a bit of guidance but they actually shine.”

The plan is to keep growing but Mr Al Hakim would not confirm which cities will be next for Careem.

“We’re looking to expand to major Iraqi cities and provinces. That is one of our main focuses. There are a few cities we are looking at and we will expand to them in the next few months.”

Iraq is, he believes, “an untapped large economy and a country with great influence in the region both historically and at the moment”.

“We can be an agent of change for the positive. We can touch the lives of many people and create a ripple effect of success stories across the country.”