Dozens of wind turbines each standing 80 metres tall spin in the breeze on the plains of Oklahoma, feeding electricity for a Google data centre about 290km away.

Worldwide, data centres like the Mayes County site outside Tulsa handle almost 32 quintillion bytes of information each day, according to Cisco Global Cloud Index. That’s the equivalent of streaming 32 billion hours of Netflix, and it makes big tech companies some of the fastest-growing energy consumers.

It’s also posing a dilemma for companies like Facebook and Google’s owner Alphabet, whose data hordes - which are expanding at an ever increasing pace as more people join up - are making them more prominent energy consumers at the same moment investors are increasing their scrutiny of their stewardship of the environment. The answer for them is increasingly to line up long-term contracts for green electricity, adding momentum to the shift away from fossil fuels.

“We spend a lot of time chasing renewable energy to match our consumption,” said Neha Palmer, head of energy strategy at Google. “We have 15 data centres that are live, and we’re building out more.”

Cisco expects the torrent of data to increase 75 per cent by 2021 as more things are connected to the internet. Items from thermostats to kettles that once stood alone in households increasingly are linked to the web, creating data in the process that companies like Google are having to manage.

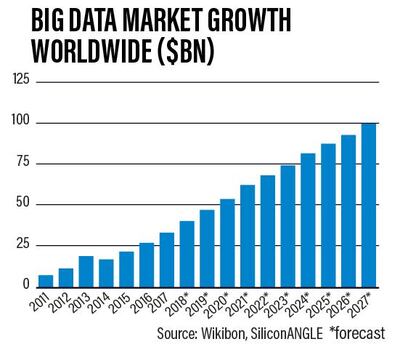

And its a fast-growing market forecast to hit $100 billion by 2027.

Last November, The National reported on the inauguration of the Panorama artificial intelligence and Big Data centre at Abu Dhabi National Oil Company's (Adnoc) headquarters in Abu Dhabi.

Panorama enables the real-time monitoring and analysis across the group's areas of operation using a 50-metre floor-to-ceiling LED screen, which takes up an entire floor in Adnoc's headquarters building.

The centre can provide direct data from Adnoc's operations in exploration, development, production, gas processing, refining, petrochemicals, sales volume, marketing and product transfer to customers around the world, as well as services and logistics.

In addition to the global rise of data centres, the number of connected devices is expected to grow 12 per cent annually, jumping from 27 billion last year to 138 billion in 2030, according to forecasts from IHS Markit. The research group estimates data centres worldwide draw as much as 2 to 3 per cent of electricity demand in developed nations. The International Energy Agency puts the figure at 1 per cent worldwide but says accurate estimates are difficult to make.

Rising power use is a reputational risk for the tech industry, since increasing coal use to feed its server farms clashes with many company’s green ambitions. The incoming wave of data will only boost their energy use and whatever it is that powers those machines will have an impact on greenhouse-gas pollution.

“This infrastructure has a 15 to 20-year lifespan,” said Gary Cook, a senior IT sector analyst and energy campaigner at the environmental group Greenpeace. “If they get powered by coal and contribute to climate change, its going to make it a lot harder to make that transition to renewables sources.”

Google and its competitors are alive to that issue. At the Mayes County data centre in Pryor, about 60km east of Tulsa, halls are lined with blinking servers behind glass doors. They’re transmitting and storing trillions of bytes of information every day from applications supporting Google. Those include Gmail and G-chat messages to photos and videos saved in Google Drive. The power comes from wind farms built by NextEra Energy and Chermac Energy. By signing a long-term power purchase agreement, known as a PPA, Google and companies like it are able to lock in a predictable price for their electricity and guarantee to investors and environmental groups that they’re not increasing coal use. Electricity is by far the primary operating cost for a data centre.

The tech industry has become the biggest corporate buyer of renewables, inking deals for 10.4 gigawatts to date, according to Bloomberg NEF. Several household names such as Apple, Microsoft, eBay and Etsy have set targets to be 100 per cent powered by clean energy. Google said it reached this goal last year. Facebook is the world’s largest corporate procurer of renewables so far this year.

_______________

Read more:

Region's energy players can gain greatly from high-tech adoption

Adnoc's gas master-plan and artificial intelligence to dominate Adipec 2018

_______________

The largest sellers of green power to these companies are NextEra, Invenergy and units of large European utilities such as Energias de Portugal, Electricite de France and Enel.

New web-linked technologies are fanning power demand. Autonomous vehicles, a top priority over at Google with its industry-leading Waymo business, produce reams of data - and energy demand in the process. Sensors and cameras constantly scan a moving car’s environment to make decisions on how to advance, turn and stop. This information is starting to flow through data centres so it can be analysed and sent back to the vehicle in milliseconds, consuming electricity in the process.

More data centres are being built as these needs expand. Google announced earlier this year that it will spend $600 million to extend its facility in Pryor, bringing its overall investment there to $2.5 billion. It’s also planning a facility in the Netherlands. Other major cloud providers such as Amazon and Microsoft have also been investing in recent years to expand these services.

Tech companies are also starting to site their data centres in places with access to green power. Nordic countries are a prime destination, benefiting from rich wind and hydroelectric resources and also cooler climates that save on air conditioning for hot servers. Facebook has a facility in Lulea, northern Sweden, where it’s expanding to bring its total investment to about $1bn.

Energy companies are eyeing data centres as a key source of new electricity demand. Power consumption has been relatively flat in western Europe as a result of efficiency measures, but the tech industry is set to have a significant impact, according to Andreas Regnell, head of strategy at Vattenfall, Sweden’s largest utility.

“In the near term, I think we will probably see data centres as the biggest driver of power demand, at least in the Nordics,” Mr Regnell said.

While the vast server halls are getting larger, they’re also getting more efficient. The surging flows of information could potentially be handled with better technology that uses less energy and offsets some of the rise in power consumption that’s expected, according to Jonathan Koomey, a lecturer at the School of Earth, Energy and Environmental Sciences at Stanford University.

“On one hand you have a rapid increase in computation, data transfers and number of computations,” Mr Koomey said. “But on the other hand you have improvements in the efficiency of these computations. Operators are figuring out ways to deliver more computing using the same or less energy.”

The energy generated from solar and wind farms is matched to the tech companies’ power use, but it seldom actually powers their hardware. They sign what’s known as a virtual or synthetic power purchase agreement, where the electricity from the renewables project feeds into the grid which the data centre is also hooked in, but the distances are typically so great that the actual electrons will be consumed closer to the wind or solar farm.

“When we say we’re matching our energy, we mean that for every terawatt of power that we consume at Alphabet, we’re matching that by a physical terawatt hour that’s being generated somewhere else,” said Mr Palmer. “We are looking at ways on how to match our actual consumption.”