Last Friday, Lebanese lucky enough to have electricity could, assuming they could rise from their heat-induced torpor, enjoy the opening ceremony of the London 2012 Olympic Games.

It was an opportunity, for a few hours at least, to forget the power cuts, industrial action, refugees crisis and sectarian tensions that have gripped Lebanon for much of what has been a pitiful summer.

And it's only August 2 …

The Lebanese prime minister Najib Mikati, no doubt taking a respite from another kind of heat, was in London to applaud Lebanon's 10-man team, which made it to the games with little or no government support, and to tell them they could teach our politicians a thing or two about sport and life.

The Lebanese judo team did this with gusto by demanding a barrier be erected between it and the Israeli squad during training. So much, then, for the exhortations of Britain's ambassador to Lebanon, Tom Fletcher, who promised the games would be "a great unifier".

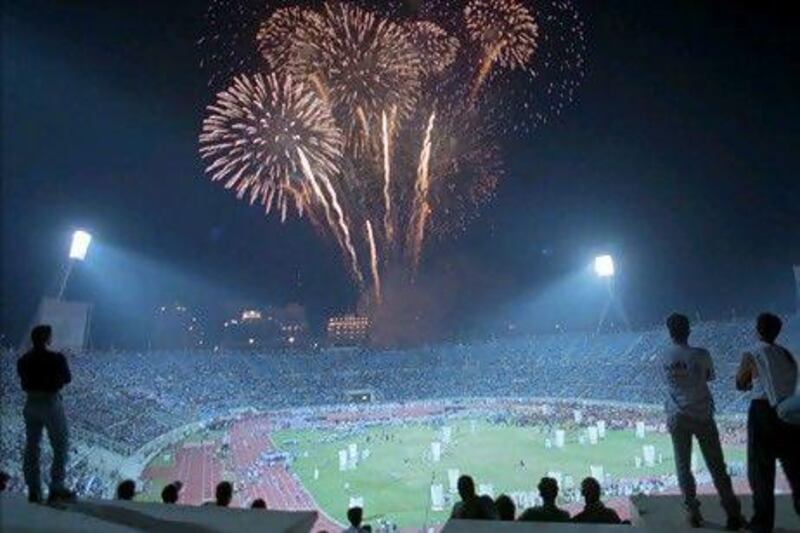

Amid all this excitement, I found, apropos of nothing in particular, my press pass for the 8th Pan Arab Games, which were held in Beirut in July 1997. Wikipedia reminds us that "3,253 athletes from 18 countries participated in events in 22 sports", while more than 50,000 people attended the opening ceremony in the newly built Cité Sportive on the southern outskirts of the city.

Back then, Lebanon was riding a wave of post-war bullishness with then prime minister Rafiq Hariri still very much the force behind Lebanon's reconstruction boom. There was optimism in spades and the president Elias Hrawi delivered a stirring speech at the opening ceremony in which he assured the world, "The Lebanese have returned to their heritage and unity, they have returned to build a Lebanon for heroes, youth and peace."

Fifteen years on there is very little unity - the fighting in Tripoli and the tension on the streets of Beirut are testament to this. The heroes to which he was referring do not exist - the mountaineer and explorer Maxime Chaya is the only genuine contender - while our youth gets out on the first available plane to the Arabian Gulf, where there are a few more jobs than at home. And peace? Well I guess peace, like unity, is an elastic concept.

So, what went wrong? I would posit it's a two-tier thing. First, quite simply, we are not a "whole" society. This is reflected in our economy, which is made up of a concentration of high value, short-term activities such as banking, property development and, when the going is good, tourism. In the meantime, we neglect long-term, job-creating sectors such as manufacturing, technology and agriculture.

When it comes to education we eschew the humanities to concentrate on what we believe are the more muscular disciplines such as medicine, engineering and law. Those who fail to make the cut study business. The result is that we end up top heavy: too many professionals; and not enough thinkers and creators. Those artists, athletes and entertainers we do throw up are viewed, often with suspicion and apprehension, as curiosities because they don't fit into our narrow paradigm

The roots of the second tier of the problem can be seen in the debacle in the London judo hall and the Lebanese obsession with Israel, a cause into which an unhealthy amount of Lebanon's resources - human, financial and natural - have been channelled with very little to show in return.

Lebanon's judo team will be remembered less for the prowess it brought to the mat and more for, once again, bringing politics to an Olympic Games - this one determined to show right from the start it was about all things positive and good, a celebration, not just of London and Britain but also of what little there is of global unity.

As usual, we struck the wrong note.

Michael Karam is associate editor-in-chief of Executive, a Lebanese regional business magazine