As the Fifa World Cup in Brazil kicks-off next month, football fans in the Middle East are also looking forward to what could be the first global sporting event to be staged in the region — set to take place in Qatar in eight years time.

The Qatar 2022 World Cup promises to be one of the most controversial in the event’s long history already prompting concerns about the extreme summer weather, allegations of nefarious activities around the bidding process and “subhuman” working conditions for labourers. Some even have concerns the competition will eventually be have to be staged elsewhere.

When Fifa, football’s world governing body, voted in 2010 to make super rich but tiny Qatar the smallest country ever to host the World Cup rather than rival bidders the United States, Japan, South Korea and Australia, the decision provoked huge controversy.

Rivals complained Qatar had little history of footballing success or interest, that with average summer temperatures of more than 40°C, the country is too hot to stage the prestigious competition in the summer, that Qatar had few existing stadiums or other infrastructure to stage the event and that the country would not be able to provide the sort of sporting legacy from the event the rivals could.

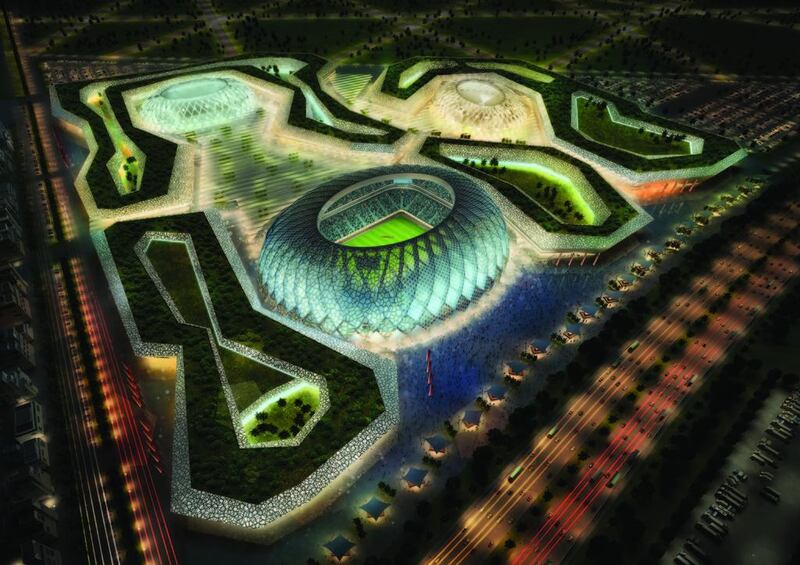

In its World Cup bid, the Qatari authorities pledged to provide 12 new stadiums, use cutting-edge technology to cool them, spend more than US$200 billion upgrading infrastructure in preparation and provide a lasting legacy felt across the world.

Qatar’s promised infrastructure spend included shelling out $34bn on a rail and metro system, $7bn on a port and $17bn on a glitzy new airport as well as $3bn to be spent on building nine new stadiums and renovating three existing ones and building 84,000 hotel rooms.

According to Harold Mayne-Nicholls, the author of the slick Fifa bid evaluation report published in 2010, Qatar also showed “a strong commitment to having a carbon-neutral Fifa World Cup”.

This was demonstrated not only with its plans to use environmentally-friendly cooling techniques in the new football grounds and high-quality grass grown under sun shades but also with its ingenious plan to ship modular sections from the stadiums to developing countries to construct 22 new venues after the event.

“The construction of the 22 modular stadiums abroad after the event as well as the domestic initiatives are important,” Mr Mayne-Nicholls said at the time.

The bid also included wider social aspirations including establishing non-elite football structures for grassroots football, to involve women, expatriates and people with special needs, new tournaments providing social integration for non-nationals in Qatar, talent scouting in Thailand and Nigeria, support for schools in Nepal and Pakistan and support for football programmes in refugee camps in Syria.

But, four years down the road, in Qatar things are looking a little shaky.

Bureaucratic and planning problems have meant many major infrastructure projects have been slower to get started than anticipated.

According to Qatar’s finance ministry, during the financial year that ended in March 2013, government spending rose by just 2.2 per cent to $48.9bn — the first time the government has undershot its budget plan since 1990 — as the country struggles to get such huge and complex infrastructure projects underway.

Qatar's Hamad International Airport, the country's long awaited $17bn facility capable of handling 30 million passengers a year in phase one, finally opened on Wednesday, six years behind schedule and more than $1bn over budget. The new airport suffered from a series of delays that resulted in a legal row with the interiors contractor Lindner Depa.

Work started later than expected on the metro system, too, with four design and build contracts worth about $8.2bn for phase one of the Doha Metro finally awarded last year, while ambitious plans to build road bridges to link the country to both Bahrain and the UAE appear to have been kicked into the political long grass.

Then, in Doha last month, Ghanim Al Kuwari, the organising committee’s senior manager for projects, made a startling revelation. He said Qataris had reduced the number of stadiums they planned to build to host the event from an original 12 down to just eight amid rising costs and delays.

Construction has started on the Wakra stadium, while work on the Al Rayan stadium is set to start later this year, or early in 2015, Mr Al Kuwari said. He did not say what effect the move to reduce the number of stadiums would have on Qatar’s legacy plans.

This retrenching comes after last year Fifa president Sepp Blatter launched a consultation process over whether the football showpiece should be moved to the winter so the country’s extreme summer heat would not “endanger the health” of “players or fans”.

Yet, as the event draws inexorably closer, more and more organisations are questioning what sort of legacy the Qatar World Cup will ultimately leave. Last year the UK’s Guardian newspaper published allegations that 44 Nepalese workers had died in Qatar between June 4 and August 8 last year, half of them from cardiac problems and workplace accidents. It claimed it had found evidence of forced labour on a major World Cup-related infrastructure project and that some Nepalese workmen had not been paid for months and had their passports confiscated by employers. The newspaper said the workers faced “exploitation and abuses that amounted to modern day slavery”.

The allegations were quickly denied by both Qatari and Nepalese officials in Doha.

Last week, the general secretary of Fifa said he wanted an investigation into allegations regarding Qatar’s selection to host the 2022 World Cup completed before the start of this year’s tournament in Brazil.

FIFA’s Jerome Valcke urged the former US attorney Michael Garcia, the Zurich-based body’s chief investigator, to announce results of his probe before the first game on June 12.

Qatar has always said it acted properly throughout the process.

Separately, the Qatar World Cup’s financial legacy has come under scrutiny.

In March, the IMF warned that costs for the ambitious building programme was also at risk of snowballing leaving an uncertain financial legacy.

“Qatar will continue facing the risk of cost escalation given its commitment to a compressed timetable ahead of the 2022 Fifa championship,” the fund wrote in a report.

“The programme entails the possibility of overheating in the near term, and low return and overcapacity in the medium term. In particular, the extent to which public investment will durably boost private sector productivity remains uncertain.”

And experts warn that rising costs are likely to occur at the same time that Qatar’s revenues from its main export, liquefied natural gas, decline.

“We expect Qatar’s fiscal surpluses to narrow considerably during the next several years as liquid natural gas earnings stagnate, but costs associated with large-scale development projects will continue to mount,” says the IHS Middle East economist Jake Jolly.

There is, it seems, a good deal of grass to be covered before the first whistle blows in 2022.

lbarnard@thenational.ae

Follow us on Twitter @Ind_Insights