Years ago – well, two to be exact – it seemed most people were not too concerned about how secure their everyday digital communications were.

Okay, we did not give out our email address or mobile number to just anyone and, while we might have overshared a little on social networks, we were content in the knowledge that it was only our friends who could see what we posted.

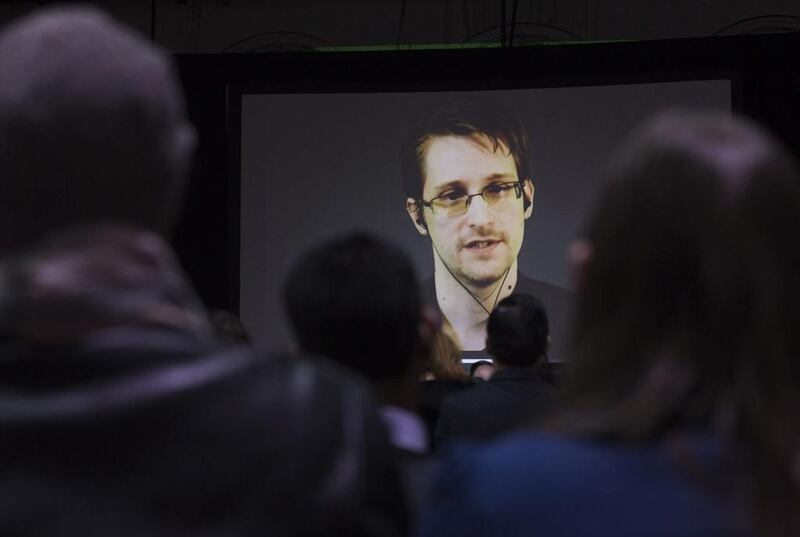

That all changed in early 2013, when a young US national security agency contractor (NSA) called Edward Snowden asked the UK Guardian newspaper journalist Glenn Greenwald to download encryption software so they could communicate securely about a story that he might be interested in. The rest is history.

The extent of the US government’s monitoring of private communications under the NSA’s Prism surveillance programme has since made everyone – criminals and law-abiding citizens alike – a bit more wary about how secure their communications really are.

In response to the Snowden revelations and growing public concern, technology firms are getting increasingly serious about the encryption of everyday voice, video and text communications, rolling out new encryption controls on voice and messaging services that make the monitoring of everyday communications almost impossible.

Governments are becoming more uncomfortable about what the security implications of such services are.

June of last year, BlackBerry launched BBM Protected, offering several additional layers of encryption to its popular instant messaging service.

Even more significant was the announcement by WhatsApp in November that it was integrating Textsecure, a piece of software developed by noted cryptographer Moxie Marlinspike, into its Android messaging app, with versions for iOS and other platforms in the works.

The integration of Textsecure means all WhatsApp messages sent from the updated app will be encrypted end to end, making it virtually impossible for anyone, be they security agencies, hackers, or even WhatsApp itself, to monitor everyday communications (although hackers this week claimed that it was still possible to bypass its privacy).

"WhatsApp deserves enormous praise for devoting considerable time and effort to this project," said Marlinspike in a blogpost at the time.

“Even though we’re still at the beginning of the rollout, we believe this already represents the largest deployment of end-to-end encrypted communication in history.”

Last year also saw the global launch of Blackphone, an Android smartphone that offers users the ability to make calls and send and receive texts without being monitored.

Developed by the encryption specialist Silent Circle and the Spanish phone maker Geeksphone, the handset comes pre-installed with PrivatOS, a stripped down, ultra-secure version of Android and comes with a series of apps that offer secure messaging and voice calls.

“If someone sits behind you on the bus and looks at what you’re reading, it makes you deeply uncomfortable,” says the Blackphone chief executive Toby Weir Jones.

“The difference now is that it’s possible for people to look over your shoulder from half way around the world without you noticing. Ultimately we believe people should be able to notice that and to be able to choose to do something about it.”

Mr Weir Jones says take up of the phone worldwide has been “outstanding” but declines to give further details.

Blackphone announced a deal with the Dubai-based Big On Telecom in October to distribute the handset across the Middle East and Africa, targeting government and enterprise customers. Big On Telecom’s chief executive Ramzy Abdul-Majeed said that the handset would retail for approximately $700 (Dh2,600) when launched, declining to say when that would be.

While private means of communications such as Blackphone are not a new phenomenon, the increased availability of such tools for the mass market have proved discomforting for many governments and security agencies worldwide.

A senior official at the US justice department recently accused Apple, which introduced end-to-end encryption on its iMessage service in 2011, of putting lives at risk with its enhanced encryption messaging protocols.

According to reports in The Wall Street Journal, officials presented a hypothetical scenario of a child's kidnapping where authorities would be unable to monitor criminals' communications. Last month the UK prime minister David Cameron announced plans to clamp down on encrypted messaging services, to try to deny terrorists a safe space to communicate online, days after the head of the British security service MI5 warned that intelligence agencies were in danger of losing their ability to monitor "dark places" on the internet.

"The question remains: are we going to allow a means of communications where it simply is not possible to do that?" said Mr Cameron in a speech in Nottingham, days after the fatal shootings at the offices of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in Paris.

“My answer to that question is: no, we must not. The first duty of any government is to keep our country and our people safe.”

Such questions and concerns are surely on the radar of governments and regulators in the Middle East. The UAE came close to outlawing BlackBerry’s BBM messaging service in 2011 over concerns about lack of access to the company’s messaging servers.

The Telecommunications Regulatory Authority did not respond to requests for comment for this article.

“If the likes of the UK and the USA are making noises about cracking down on such services or watering them down, then I think we can expect the UAE [and] other states to be considering a similarly tough line, if we recall what happened with BlackBerry,” says the UK-based computer security expert Graham Cluley.

A blanket crackdown on services such as WhatsApp and iMessage would have little impact on efforts to monitor criminal communications, says Mr Clulely, as other secure means of communications were readily available elsewhere.

“The people who would most be inconvenienced by a blanket ban would be the people who are doing nothing wrong,” he says.

“While such people may find that their favourite apps are no longer available, any person who’s up to no good will find it very easy to download software from elsewhere on the internet that will have the same effect.”

The increase in privacy enhancing communications tools is not one that can be easily put back in the box, according to Mr Weir-Jones.

“WhatsApp is just the latest example. It’s part of a general transformation that has been going on for pushing 30 years now,” he says.

“We don’t believe that this general tide is reversible.”

jeverington@thenational.ae

Follow The National's Business section on Twitter