It’s Monday, morning, you’re just back from your annual leave – don’t dare say holiday – and there’s this bombshell in your inbox: “We really need to push the envelope so let’s diarise a thought shower before close of play and cascade the learnings.”

Your line manager has reached out to you, evidently keen on “actioning some key deliverables asap”.

Have you been making enough hay? You’d better find a window for some bleeding-edge, blue-sky, out-of-the-box thinking and make darn sure everyone ends up singing from the same hymn sheet going forward because if you don’t, there’ll be some blamestorming.

There could be some change management going on. You may get transitioned out of the company, backfilled by some of the recent fresh-faced onboardings.

Confused? Possibly not.

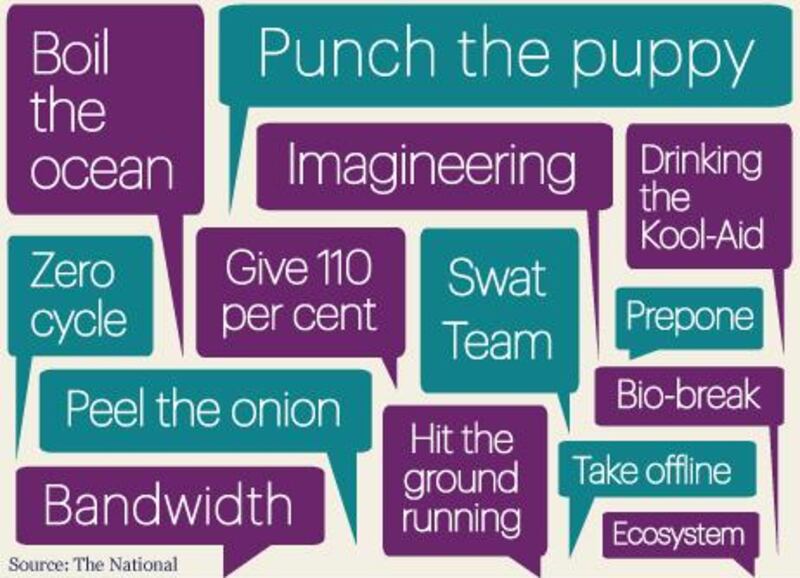

Office jargon is so widespread many people no longer realise they're using it, unless they're confronted with the more outlandish terms such as "let's open the kimono" or "drink the Kool-Aid", or this reporter's favourite, "punch the puppy" (see glossary here).

Many of these terms originated in the field of "business theory" in America in the 1950s and 1960s, says the British journalist and author Steven Poole, who has written a book on business speak called Who Touched Base In My Thought Shower?

But some words go back much further. “Ideation”, a fusion of thinking, planning and solving – or, more simply, having ideas, was first used in the 17th century. Today, companies have managers in charge of whole ideation departments.

Poole was inspired to write the book after penning an article about the phenomenon for the United Kingdom's Guardian newspaper.

“I was surprised by the number of passionate responses by commenters trapped in offices where everyone talked like this and who really hated it,” he says.

“So I decided to write a book in solidarity with the rhetorically downtrodden.

Not all the phrases are bad, Poole admits. Some pieces of jargon are just vivid images or useful shorthand. “I learned recently that instead of saying, ‘Let’s kick this into the long grass’ [meaning put it aside and think about it some other day], one can just say ‘Let’s long-grass it.’ That seems quite efficient.”

But many of the terms are euphemisms designed to make managers look clever, or blameless, or in control. So job cuts become “resizing” and “rationalisation” and problems are “issues” or “challenges” – because an outright problem is something they might get blamed for.

Office speak reflects the preponderance of men in management positions, with a plethora of macho military terms. But oddly, it is also peppered with terms that seek to avoid all confrontation.

Some managers refer to “weaponising” their business processes, meaning to make them really good, ie capable of blowing the competition out of the water, presumably. But, by contrast, the word “about” is out of vogue these days because it’s too direct. Instead, one meets to talk “around” issues, or “around” underperforming human resources that need to be moved on to other challenges within or preferably outside the company.

Euphemisms are found for the simplest concepts to make the mundane seem exciting, glamorous and devilishly clever. To “drill down”, “deep dive” or “go granular” means to look at something closely. Everything is “key”. Things are not merely done, they’re “actioned.”

“It’s harmful to the extent that it exists to deflect blame away from bosses, to dehumanise workers, and to obscure the real source of problems,” Poole says.

Asked to provide a favourite term, he says: “I was especially alarmed by the idea of ‘creative abrasion’, which sounds like it would give you a rash or worse. Meanwhile, a friend forwarded me an email the other day in which the workers were informed that some technical thing wasn’t working because of ‘overrunning back-end processes.’”

But is it really the jargon that people object to, or is it the working environment reflected by that language?

Office jargon usually stems from a culture of domination, dependence and sycophancy that is part of everyday life in countless workplaces. Staff have to maintain good relations with colleagues and especially superiors even if they disrespect or loathe them. And managers have to pretend they know what they’re doing when sometime, in fact, they’re stabbing in the dark working in industries that are ever more complex and volatile.

Managers in the “wheelhouse”, busy “hypervising” operations (a step up from “supervising”) will be flattered to be asked for “air cover” on decisions taken by their subordinates. They might even condescendingly “empower” their staff to perform certain tasks.

Jobs no longer get “outsourced” – that sounds too negative – they get “rightshored” meaning moved to places where they should have been all along. And naturally there is a term for employees who are constantly on call thanks to laptops and smartphones – they’re “moofing” (meaning “mobile and out of office”).

Professor Jo Angouri, who researches workplace communication at Warwick University, says office jargon often mirrors changes in the workplace many employees don’t like, such as the radical erosion in job security in the wake of the financial crisis, ever-faster changing job roles and the introduction of new forms of assessment to measure the performance of employees.

“It’s not necessarily the word per se that someone is reacting to, it is basically what it means,” Prof Angouri says. “The issue often is not annoyance at terms such as being ‘relieved from their duties’, the issue is that job contracts are less permanent and people see themselves and their skills as being increasingly commodified. People react if or when they feel that they are not valued as individuals.

“I don’t call it jargon. I call it language. Workplace changes shake the status quo, and that is manifested and done in and through language.”

Scores of office terms make people groan. Some are so exaggerated they surely can’t have meant to be taken seriously. Try saying “Let’s meet for a thought shower” with a straight face.

“Thought shower” has replaced the less politically correct “brainstorm”, which might offend people with brain disorders, apparently.

One website offers a Business Buzzword Generator that spouts out random phrases for a company’s core strategy. Many look so plausible they could credibly reeled off in board meetings. How about “adaptive enabled awareness alignment?” Or “client-centric market-driven feedback touchpoints?”

Imagine the impressed nods around the boardroom table if you pepper your power-point presentation with those. Obfuscation can enhance your power and deflect criticism.

Will there ever be a revolution? Will staff rise up and force their employers to stop using jargon? It’s unlikely. If anything, business speak is spreading as public administration increasingly embraces efficiency-enhancing private-sector principles. Bureaucrats these days like to sound like chief executives.

Prof Angouri says business speak is likely to be here to stay because it describes changes in the real economy. Another reason, says Poole, is that too many people are invested in it.

“For years, surveys have shown that, although everyone claims to despise business jargon, most people also can’t avoid using it themselves, because that is how you get taken seriously. And as long as management courses keep teaching it, it will unfortunately stay around,” he says.

But what about normal language? Will it suffer if we spend our working lives talking business babble?

“I think that the glorious English language herself is, happily, robust enough to tolerate any amount of abuse by mendacious Machiavels,” says Poole.

So, team, let’s get on board with it. Let’s have a town hall meeting to workshop some new phrases, and reap the synergies.

It is, to use another military term meaning to tell your staff something, time for a heads-up.

business@thenational.ae