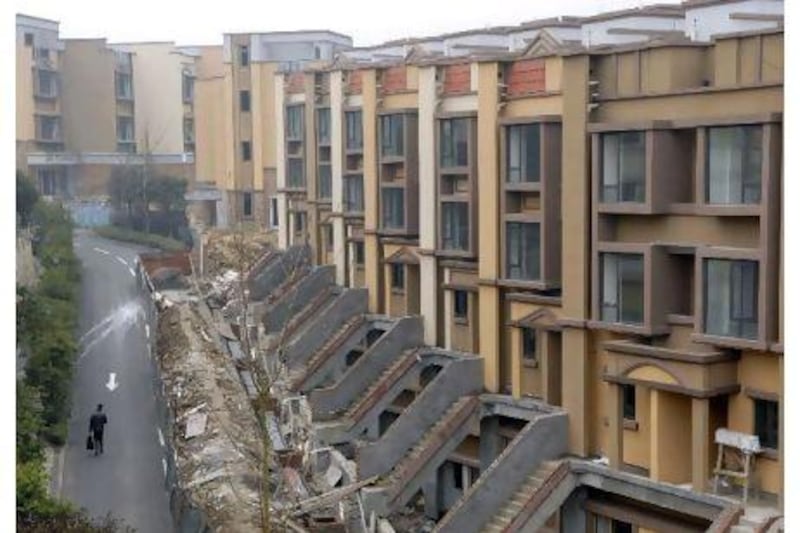

Blocks of apartments are going up by the dozen in countless major Chinese cities.

From Shanghai to Tianjin, from Beijing to Chengde, and from Taiyuan to Chongqing, they are sprouting at a rate that puts even Doha's frenetic building spree into perspective.

While for countless millions, these represent an escape from the traditional single-storey houses that had fallen into disrepair, the reality that prices have risen as fast as the tower blocks means many other people are left out in the cold.

Zhao Yan, 27, works in Beijing for an overseas pressure group and is among those daunted by the prospect of taking their first steps on the housing ladder. Property - and how difficult it is to buy - are, she says, a regular topic of conversation among her peers.

"For the young generation, without any support from their families, it's very difficult to purchase real estate in Beijing," she says.

Difficult is putting it mildly. Property in Beijing costs an average of 23,000 yuan (Dh12,848) per square metre, 25 per cent more than last year, according to the China Index Academy.

"Many of my friends rent in Beijing. Finding their own apartment is not really that common for people of my age," Ms Yan says.

"There are friends [who own their own apartment], but a lot of them purchased several years ago, when the price was cheaper, and had family support."

China's property boom has been described as "a treadmill to hell" by the US hedge fund manager James Chanos, although there are few signs yet that the bubble many say has been created is about to burst.

Figures for 70 major cities released in January by the National Bureau of Statistics of China showed house prices dropped in just two locations last year, while many other locations saw double-digit increases. For the many who have moved from decrepit government housing to shiny new apartments, it is good news. Yet the Chinese authorities at the highest level have indicated they realise there is a problem for those who remain locked out.

Wen Jiabao, the Chinese premier, said this month the government would "firmly curb the excessively rapid rise in housing prices", and over the past 18 months multiple measures had been introduced with that in mind.

The authorities have told banks to increase down-payment requirements and lending rates, with those buying multiple homes targeted especially. Banks have been instructed to restrict lending to developers. Yet apartment prices have continued their inexorable rise.

Commercial property, too, is growing in value rapidly, with Soho China, one of the country's most prominent developers, recently predicting "a significant increase", as the sector is largely immune to the measures introduced to cool the housing market.

To get around the high prices of apartments, affordable housing schemes have been set up where, in some cases, developers have sold off certain properties at below-market rates in return for being allowed to sell others at their full value. However, there have been complaints that many aspiring buyers feel qualifying for these schemes is difficult. Further measures to control price rises therefore appear essential.

In January, the much talked about property tax was finally introduced to parts of Shanghai and Chongqing, with owners expected to pay a levy for owning a property, rather than purchasing one. The hope is this will deter speculative purchases and give local authorities an alternative income to the land sales that have generated so much of their revenue and helped to drive the property boom.

Xie Xuren, China's finance minister, said a week ago the tax was not about to be rolled out nationwide, although the authorities have talked of this as an ultimate aim, if the current trials prove successful.

The clampdowns on housing speculation and other measures to cool the market have "frozen up demand, frozen the housing market", says Ren Xianfang, a China analyst at IHS Global Insight in Beijing.

"That will hopefully give the government some time to adjust the supply side," she says, referring to concern there were not enough units to satisfy the pent-up demand.

Others see the solution as more fundamental than building more flats, of which there are already about 3 billion sq metres under construction, plus about half a billion sq metres of commercial property and a smaller amount of office space.

The key is to provide alternative investment opportunities to property, says Patrick Chovanec, an associate professor at the school of economics and management at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

"Without allowing Chinese people to invest abroad, I don't know how you get out of this situation of all this capital being bottled up in China, with nowhere else to go. You need to give people alternatives to real estate," he says.

"You can put new restrictions on their ability to [invest in property] but if it's the only alternative allowed, they will find ways to do that." Another key factor, he says, is the vast amount of liquidity in China, with the money supply having increased by half in the past two years.

"If people are using real estate to stash their cash … there's that much more money to stash," he says.

While there are measures to tighten liquidity, such as multiple interest rate rises, with more expected, the central government is still aiming for rapid economic growth.

"They say they want to tighten the money supply, but they want 8 per cent GDP growth," says Prof Chovanec.

"If you rein in credit-fuelled inflation, you end up reining in some growth. It's not clear which of these will win."

Also, some promised measures to prevent property speculation, such as ensuring many state-owned enterprises stop investing in property, have yet to be enforced, Prof Chovanec says. Not surprisingly, some wonder if there is the political will to risk jeopardising growth by clamping down too hard on the market.

Apart from discussions of what should be done to cool the property sector is the question of whether the market has created a bubble that may burst - the "hell" Mr Chanos talked of.

The high price-to-income ratio may suggest a bubble exists, says Ms Ren. However, given that many apartments were purchased for minimal cost a decade ago as the government privatised the housing market, she believes the conditions in China may not be comparable to those in other countries. What may be a bubble elsewhere, she says, may not be one in the dragon economy.

"Many families owned homes without any debt because the government gave them out," she says. "This is a situation we've not seen anywhere else in the world."