Munib Al Masri has been called a lot of things over the past six decades — the Duke of Nablus, the Godfather of Nablus, the Palestinian Rothschild — but there is only one name that sticks in the Palestinian tycoon’s craw.

“Just please, don’t call me a billionaire,” he says, “I’ve worked hard in my life, really hard, and I have been lucky. That’s all.”

It is important to Mr Al Masri, at the age of 80, that he isn’t seen as a man that has made his billions as the Palestinians have languished under nearly half a century of occupation by Israel.

He may be chairman of Padico — the investment holding group that controls 35 companies across a range of sectors in Palestine — but he is keen to stress that he has never made any money at home. His fortune was made through the Edgo Group, a global energy conglomerate that he founded and managed from London.

“All my money I made overseas and I brought it back here,” he said.

Al Masri’s palatial house sits on a hilltop overlooking Nablus and opposite the hill that was once his family home. He built Beit Felasteen (Home of Palestine) during the second intifada, after returning to Palestine from Britain in 1994 after the Oslo Accords. On his return, he was one of 200 wealthy Palestinians to start Padico, each of them putting in US$1 million as start-up capital.

The investment conglomerate is now made up of 35 companies across a range of sectors, including telecoms and construction, although 30 of those firms are inactive, he says, due to the Israeli occupation. And while a businessman, Mr Al Masri claims to spend 12 hours of his 20-hour working day engaged in politics.

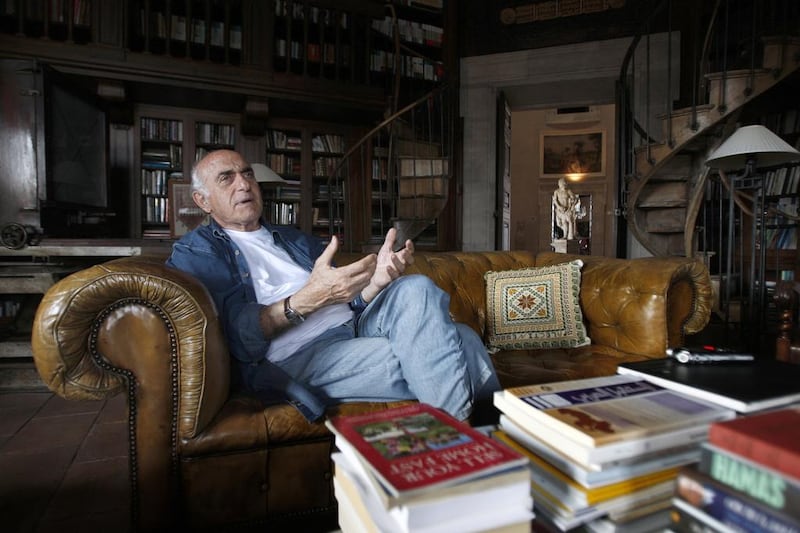

“Almost 60 years of my life I have been devoted to this,” he says, sat in a chair in a reception that he half-jokingly refers to as his “war room’. His mobile phone rings constantly, and every 10 minutes or so a young man in a sharp suit brings him bits of paper to read and sign.

A former confidant of Yasser Arafat — he served in his cabinet during the 1990s and was in Arafat’s compound until just hours before the former leader was flown to the Paris hospital where he died — Mr Al Masri has seen many peace efforts come and fail. But he is positive about the current talks between Mahmoud Abbas and Benjamin Netanyahu and brokered by John Kerry. He also believes it is Israel’s last chance.

“I see a big tsunami coming, a volcano, and people have to realise that enough is enough. We have an opportunity with Obama and Kerry, Abbas and Netanyahu — these are people who could really do it. I see darkness coming if it doesn’t happen,” he says.

“I see people sitting down and saying that we will stay what we are and have peaceful resistance. Or to say we will march. People are very tired. We cannot keep our peaceful attitude. I hope it will not become violent, but you never know,

“We are almost the same number — they are 6 million, we are 5 million living in the same part of this world. We cannot finish each other — we are destined to live together.”

Mr Al Masri warns that Israel risks becoming a third-world economy if it does not use the continuing US-sponsored peace initiative and give the Palestinians their own state. The growing boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS) movement, which he supports, is gaining momentum, and he says Israel could end up being the next South Africa.

“I think the Israelis would be short-sighted to think that time is in their favour. It is the story of South Africa. You cannot hide the sun with your finger. It is becoming apartheid, people are realising this. You cannot occupy forever. Everything they have done since 1967 is illegal,” he says.

Steering Mr Al Masri back onto business is not easy, not least because he does not believe that the Palestinian economy — let alone its companies and markets — have any chance without independence. Although he launched the Breaking the Impasse (BTI) initiative in 2012 — which brings together Israeli and Palestinian businesspeople in an open discussion forum — there is no business element to it.

“There is no economy as long as there is occupation — all that we do is artificial. We don’t have a port, we don’t regulate, we have checkpoints. If there is no free movement of goods and services you can’t make it. You have to have your own port, you have to have airports, your own borders,” he says.

That said, Padico — which celebrates its 20th anniversary this year — has had its successes. It now accounts for up to 27 per cent of the Palestinian economy and employs hundreds of thousands of people. This summer, he says, an investment conference in Palestine will aim to launch an investment fund to bring in foreign capital.

Once again, Mr Al Masri feels the need to stress that he does not make any money from Padico. All of his profits, he says, go into his charitable foundation, which is carrying out work across the West Bank, including building a substantial mosque just metres away from his front gate.

And new projects are not the only thing that Mr Al Masri is involved in. While he was building Beit Felasteen he was surprised to come across pieces of ancient pottery buried in the hillside. He invited an archaeology team to come in on the project, but as he was building at the height of the intifada, he restricted digging to the middle of the night lest the Israelis noticed the work.

“I was terrified that he would uncover Jewish artefacts, in which case they would have almost certainly stopped the project and occupied the site,” he says.

In the end, the pottery turned out to be from the ruins of a fifth century Christian monastery, which Mr Al Masri has had fully restored and now occupies the entire ground floor of his home. Next to the monastery is a museum, which houses other artefacts from the Byzantine, Roman and Islamic periods.

Showing us around the museum, the 80-year-old is more like a schoolchild than an octogenarian: “Isn’t this the icing on the cake?” he says, leading the way across walkways that dissect the ancient site.

Mr Al Masri returns to his calls, his letters and his emails. He admits he is nervous — nervous about the rumours that the talks are failing, nervous about the “darkness” that he sees should that happen. Nervous too for Palestine and Israel, who, he says, as the children of Abraham, should be friends, not enemies.

“I wish I could sit down with Netanyahu,” he says, frowning, suddenly frustrated. “I think if I could talk to him,” he adds, almost under his breath, “I know I could convince him”.

business@thenational.ae

Follow us on Twitter @Ind_Insights