Imagine a two-hour meeting, a dozen points of view, and zero new outcomes. Why meet at all?

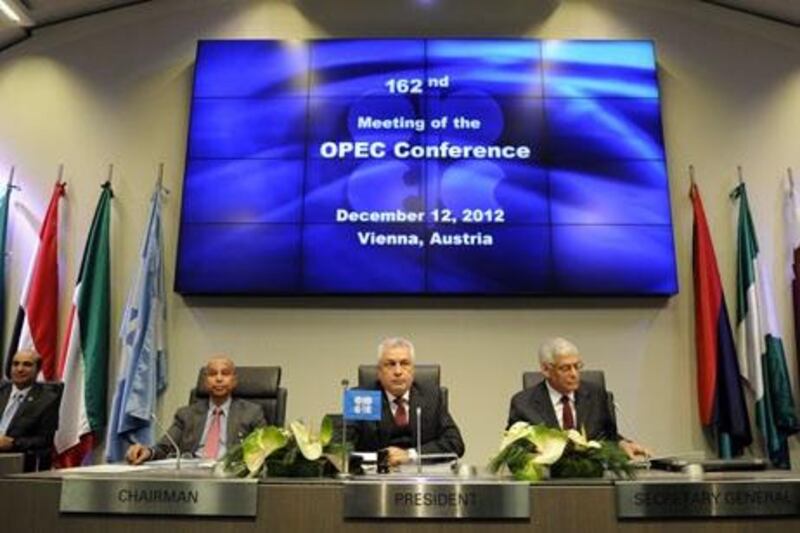

This week Opec ministers in Vienna opted to keep the group's year-old production quota and the current secretary general for an extra year, after failing to reach consensus on a new nominee or the criteria for selecting one.

The lack of decision came at a delicate moment.

The group has cast itself as a benign central banker for the world's crude, ensuring energy and economic stability with its 40 per cent share of global supply.

But Opec's influence over the world's energy supply is threatened today by a rise in North American resources, as well as a potential long-term shift towards cleaner forms of energy such as solar and wind.

Add to that the headwinds of a perilously slow global economy, a need for high oil prices to pay for ambitious spending programmes designed by oil-producing nations, and political disruptions inside Opec from a resurgent Iraq.

"There is a fine balance between all these factors: on one side the increase in production, on the other side the geopolitics, on the other hand the health of the world economy," says Alirio Parra, a former oil minister of Venezuela. "For now there is a balance, but that will not last forever."

Those who have seized on Opec's failure to decide on a new leader as a sign the group is somehow weaker than it once was are wrong, however. Not being able to agree on a new secretary general is just part and parcel of the group's makeup.

"Historically this happens over and over and over again," said Mr Parra. "It doesn't mean that Opec is weaker or that it's indecisive."

"Many are making a mountain out of a molehill," said Michael Rothman, the president of Cornerstone Analytics, an American firm. "The difficulty being witnessed is actually more normal than not which has been the case for the better part of the past 30 years."

Recall the history of Abdalla El Badri, the Libyan official who was kept on for an extra year this week after already serving his two-term limit. Today praised for his finesse in ushering ministers to agreement and his extensive knowledge of markets, he was a surprise selection when he was first tapped to lead Opec in 2006.

"He was plucked out of a hat," says Mr Parra, now of the CWC Group in London. "He wasn't even a candidate until 10 minutes before he was elected."

The choice to keep him on can be interpreted less as a failure of the organisation's cohesiveness and more as a vote of faith in Mr El Badri.

"To clinch it, El Badri has kept prices above US$100, so what more do you need?" asks Nordine Ait-Laoussine, a former Algerian oil minister who today heads Nalcosa in Geneva.

Naysayers point to the fact that the organisation did not take action on how to maintain market share in the face of growing American shale oil and gas production. Members are currently producing 1 million barrels more oil than the world is projected to need next year, and many analysts say Opec will have to lower pumping levels to make room for new American production or risk a fall in prices.

But America isn't the only risk factor, says Mr Rothman.

"There are more than 80 moving parts to the non-Opec equation, and the attention being lavished on the growth in US output seems to be matched by the lack of attention on the collective decline in the rest of non-OPEC output," said Mr Rothman. "Yes, non-Opec production excluding the US has actually declined for the past two years."

Ministers can consider that at their next meeting in May. Not for discussion, according to the Saudi oil minister Ali Al Naimi: the next secretary general.