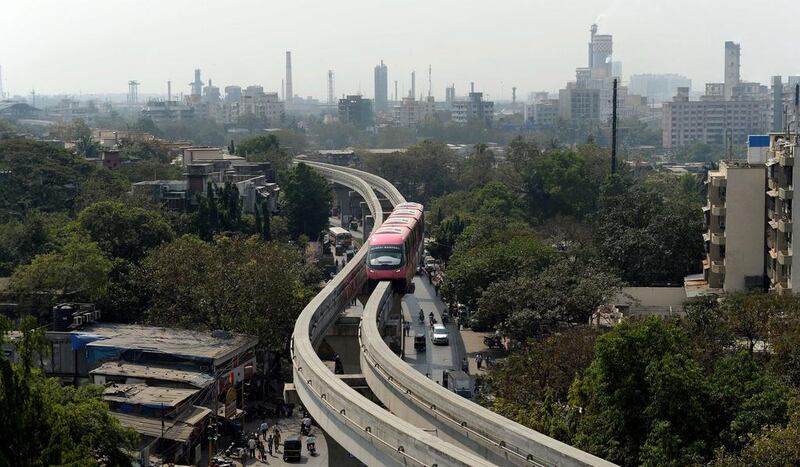

The candy-coloured trains gliding across the skyline of Mumbai are a sharp contrast to the city’s slums, drab buildings, and industrial plants, which passengers overlook.

The 30 billion rupee (Dh1.76bn) Mumbai monorail, inaugurated yesterday and scheduled to open to passengers today, is the first of its kind for India. Its initial phase is being launched after five years and repeated delays to its opening.

The monorail is part of a wider plan to decongest the city’s heavy traffic and overcrowded trains and modernise Mumbai. A metro project is also under development in the city, while a 16.8-kilometre motorway opened up last year. Infrastructure development is considered a vital part of the economic growth of Mumbai and India as a whole, but many projects across the country have stalled or have yet to begin. These bottlenecks are regarded as a hindrance to the country’s economy, which slowed to a decade-low of 5 per cent in the past financial year.

The Mumbai Suburban Railway suffers from severe overcrowding. Its trains carry more than 7.5 million passengers every day. Commuters say that travelling in Mumbai is challenging and stressful, with the norm being that they are crammed on to packed trains or stuck in traffic for several hours each day.

The project is owned by the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) and has been built by a consortium led by the Indian conglomerate Larsen & Toubro and Malaysia’s Scomi Engineering.

The owner’s plan is not to generate profits directly from the monorail, however, but rather it is aiming at wider economic benefits, as travelling in the city becomes easier for commuters.

“No public transport project is profitable,” says Ashwini Bhide, the additional metropolitan commissioner of the MMRDA. “It always need government support. The objective is not to recover the capital cost at the moment. What we want to do is at least recover the operations and maintenance cost. Operations and maintenance should be self-sufficient.”

The fares for the modern, air-conditioned monorail range from 5 rupees to 11 rupees – low by international standards, but higher than Mumbai’s residents are used to paying to travel on the city’s railway.

The monorail project is being introduced in two phases. Initially, it will run from Wadala to Chembur, two areas of Mumbai, covering almost 9km. When the second phase opens up – which is expected next year – the route will cover almost 20km, making it the world’s second longest monorail corridor, according to the MMRDA. The longest is Japan’s Osaka monorail at 23.8km.

Each train can carry up to 570 passengers. Initially, it will operate only every 15 minutes between 7am and 3pm, but the plan is to extend those hours to run between 5am and midnight. Eventually the monorail is expected to be able to carry about 200,000 passengers per day. The trains run at a top speed of 80kph and will travel at an average speed of 65kph

Businesses are hoping that new transport infrastructure will help to boost revenues.

“The monorail project is one of the several projects undertaken by MMRDA to make commuting easier and hassle-free for people in the city,” says Amit Sathe, the head of commercial business at Phoenix Mills, which specialises in developing malls.

Mr Sathe said one of his company’s malls, Phoenix Marketcity, in the suburb of Kurla was expected to benefit from improved access once the monorail reached the area.

Improvements in transport infrastructure typically have a significant effect on property prices and rents in the vicinity, analysts say.

“The anticipated completion of the monorail in the near future and the recent inauguration of the Eastern Freeway will boost demand for rental housing in areas such as Wadala and Chembur,” says Ashutosh Limaye, the head of research and real estate intelligence at Jones Lang LaSalle India. “These projects have direct implications on the commuting time factor.”

Ashvin Gidwani, a media executive, explains that his 12km journey to work in Mumbai can fluctuate widely between 30 and 90 minutes.

“Travelling in Mumbai is always random,” he says. “Your destination time is always uncertain, which really makes doing business very hard. You can never predict traffic, so you just never know.”

The monorail and the metro could be a “blessing” for him once fully operational. But he is concerned that new public transport infrastructure will not be run efficiently or be well maintained.

He asks: “Will they have the same lethargic approach as other public transport operators do in this city?”

Sudhir Badami, an independent transport analyst in Mumbai, is sceptical about the monorail and how effective it can be as a solution to the city’s transport problems. He says that local authorities have focused on costly projects such as the monorail, which has a limited capacity and will not serve the masses.

“The monorail is not the solution for any urban area’s transportation problems,” says Mr Badami. “The capacity is pretty low. It doesn’t really benefit the masses because the cost structure is pretty high – out of the reach of the poor man. It’s one of those things that are marketed to developing countries by the technology developers and it gets sold. It is considered that it is taking you to the world-class city status because you see a nice colourful train going at an elevated level.”

He says that the city would benefit more from a high-capacity, rapid bus system, which he argues would be much cheaper to develop.

business@thenational.ae