In Mazgaon, south Mumbai, where a building collapsed just over a week ago killing 61 people, families residing in dilapidated apartments nearby say they are living in fear for their lives.

Vandana Sonawane lives in a crumbling, decaying apartment block in the area that has been declared unsafe by local authorities.

All the residents have been told to move out of the building. Despite being well aware of the risks, Ms Sonawane, however, along with most of the other residents in the block, have refused to move into a nearby “transit camp” so the building can be demolished.

“We weren’t worried before until the building collapsed at Dockyard Road,” says Ms Sonawane, a 43-year-old housewife, referring to the recent collapse. “I thought my home could last another 100 years, but perhaps it could fall down any day.”

She is one of six family members living in the 180 square foot apartment. Her family has lived there for 80 years.

Residents of the building say that they do not want to move to the temporary accommodation because they feel they could be stuck there for many years.

“We’ve told the BMC [Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation] to give us a proper transit camp and then we’ll move,” says Ranjana Salve, 40. “Otherwise we’ll have to die here or die there. What’s the difference?”

The BMC says it is planning to forcefully evict the residents with help from the police.

There has been a series of deadly building collapses in Mumbai this year that have brought into sharp focus the city’s problems with dangerous and illegal buildings that often house the poor.

Mumbai, with an ever-growing population that is currently more than 20 million, has a severe shortage of land and property prices are sky-high, forcing many residents into unsafe buildings.

There is a lack of good quality affordable housing in Mumbai, leading to unscrupulous developers cashing in on the situation by building poor quality, illegal structures. Corruption is also cited as playing a part in the crisis of lethal buildings.

One collapsed in Mahim, central Mumbai, in June killing 10 people. A four-storey building collapsed in the suburb of Dahisar and another fell down in Thane, during the same month, both causing several injuries and deaths.

In one of India's worst ever incidents, more than 70 people were killed in April when an apartment building collapsed in Thane. The monsoon rains were thought to have weakened already poor quality structures.

More than 950 buildings have been labelled as dilapidated and unsafe by Mumbai’s municipality.

“Many of the older buildings in Mumbai and its surroundings were constructed along inadequate quality parameters and should have been redeveloped long ago,” says Anurag Mathur, the chief executive of projects and development services, Jones Lang LaSalle India.

Even some of the newer buildings in Mumbai are potentially dangerous, he adds. “Apart from using better construction materials and more modern construction techniques, developers need to factor in Mumbai’s climactic conditions, which involve high levels of salinity and dampness. Structural audits need to be performed on older buildings.”

P S Jayakumar is the managing director of Value and Budget Housing Corporation (VBHC), which is building affordable housing developments, including outside the main city of Mumbai. He argues that more needs to be done at a government level to facilitate affordable housing projects.

“The best way to address the challenge is to increase the supply,” Mr Jayakumar says. Bureaucratic delays securing approvals for development of affordable housing are holding back much-needed projects in Mumbai, he says. These processes need to made much easier, he adds. “It’s about letting developers do their job without too much hindrance, too much bureaucracy, paperwork, and delay.”

Across Mumbai, there are instances of people living and working in buildings that are considered to be at risk of falling down.

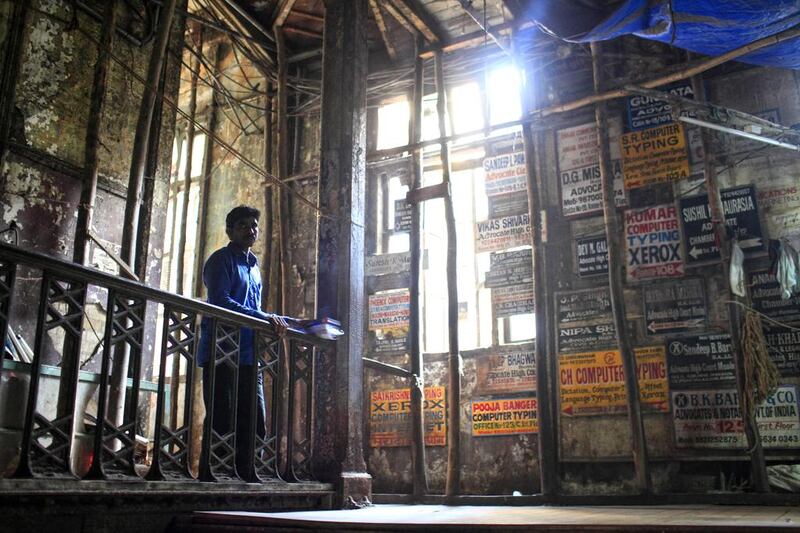

In the heart of south Mumbai, the 150-year old historic Watson’s Hotel, now known as Esplanade Mansion, has a large notice posted at the entrance. It warns passers-by and tenants that the building is “dangerous” and “not fit for human habitation”.

Yet the shabby building, which has electrical wires exposed throughout its dingy interiors and broken structure supported by wooden poles and patched up with pieces of tarpaulin, is busy with lawyers working in their offices. There are also families living there.

One lawyer based in the building, speaking on condition of anonymity, said he thought it was worth the risk of staying there because the rent was so low – 5,000 rupees (Dh298) a month for his tiny office. Archaic laws have prevented owners from raising rents in such buildings, leaving them with limited funds for maintenance and repairs.

“The only place I can afford to be is somewhere like this,” the lawyer says. “It’s close to the courts and it’s affordable. I don’t think the whole thing will fall down soon. It might come down in places. Actually, last year, one portion at the back came down.”

A short drive away, in the Kalbadevi area of Mumbai, Rishi Kumar Pandey, a 23-year-old taxi driver, is found living in a ground-floor apartment of a building on which demolition work has already started. The building has otherwise been vacated and several construction workers are on site, with piles of bricks in the lobby and poles of wood supporting the precarious structures.

Mr Pandey says his uncle owns the apartment and about 10 relatives live in the small apartment with him.

“What should I do? I have no option,” Mr Pandey says. “I have no other place to stay and I can’t afford to go anywhere else.”

business@thenational.ae