Sometimes you just have to know when to quit. Bookshops, like the typewriter and ballpoint pen, belong to a previous era and sooner or later, the last one will close down.

I say this with just a touch of Schadenfreude. You see, I used to own a book store - my first foray into business. It was a labour of love, which is to say I never made much money, but ultimately it did teach me that, sometimes, you just have to let go.

It was the kind of place that once existed in the dingier parts of town. Dusty books crammed onto the shelves. In the corner, a man in a tweed jacket and bad comb-over, muttering to himself by the literary criticism section. Opposite the gardening shelf, two guys who look like they can barely write their own names, exchanging a few bills for a mysterious package.

We would even get a literary celebrity or two. People like Sinclair Beiles, a South African poet who ran with the Beats and was an editor at Olympia Press in the 1960s. It was from Beiles that William Burroughs, the American novelist and poet, obtained the pistol with which he attempted to shoot an apple off his wife's head, putting a bullet between her eyes instead. Ah, those poets.

When the chain-store book marts, with their barista coffee and high-gloss best-sellers began to arrive, I didn't stand a chance. Even dusting the shelves didn't help.

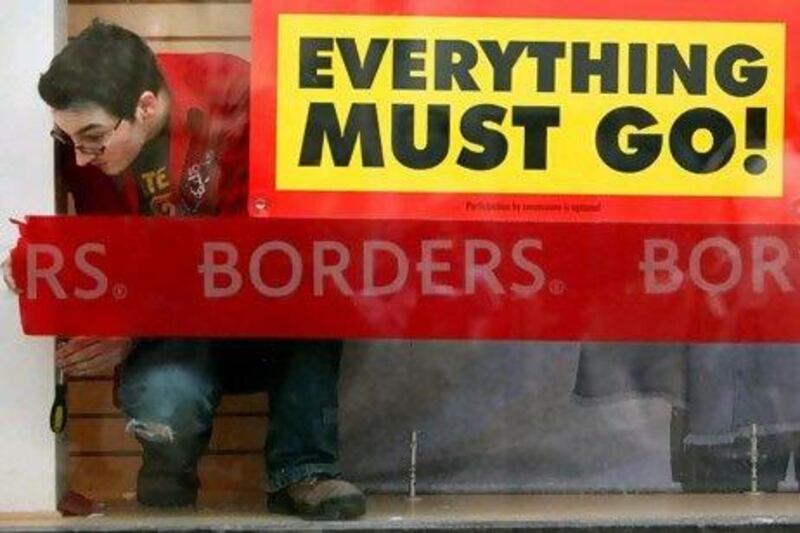

What I learnt the hard way is that some business models simply do not survive the passage of time. First it was the little guys, like me. And now it's the turn of the big boys. Borders UK is no more, and the US wing of the chain is hanging on by its fingernails after filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection a few weeks ago.

Barnes & Noble had to suspend its quarterly dividend - a way of saying there wasn't any money in the kitty for shareholders.

But it's always difficult to give up something in which you have an emotional stake. This is why it is so hard for individuals to manage their own investments. Buying shares or property can be an intensely personal choice. The research it takes means that a decision to buy Apple or GE stock, or the little place in a quiet cul-de-sac becomes, in a sense, a reflection of your smarts.

The failure to quit is a result of our natural aversion to uncertainty. We don't like change, especially when change brings risk with it. Instead, we'd rather keep repeating a formula, even when it becomes apparent to others that there is danger ahead.

I suspect the failure to quit may also explain why the now distant property boom went on for so long. Once individual investors found they could make cash out of their houses, it was hard to stop.

Even the best get it wrong. In 2000, Fortune magazine ran a list called "10 Stocks To Last The Decade". The list was based not only on the values of these counters as they were then, but also "sweeping trends" that it identified would have a significant impact on value in years to come.

Right up there on the list were Enron and Nortel. Of the rest, barely any are worth a mention. The point is not that the gentlemen at Forbes got it wrong; nobody, after all, can read the future, not even Forbes. The real folly would be to hang onto an investment when it becomes clear that initial expectations are not going to be met.

Maybe it's the Buffett factor. Warren Buffett is by far the most successful investor and the world's third-wealthiest man. He has famously made his fortune by choosing good stocks then refusing to sell, in good years and bad.

He has become the benchmark of successful investing and many would like to emulate him. But Mr Buffet is something of an anomaly - an eccentric who began hoarding shares in the 1950s, a very different world from that of today.

He has much to teach about consistency and picking winners. But in the recent credit crisis, he took a hit that ran to more than US$6 billion (Dh22.1bn) at one point. Then again, he can afford it. Small investors, though, need to be ready to dump and run when the moment comes.

Winners never quit, they say. When it comes to your money, it's knowing when to quit that keeps you in the game.

Gavin du Venage is a business writer and entrepreneur based in South Africa.