The British pound isn’t the only global currency that has been crashing lately — the South African rand has taken an even greater hammering amid growing political and economic uncertainty.

But while British expatriates in the UAE have been taking advantage of Brexit uncertainty to send money home at favourable exchange rates, South Africans find themselves in a more complicated situation. Many are reluctant to send money to their home country for fear that the rand's troubles could have much further to run.

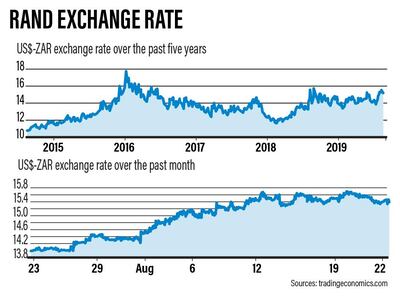

The decline of the rand is a steady, long-term trend but one that has accelerated lately. Fifteen years ago, one US dollar bought 6.54 rand. Five years ago, the dollar had strengthened to 10.70. At time of writing, one dollar buys 15.22, more than double the amount it bought in 2004. That follows a drop of almost 10 per cent in the last month alone.

The recent decline was sparked by several factors, including weak economic growth, employment rates of 29 per cent, the $16 billion bailout of state-owned power monopoly Eskom and rumours of an IMF intervention. South Africa’s economy contracted 3.2 per cent in the first quarter, the most since the 2009 recession.

South African expat David Julies, 48, says the short-term benefits from the rand’s latest devaluation are overshadowed by the longer-term challenges facing his country.

While Britons in the UAE have enjoyed a salary rise in sterling terms, the impact isn’t as strong for South Africans, due to spiralling inflation back home. “Our spending power in South Africa hasn't increased much, so there’s no real impact when sending income back,” says Mr Julies.

The general medical practitioner relocated to the UAE with his wife Maria to work as a hospital administrator in Al Ain and build a stable future for their two children. At the time of his job interview in 2014, the rand was relatively strong, trading at 2.98 to the UAE dirham, but it fell sharply as then-President Jacob Zuma launched a string of controversial cabinet reshuffles. By 2017 the exchange rate had dropped to 4.47, which meant it had lost half its value in three years.

Sentiment picked up after Mr Zuma resigned in February of last year, to be replaced by current President Cyril Ramaphosa, but the rand has now dropped back to 4.15 amid rising economic concerns.

Mr Julies has responded by almost doubling his usual monthly remittance and prepaying short-term South African expenses such as life insurance premiums and school fees, as well as settling a car loan, but says currency weakness remains a double-edged sword.

“I've decided against topping up my South African saving accounts because it is difficult to predict how far the rand may drop in future,” he says.

Mr Julies is not the only UAE expat wary about building long-term savings in South Africa, where it may be subject to currency volatility. Armand Loggenberg, 41, sends money to South Africa to meet family commitments, so he has enjoyed some advantage from recent rand weakness, but says the devaluation rate makes it a bad place to invest for the future.

“When I moved to the UAE two-and-a-half years ago, the UAE dirham bought 3.20 rand, lately it has been trading at around 4.20,” says Mr Loggenberg, who lives in Dubai and is head of aerospace safety for the Dubai Civil Aviation Authority.

If Mr Loggenberg had left his retirement pot in South Africa it would have depreciated by almost a third in that time, and there could be worse to come. He says most South Africans he knows store their long-term wealth elsewhere.

“I might get a little more by sending money back now, but the devaluation rate is so high it makes far more sense to invest offshore,” he says. “Political instability is so high at the moment and I don't want to go back until that changes drastically, and realistically, nothing will change for years.”

Rather than sending money home, Jen Louise, 40, is taking advantage of favourable currency shifts to get her money out of South Africa at a decent exchange rate.

“The minute the British pound dropped I sent the maximum I could for this year from South Africa to the UK,” says Ms Louise, a health care professional who plans to retire either in the UK or Spain. “I can't imagine there are many actually sending money back to South Africa, unless they’re helping to support family.”

Ms Louise says many of her South African friends have similar plans to retire and build up a savings pot elsewhere. “Even South Africans who are not expats sent rand to the UK when the pound dropped recently,” she says. “They were wise to take advantage, as sterling is already back up against the rand.”

The situation was different when Ms Louise moved to the Middle East in 2001, working first in Saudi Arabia followed by a spell in Abu Dhabi. “All my South African friends sent money back home and we used to rejoice when the rand got weak,” she says. “All that money paid for properties, education, mortgages, charities and churches. I knew one girl who sent her entire salary to her local church for a year to help build houses, while I supported the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals charity.”

Those days are now over. “All the South Africans I know either send nothing home, like me, or the minimum to support family, and save everything they can in the UK or another country of choice,” she says.

South African expat Henry Hollingdrake, who works in financial services in Dubai, says it makes sense for his countrymen to store their wealth offshore and hedge against foreign exchange risk by investing in a spread of different asset classes and currency bases, such as euros, Swiss francs, British pounds and US dollars.

“The problem with investing in a volatile currency like the rand is that if your investment in a South African equity increases, say, by 50 per cent but the currency falls 50 per cent and the original trade was executed in, say, US dollars, then effectively you are back at square one. You have lost all you have gained,” he explains.

South African expats in the UAE face a further complication, in the shape of the controversial South African Expat Tax, which comes into force in March next year, when it will tax expats on all income exceeding 1 million rand (Dh241,590). The weak rand aggravates the problem, as expats will see more of their foreign currency earnings falling above that threshold.

Mr Hollingdrake says many South African expats now want to “financially emigrate” but may find that escaping the punitive tax isn’t so easy. "Financial emigration can cost you a lot of money — and you could still end up paying the tax anyway.”

What matters is your residency, rather than domicile or citizenship, he adds. “The problem is that residency is a subjective term and not always measured in terms of actual days away or days in a certain country. If you are a contract worker, it is even harder to prove non-residency,” he says.

Anybody who wants to change their residency status or at least be treated as a non-resident needs to tread carefully, and in some cases may need to prove they have a stronger residency elsewhere.

These are challenging times for South African expats who want to keep ties with their country. “Emerging markets are at the mercy of wider events, they are not always in control of their own destinies,” says Mr Hollingdrake.