The Indian Premier League, the cricket tournament launched three years ago, changed the way the colonial-era sport is viewed in the subcontinent.

India Sport a titan of business

Indian Premier League The UK-based consultancy Brand Finance says the Indian Premier League's brand value dropped by 11 per cent this year to US$3.67 billion (Dh13.48bn). But the brand value of the top franchises, which are owned by leading corporate giants, grew.

Venky's – Blackburn Rovers In November, the Indian poultry company Venky's – a subsidiary of the 50bn rupee (Dh4bn) Venkateshwara Hatcheries – completed the takeover of the English Premier League club Blackburn Rovers for a reported $70m.

IMG Worldwide – Reliance In December, the sports and entertainment company IMG Worldwide, led by the billionaire private equity investor Ted Forstmann, signed a $140m deal with Reliance Industries led by the tycoon Mukesh Ambani to promote professional football in India.

Bharti Airtel – Man United Two years ago, India's largest cellular company Bharti Airtel signed a $15m deal with the English Premier League club Manchester United, which will allow millions of Bharti subscribers to view matches and news clips related to the renowned football team on their phones.

It was no longer a gentlemen's game played in spotless whites on virgin greens. IPL turned cricket into "cricketainment" - a vacuous, showbiz-fuelled sport played in front of baying crowds in packed stadiums and a mammoth television audience.

The US$3.67 billion (Dh13.48bn) sporting extravaganza emerged as the favourite marketing vehicle for hordes of commercial brands.

Above all, the IPL reaffirmed cricket as a money-magnet - luring viewers, sponsors and advertisers in a way that no other sport in India can match.

But the English Premier League football club Liverpool - one of the world's most famous sporting names - is set to challenge the notion that India is a one-sport nation.

The northern English club plans to open a football academy next month on the outskirts of New Delhi - to be headed by and named after the former England midfielder Steve McMahon - in partnership with the Carnoustie Group, a Noida-based sports infrastructure company that owns a polo team and a paragliding academy.

Liverpool did not disclose the size of its investment in the project, which is only the second such venture in Asia. Under the arrangement, 500 students will be trained by professional coaches, including Mr McMahon, who will travel to India for 10 days each month.

Steve Turner, the head of Liverpool's overseas academies, says plans are afoot for similar ventures in Mumbai and Goa next year, part of Liverpool's global strategy to have "a footprint in every continent in the next three years".

He expresses confidence that there is enough appetite for football in India to make the new academies a success.

"A lot of people in India and Asia who are big fans of Liverpool don't get to touch and feel the club's magic," Mr Turner says. The proposed academies "would help them do that".

The consumer research company AC Nielsen found in a survey last year that 47 per cent of India's 1.21 billion people described themselves as football fans.

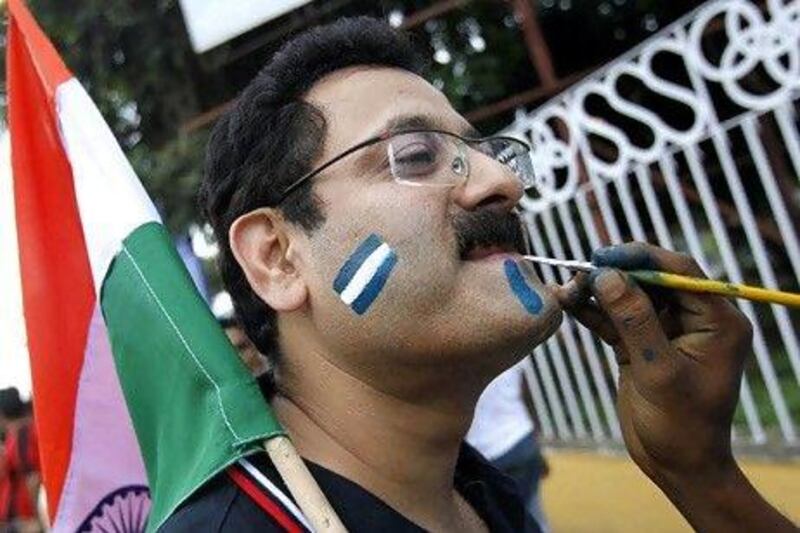

This was reflected in India's first Fifa-sanctioned match - a friendly contest between Argentina and Venezuela - in the eastern city of Kolkata on Friday. It was organised by India's Celebrity Management Group (CMG) in partnership with the All India Football Federation.

CMG says it earned about $4.5 million from broadcasting rights, sponsorship deals and ticket sales of the game - the largest-ever revenue collection from a single game in the country.

India has long been viewed as a sleeping giant that lacks the sort of rapacious hunger for sports promotion that saw neighbouring China transform itself into an Olympic powerhouse.

But the marriage of big business with sports is rapidly changing that perception, observers say.

The success of the IPL, which saw corporate giants such as Mukesh Ambani's Reliance Industries, Vijay Mallya's United Breweries, and Ness Wadia's Bombay Dyeing invest in private teams, revealed the blueprint of a new business model.

Several corporate giants have expressed the desire to invest in the next sports league in India, a nation with a young population avidly looking to branch out to other sports besides the wildly popular cricket.

Last year, the Indian domestic poultry company Venky's bought Blackburn Rovers, another English Premier League club, for a reported $70m, and pays the club's star players to appear in advertisements for its products.

In December, the sports and entertainment company IMG Worldwide, led by the billionaire private equity investor Ted Forstmann, signed a 15-year, $140m deal with Reliance to "radically restructure, overhaul, improve, popularise and promote" professional football in India.

Under the deal, IMG Worldwide and Reliance will control the Indian national football team and all future professional leagues.

The sport "is the second most popular sport in the country, with a massive and passionate fan following," Mr Forstmann said.

"The excitement and exuberance that was evident in the streets of the major cities in India during the Fifa World Cup [held last year in South Africa], as well as the estimated 110 million Indian television viewers of the games, is a good indication of potential for future success."

In 2009, India's largest mobile phone operator, Bharti Airtel, entered into a $15m deal with England's top premiership football club Manchester United, which will allow millions of Bharti's subscribers to view matches and news clips concerning the team on their phones.

In late 2007, Vijay Mallya, chairman of United Breweries and Kingfisher Airlines, bought a 50 per cent stake in the Spyker, a UK-based Formula One racing team, for $120m and rebranded the team as Force India.

Even though investments in sports are growing, a study by the sports infrastructure company TransStadia warned that India's poor infrastructure and labyrinthine bureaucracy were among the biggest hurdles facing potential investors.

But sports infrastructure has improved dramatically, with multi-purpose sports complexes built in recent years, in part for the Commonwealth Games, which India hosted last year, spending $6bn.

However, some observers say that other sports such as football might never achieve the cult status - or the commercial success - that cricket enjoys in India.

The audience rating company TAM Media Research in Mumbai says that cricket dominated television ratings last year, with about 176 million viewers, compared with 57 million in 2003. The sport accounted for 85 per cent of the total TV sports advertising spending.

Last year, 13bn rupees (Dh1.04bn) - out of a television advertising total of 105bn rupees - was spent on cricket, 20 per cent more than the previous year.

ESPN Star Sports, which was the official telecaster of the Cricket World Cup in India this year, is reported to have earned 8bn rupees from it. Indian cricketers are some of the world's highest-paid sportsmen. Each IPL team spends an average of $2.5m to sign a player, only slightly less than the US National Basketball Association teams, which spend an average $2.6m per player.

"In the subcontinent, [cricket] is the equivalent of the [US] National Football League, plus every other major sport rolled into one," says John Kosner, the senior vice president of sports of the sports broadcaster ESPN.