The lights may soon go out for Africa's biggest economy, which is now struggling to catch up after years of underinvestment in energy.

The South African power utility Eskom has warned of impending shortages as it operates at capacity. It expects a shortfall of 3,000 megawatts (MW) this year - enough to run a sizeable city.

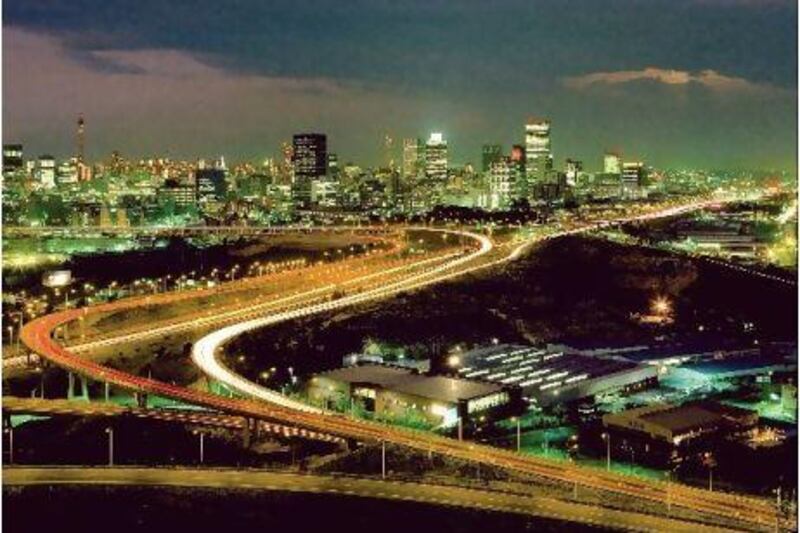

In 2008, the country was brought to a standstill by shortages. Mines stopped operating, factories ground to a halt and trainsstopped. In the glitzy malls of Johannesburg's northern suburbs, shoppers were plunged into darkness and groped their way out through the marbled halls to their BMWs.

This was especially galling in a country that for years courted foreign investors using its cheap power as a selling point. It has also been a source of pride for the ruling African National Congress that the smoky haze that hung over black townships during the apartheid years has now largely disappeared.

Thanks to a breakneck electrification effort, eight out of 10 people now have electricity. Before the end of white rule in the mid-1990s, less than 40 per cent of the population enjoyed power in their homes.

But somehow, the wheels came off. Soon after the millennium, the government began flirting with the privatisation of Eskom. As it tried to figure out how to sell its power stations, it ordered a halt to any further investment in capacity, even though its own experts warned Eskom would reach its generating limit by 2007.

By 2008, "load-shedding", a euphemism for rolling blackouts, brought much of the country to a halt. Within a few months, however, Eskom managed to end blackouts through a combination of bringing old, mothballed stations back on line and a hefty rise in power tariffs. It also revived dormant plans to build new power stations.

As a result, Eskom intends to spend 385 billion rand (Dh201.8bn) up to 2013, and more than 1 trillion rand by 2026, to double capacity to 80,000MW by 2026. It is also licensing private producers to help out. A coal-fired station costing 33bn rand and set to produce 4,800MW is under construction. It is scheduled to enter service in 2015.

The utility will also invest an initial 10bn rand in two projects that include a 100MW wind farm and a 100MW solar thermal plant. Dr Steve Lennon, the managing director for Eskom corporate services, says the company has bigger plans for renewable energy. "At a minimum we would see very close to 2,000MW in solar thermal by 2030, but with a possibility of a lot more, depending on how the business case comes out," he says.

A 5,000MW solar park in the arid north of the country is also being discussed.

Dr Lennon says Eskom foresees its reliance on coal dropping from 95 per cent now to 60-65 per cent by 2030. Solar and wind power together will supply up to 10 per cent of the energy mix, with the remainder being nuclear power.

Some, however, wonder whether the money being diverted to renewable energy could not be better spent elsewhere. "Wind and solar are developing technologies, but thermal coal generation has been around for 150 years," says Professor Philip Lloyd of the Energy Institute at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology.

The passion for renewable energy might make sense for highly developed economies, but for a country such as South Africa, which has pressing social needs, the authorities should focus on cost, not expensive renewables, Prof Lloyd suggests.

It costs about 250 per cent more to produce electricity from wind, the next cheapest option, than coal,he points out. South Africa is one of the world's largest producers of coal. "Nobody would expect Kuwait to give up making the best use of its abundant oil reserves, so why should we give up ours?" he adds.

Prof Lloyd says that Eskom has had to substantially raise tariffs to pay for new generation capacity, to the point where many of the poor simply cannot afford electricity. People are again turning to wood, coal and paraffin for heating and cooking.

The result is a rise in smoke pollution, and he believes the reversion to burning fuels at home may also explain the rise in fires that flare up from time to time in shanty towns, destroying hundreds of homes. Costly renewable-energy projects will only burden the poor further, he says.

In the meantime, Eskom is in a race against time to make up the shortfall in power generation. It has commissioned a coal station and is looking to add to the country's existing nuclear capacity. With South Africa's economy expanding once again, the race is going to be close.

* with Reuters