Lee Iacocca, the charismatic US auto industry executive who gave America the Ford Mustang and was celebrated for saving Chrysler from going out of business, has died at the age of 94, Fiat Chrysler said.

Iacocca died Tuesday at his home in Bel-Air, California of complications from Parkinson’s disease, his daughter Lia Iacocca Assad told the Washington Post.

“The company is saddened by the news of Lee Iacocca’s passing. He played a historic role in steering Chrysler through crisis and making it a true competitive force,” Fiat Chrysler Automobiles said.

“He was one of the great leaders of our company and the auto industry as a whole. He also played a profound and tireless role on the national stage as a business statesman and philanthropist,” the company said.

During a nearly five-decade career in Detroit that began in 1946 at Ford, the proud son of Italian immigrants made the covers of Time, Newsweek and The New York Times Sunday Magazine in stories portraying him as the avatar of the American Auto Age. One of the first celebrity US chief executives, his autobiography made best-seller lists in the mid-1980s.

Iacocca was a cracker-jack salesman. He encouraged his design teams to be bold and they responded with sports cars that appealed to baby boomers in the 1960s, fuel-efficient models when petrol prices soared in the 1970s and the first-ever family-oriented minivan in the 1980s that led its segment in sales for 25 years.

“I don’t know an auto executive that I’ve ever met who has a feel for the American consumer the way he does,” late United Auto Workers Union President Douglas Fraser once said. “He’s the greatest communicator who’s ever come down the pike in the history of the industry.”

Iacocca also had some duds, such as the Ford Pinto, an economy car that became notorious for exploding fuel tanks. “You don’t win ‘em all,” he said of the Pinto.

He won a place in business history when he pulled Chrysler, now part of Fiat Chrysler, from the brink of collapse in 1980, rallying support in US Congress for $1.2 billion (Dh4.4bn) in federally guaranteed loans and persuading suppliers, dealers and union workers to make sacrifices. He cut his salary to $1 a year.

Iacocca was often described as a demanding and volatile boss who sometimes clashed with fellow executives.

“He could get mad as hell at you, and once it was done he let it go. He wouldn’t stay mad,” said Bud Liebler, vice president of communications at Chrysler during the 1980s and 1990s. “He liked to bring an issue to its head, get it resolved. You always knew where you stood with him.”

Iacocca often spoke of his immigrant roots and how America rewards hard work. When he was tapped by President Ronald Reagan in 1982 to be chairman of a campaign to restore the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, he said he accepted the job as a way of honouring his parents.

The campaign raised more than $350 million, more than double the initial $150m goal.

Iacocca began his career just as post-war prosperity kicked the Auto Age into high gear. By the 1970s, many new suburban homes came with a two-car garage.

Lido Anthony “Lee” Iacocca was born in the Pennsylvania steel town of Allentown on October 24, 1924. His father, Nicola, owned a hot-dog stand he called The Orpheum Wiener House - a foretaste of his son’s later marketing creativity.

In high school he was freshman class president, “a big shot”, he had thought. But when he stopped shaking his classmates’ hands, he lost re-election. “It was an important lesson about leadership,” Iacocca wrote.

He was a diligent student, made the debating team and was a star in Latin class. Sophomore year he survived rheumatic fever, an illness that later kept him out of the military during Second World War and graduated 12th in a class of more than 900.

Iacocca enrolled in Lehigh University, earning his engineering degree in fewer than four years and received a fellowship at Princeton for his master’s degree.

After joining Ford, he realised right away he was better at marketing than engineering. Ten years later, when his district had the worst sales in the country, he came up with a marketing campaign, “56 for ‘56” - buyers could get a 1956 Ford with 20 per cent down and three years of monthly installments of $56.

The plan took off like a rocket and Ford executive Robert McNamara, who would become secretary of defence in the Kennedy administration, made it part of Ford’s national sales strategy.

Iacocca's relationship with the Mustang was cemented when both Time and Newsweek featured him and the car on their covers in April 1964. By 2013, about 9 million Mustangs had been sold.

Gene Bordinat, Ford’s design executive at the time, said of Iacocca’s contribution to the Mustang’s popularity: “We conceived the car and he pimped it after it was born.”

It was cheap to produce and generated big profits. For years, it was Iacocca’s signature achievement.

The low moment in Iacocca’s career though came in 1978, when Henry Ford II fired him. He asked why, reminding his boss that the company had earned record profits of $1.8bn two straight years. Ford replied: “Well, sometimes you just don’t like somebody.”

The firing made national news. Iacocca never forgave Ford, and he described his former boss as a spendthrift and dictator.

Iacocca’s exile from Detroit board rooms was brief. Within weeks he accepted the presidency of Chrysler, even though its market share was shrinking and losses were deepening.

In 1979 Chrysler was facing twin blows of spiking interest rates and a second oil shock that doubled the price of petrol. When the US economy plunged into recession, sales at every car maker plummeted.

Iacocca searched for a merger partner but when no takers emerged, he turned to the government for up to $1.5bn in loan guarantees. He pounded on the doors in Washington, assisted by dealers and union officials who knew their brethren would be out of work if Chrysler folded.

Asking for federal help was controversial, and one editorial cartoon depicted a child asking what the US Capitol was called. “The Chrysler Building” came the answer.

Iacocca won the loan guarantees but they required broad sacrifices, of plant closures, pay cuts for factory workers and layoffs of white-collar staff.

He put his personal reputation on the line, and in the end, it was a tour de force of leadership. Factoring in positions at Chrysler, its dealerships and suppliers, he saved more than 500,000 jobs.

“People saw him in the trenches,” Mr Liebler said. “When we needed the loan guarantees and he was pounding the halls of Congress, the dealers were with him ... he worked his head off day and night, and everyone who was involved in any way with Chrysler knew it.”

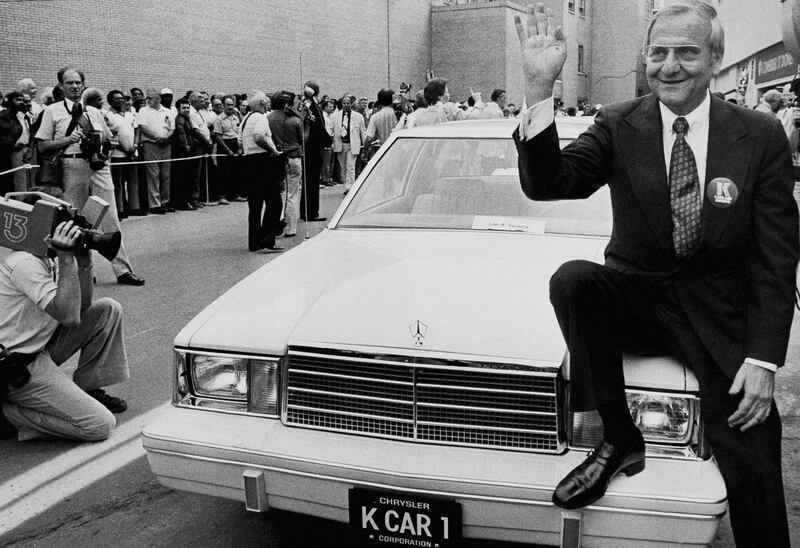

About that time, Chrysler’s introduction of the smaller, fuel-efficient “K Cars” gave it a boost. In a series of no-nonsense television commercials, Iacocca barked, “If you can find a better car, buy it!”

He paid the loans back seven years early, and in 1983, a cartoon showed frantic executives of the troubled US airline industry shouting into a phone, “Get me Lee Iacocca!”

But Iacocca’s star faded in the late 1980s as Chrysler floundered again.

Chrysler struggled through the 1990-1991 economic downturn, losing $800m in 1991. Iacocca refused to cut new product spending, and by 1992, the new Jeep Grand Cherokee and LH saloons led to a $732m profit, while Ford and General Motors were in the red.

With Chrysler profitable again, Iacocca stepped down at the end of 1992. He lived out his latter years in stylish Bel-Air, California.

In retirement, Iacocca invested in the casino business and a line of imported olive oil, and he joined corporate boards.

He penned Where Have All the Leaders Gone?, a 2007 book critical of American leadership, especially President George W Bush.

Iacocca had two daughters with his first wife, Mary, who died of diabetes in 1983, prompting him to start a family foundation to fight the disease.

After Mary’s death he married twice more. His second was brief and ended in annulment, while his third ended in divorce.