Not sure how many people play word association in this part of the world, but say "Turkey" to a Lebanese and the reply might be "visa", simply because we no longer need to apply for one to visit the Eurasian country (and this is a big deal for a people whose applications are normally scrutinised like a Cat scan wherever they want to travel).

Or the answer might be "Ottoman" - or the Arabic Othmanieh. The Turks, or rather the Ottomans, did after all rule our ancestors for 400 years, but those up on their more current - excuse the pun; you'll see why in a second - affairs might say "electricity".

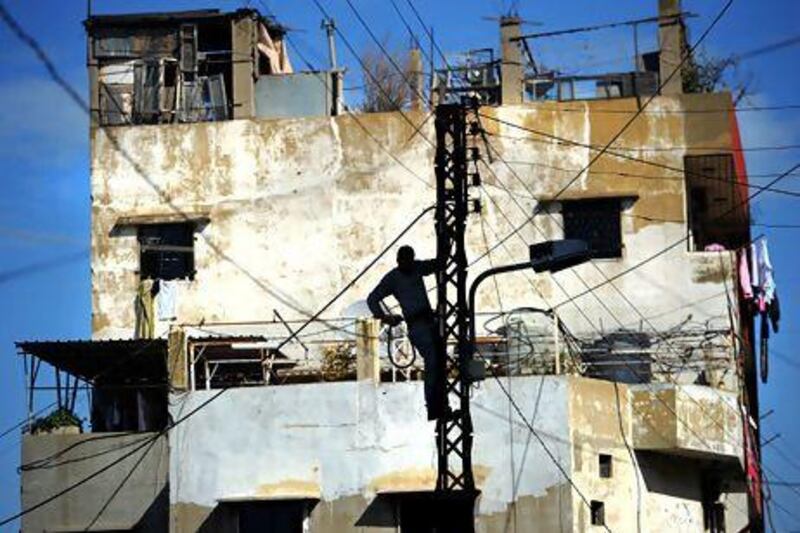

This is because it was the Turks who earlier this year agreed to eventually supply the two power-generating ships that our government has assured us will ease the chronic and shameful power shortage that has kept the Lebanese in misery, and made the country an investment backwater for more than three decades. I say eventually, because this week, the energy minister Gebran Bassil, who is also the son-in-law of Michel Aoun, the leader of the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), admitted the ships had yet to dock in Beirut because there had been a problem with payment.

In the meantime, winter approaches and Lebanon's national grid continues to run at only 65 per cent capacity. The joke is that the boats, if and when they arrive, were never meant to make up this shortfall, but to simply maintain the current - oops, there we go again - levels of supply as various power plants undergo routine service.

The government, especially its ministries run by FPM, has been involved in a prolonged game of smoke and mirrors in the claim to be addressing Lebanon's infrastructure failings.

The FPM may have sold itself as the party of technocrats, but the suave young men, who try to convince us they are rolling up their sleeves to fix the country, have not delivered.

The telecoms tsar, Nicolas Sehnaoui, has done little to bring down the cost to the customer of the two state-owned but exorbitantly priced and inefficient mobile networks, nor has he delivered fast enough internet to help drive local business, let alone make Lebanon a viable investment destination.

Mr Bassil, even if we throw in the by now famous Turkish deal, has failed to make any concrete advances on the electricity crisis, while his handling of tenders for surveying and eventually extracting Lebanon's oil and natural gas has also been shrouded in opacity.

But it's not just this government's spectacular incompetence. There is a sense of deep-seated resignation that nothing will change in a country with a deep-rooted sense of political and private self-interest, compounded by a hefty dollop of sectarian suspicion.

This week the International Finance Corporation and PricewaterhouseCoopers revealed that the Middle East countries have the least demanding tax systems in the world.

OK, the oil-rich GCC nations have contributed to the low ranking, but in Lebanon, where the basic rate of income tax is 7 per cent, tax avoidance is something of a badge of honour and a sign of being smart. It is a far cry from Europe or the United States, where it is considered almost as bad as being labelled a sex offender.

Sadly, Lebanon will never move forward as long as there is no accountability, when people are happy to avoid paying tax because there is zero confidence in the state's ability to spend it wisely and where everyone is much happier looking after themselves.

Ironically, the root of this problem may lie in the former Ottoman empire, where it was common for the Lebanese to throw out what garbage they had on to the street just to annoy their imperial masters.

Walk around Beirut today and you will often see surly shopkeepers kick any rubbish lying in front of their business off the pavement and on to the road. It's the state's problem now. Nothing to do with me.

Michael Karam is a Beirut-based freelance writer