Summer is over and Lebanon is licking its wounds.

The season, or mawsam, was a washout. Ramadan falling at the beginning of August did not help matters, but the troubles in Syria surely contributed to one of the worst summers in recent years in terms of revenue for the tourism, retail and hospitality industry.

The outlook is equally bleak.

We have a government that is making a decent fist of being seen to do the right thing without actually doing anything and a global economy that is on the slide. Meanwhile, the Syrian revolution is looking more like the Syrian war of attrition and will continue to affect confidence in the region.

Which is why I was surprised to read the other day that while Standard Chartered Bank had revised down its projected growth rate for Lebanon this year to about 1.5 per cent, it nonetheless maintained a 5 per cent growth rate projection for next year.

"You're right. It's a bit upbeat," said a banker friend. "Maybe they are counting on the Libya effect."

The Libya effect goes something like this: when the last vestige of Muammar Qaddafi's regime is snuffed out, the world is expecting a whole slew of contracts to be tendered by a new regime desperate to get the new country, whatever it's called by then, back on its feet.

Lebanese businessmen, as is their centuries-old wont, will be the first to set out their stalls. They win the contracts and Lebanon's remittance inflow will be significantly boosted. That is the idea anyway.

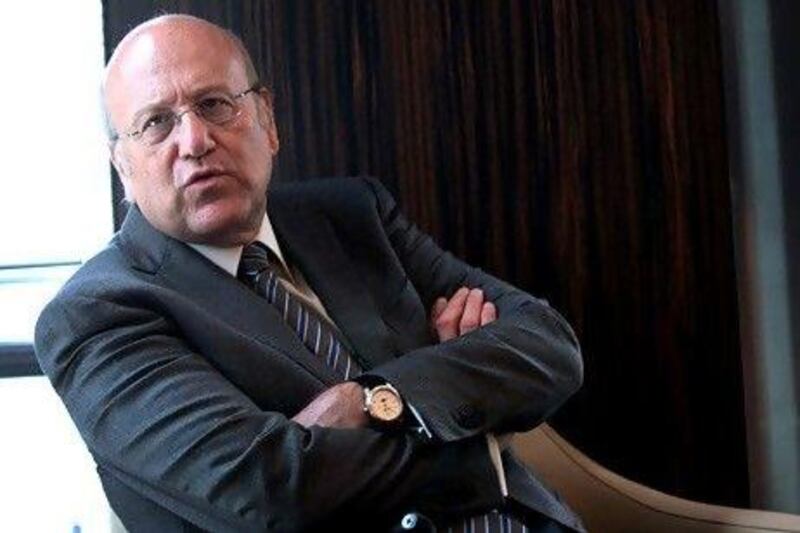

But elsewhere in Lebanon it is mayhem. As I write, the prime minister Najib Mikati is heading to New York where he will face tricky questions from the UN Security Council over his government's inability to reach a decision on the funding of the Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL), the court established to find the killers of the former prime minister Rafik Hariri and at least 30 other victims of political violence since 2005.

Lebanon's share, 49 per cent of the running costs, is a shade over US$30 million (Dh110m), less than 1 per cent of Lebanon's GDP. Given its implications on the future of the country, not to mention the region, it is small change.

But here is the rub. That is assuming we actually want the rule of law, and all that international justice brings with it, to touch Lebanon, to imbue it with a sense of fair play and send a message to killers that blowing up prime ministers, their entourage and a dozen innocent civilians is not how we get things done in the modern age.

Mr Mikati's government, in which Hizbollah has much clout, is uncertain about which way to go on the tribunal. Mr Mikati is, like the late Hariri, a Sunni with a sizeable constituency to appease. Indeed in 2006, when talking to US diplomats, he called Hizbollah a "tumour".

The billionaire former mobile telecoms mogul is by and large an international community kind of guy, but he also has to, if not kowtow to Hizbollah, at least remember that four of its members have been indicted for the killing and the party, not to mention Lebanon's Shia community is not happy.

For its part, Hizbollah or the Party of God, maintains the STL is a Zionist construct and would love nothing more than to see it dead in the water. Hence the government supports the court but is reluctant to stump up the funding.

If we don't pay, nothing concrete will happen in terms of sanctions. (As one Beirut reporter told me this week "if Russia and China will not censure Syria for killing its own people, they are hardly going to go after Lebanon for an unpaid bill" … but then again one never knows.)

It would, however, sour relations with Europe and America, especially those in the US Congress who are already gunning to cut aid to the Lebanese army and the Internal Security Forces.

In short Lebanon will once again look scruffy and dangerous and even less of an interesting option for foreign investment.

So what else do we have to look forward to?

Perhaps the soothsayers at Standard Chartered were looking to Lebanon's relations with Syria in a post-Bashar Al Assad world. The until-now fractured opposition is looking more cohesive, but should the Syrian leader's regime fall, the extent of the fallout in Lebanon, especially how Hizbollah will react, is hard to gauge.

Meanwhile, tourism, as I mentioned earlier, was devastated this year, down 40 per cent on last year, inflation is rising and sales of European cars are down by half with most of the population turning to cheaper South Korean models.

It is a far cry from the pre-civil war days when the Lebanese pound was so strong that taxi drivers could walk into the local Mercedes-Benz dealer and buy a brand new car.

At least we can look forward to faster internet (we have the slowest upload and download speeds in the world) that we have been promised on October 1. Let's see, shall we?

Michael Karam is a freelance writer and communication consultant based in Beirut