When a business becomes untethered from society, serving no purpose but the pursuit of profit, it is time for that organisation to go back to the drawing board. In recent years, we have witnessed dozens of local, regional and international cases of high-profile organisations that gave very little back but took plenty from the communities in which they operated. The banking sector is awash with such stories, as is evident from some regional family businesses.

The tune to which these companies marched uniformly was set to one rhythm - the pursuit of shareholder returns. It was a common calling and an overriding factor in all decision making. All other measures, related to employees, customers and society, barely registered on the scoreboard. This composition played out, reaching its crescendo in the1980s and 1990s, as well as in the first decade of the new century. In fairness to managers who pioneered the focus on shareholder value, prior to this there had been widespread inefficiencies within organisations as they became multilayered bureaucracies. The result was that shareholders were not seeing the returns they had expected or were promised. Yet the pendulum, as it often does, swung too far in the other direction.

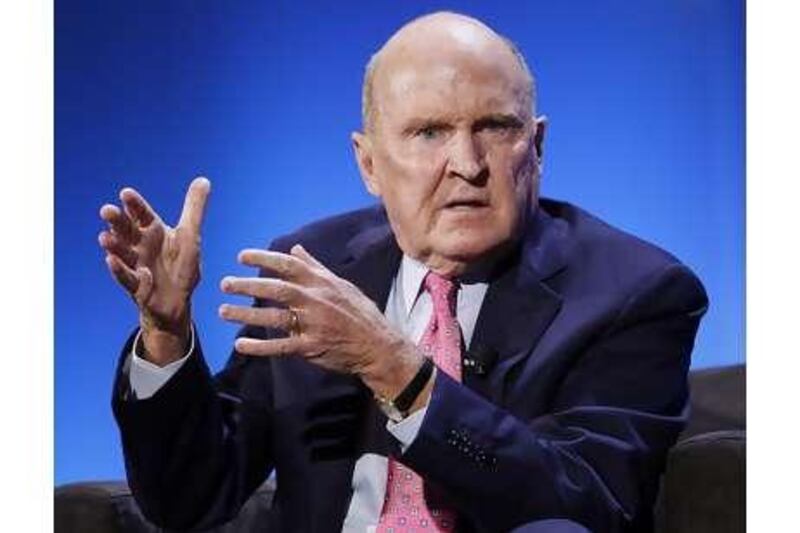

So having experienced both extremes - a neglect of shareholders and the worship of shareholders - it is time to address the imbalance, to reset the clock. In effect, it is time to unlearn shareholder value. If you think this type of talk will not make the grade in the boardroom, you need only to listen to what the arch apostle of shareholder value from the1990s has to say on the subject today. In an interview with the Financial Times in March last year, Jack Welch, a former chief executive of General Electric, said: "On the face of it, shareholder value is the dumbest idea in the world." Since Mr Welch has a formidable global following among managers, his words should carry weight.

So if executives also need to focus on something else, what should that be? Sir Andrew Likierman, the dean of the London Business School, says morality and ethics need to be in the mix. "Ethics and corporate social responsibility in general is not a passing fad; it is a long-term issue. I was teaching business ethics at the London Business School in 1986. It has always been an important component of faculty teaching and is now an integral part of the MBA."

Perhaps we could also add some universal human values? This is advocated by John Mackey, the co-founder and chief executive of Whole Foods Market, based in Austin, Texas. He has been a pioneer in the growth of organic food in the US for the past 30 years. Whole Foods Market today is a Fortune 500 company. Mr Mackey says: "Many of our corporations primarily exist to maximise the compensation of their executives, and secondarily shareholder value, rather than value creation for customers, employees and other major stakeholders.

"The single most important requirement for the creation of higher levels of trust for any organisation is to discover or rediscover the higher purpose of the organisation. Why does the organisation exist? What is it trying to accomplish? What core values will inspire the organisation and create greater trust from all of its stakeholders? The highest ideals that humans aspire to should be the same ideals that our organisations also have as their highest purposes."

Among the timeless universal human ideals he cites are goodness, truth, beauty and heroism, which he encourages leaders to place at the centre of their business model. In so doing, business leaders will unify their organisations and inspire trust from all the major stakeholders - customers, staff, investors, suppliers and the communities in which they exist. He has a point. Whenever we do something that we really enjoy and value, we make a greater effort. Employees in an organisational setting will do the same.

But where to start? How can collective global business language emerge when managers are robotically programmed to obey the mantra of shareholder value? Despite the upheavals of the past two years, it is still firmly entrenched in the management psyche of today, to the detriment of other stakeholders. One initiative launched by Professor Gary Hamel, the author of many popular management books including Leading the Revolutionand Competing for the Future, is the setting up this year of the Management Innovation eXchange (MIX).

The MIX is an open innovation project aimed at reinventing management for the 21st century. Prof Hamel and his co-collaborators at the MIX regard management as a tool and technology for human accomplishment; it is about getting people to do things while not losing sight of all stakeholders. On the MIX you can find a series of management "moonshots". These are a list of make-or-break challenges for managers everywhere. The moonshots are framed as a response to the question: what needs to be done to create organisations that are fit for the future?

There are 25 moonshots, with titles such as "Embed the ethos of community and citizenship", "Increase trust, reduce fear", "Stretch management time frames and perspectives". The MIX is awarding prizes for the best ideas within three moonshots initially, with others to follow. Putting our heads together to create organisations that are fit for the future is the management equivalent of the human genome project or the one-laptop-per-child initiative.

Rehan Khan is a business consultant and writer based in Dubai business@thenational.ae