Customers who are eager to be Sharia compliant are flocking to Islamic banks. Yet as Islamic lending boasts that it charges no interest, crunching the numbers churns out something of a surprise. Some Islamic mortgages charge more than already high interest-based traditional mortgages. You could even argue that an Islamic mortgage is, in some cases, so expensive it is akin to usury. And the terms are often less favourable.

Take the current murabaha rates in Syria and Lebanon. Murabaha is an Islamic equivalent to a mortgage or car loan. Instead of lending the customer money and charging interest, the bank purchases the asset and resells it for a profit to the customer. This profit is the murabaha rate. The going murabaha rate in Syria starts at 5.5 per cent annually, and can go higher than 7 per cent. When you convert these figures to an interest-based mortgage, you get 9.5 per cent and 11.7 per cent respectively. This means that the most competitive murabaha rate is equivalent to the average traditional mortgage rate of 9.5 per cent.

If you purchase a million-dollar home with an annual murabaha rate of 5.5 per cent with 20 per cent down payment and a 10-year term, you end up paying US$440,000 (Dh1.6 million) in "profits" over the life of the murabaha to the bank. If you finance your home with a 9.5 per cent interest-based traditional mortgage with the same terms, you end up paying about $442,000 in total interest to the bank. And the terms on Murabaha are often stricter than those that come with a traditional mortgage. Murabaha products are usually for 10 years, compared with the 20-year or more traditional mortgage. Murabaha also requires a higher down payment.

Unlike, say, in the UK, there are no regulatory laws in Syria that require Islamic banks to quote their product in a way that is equivalent to an interest-based traditional mortgage to allow comparison shopping. The only way the average customer can convert murabaha to interest-based is with the help of a financial calculator and a professional. Given this lack of transparency, are customers unknowingly paying a premium to be Sharia compliant?

"Yes, I think people are willing to pay a premium to be with an Islamic bank," says Mamoun Darkazally, the chief executive of Al Baraka Bank in Syria. "We have a very strong Sharia committee." His bank offers an annual murahaba rate of 5.5 per cent "plus or minus two or three points depending on the client". He says the bank has already financed 150 assets worth 170m Syrian pounds (Dh13.5m) since it opened for business in June.

The other two Islamic banks now operating in Syria also boast high demand for their murabaha products. According to their annual reports, Syria International Islamic Bank doubled its income of murabaha products last year compared with 2008, cashing in 1.4 billion Syrian pounds. Speaking on condition of anonymity, one banker at the Islamic Cham Bank said that in spite of its higher annual murabaha rate of 7 per cent, it has had "so much demand the treasury is now full to capacity with assets".

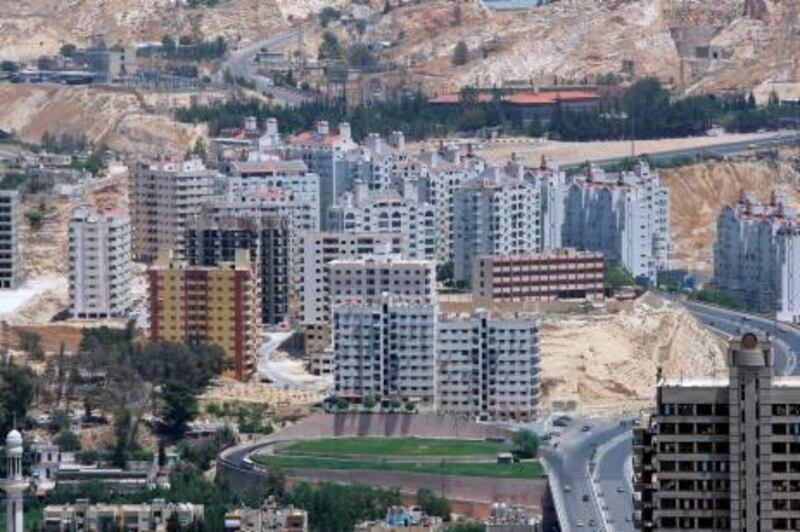

There is another edge to the high lending rates in Syria and Lebanon, which might also explain the increase in demand. Property prices have tripled and quadrupled over the past decade. Beirut has four out of the six most expensive retail locations in the Middle East and Africa, according to this year's report by Cushman & Wakefield, a global property firm based in New York. Damascus Cham Centre, a shopping complex, comes in at seventh place, making it more expensive than Dubai's Mall of the Emirates.

Some bankers are pleased with this, pricing their products on the speculative idea that property prices will continue to rise. Explaining why the traditional mortgage rates are so high, one banker says: "Well, real estate in Syria keeps going up. So even with a high interest rate, the appreciation will still be higher." Mr Darkazally echoes this sentiment. "Real estate prices in Syria will never go down," he says.

Like most Arab consumers, Syrians are averse to borrowing money, which perhaps spared the country repercussions from the global credit crunch. Before 2005, when private banks were first allowed to operate, it was not unusual for the merchants of Damascus to keep their money under their mattress, let alone march into a bank asking for a loan or a murabaha. And Syrians are not flush with cash. The average monthly salary is about $150, and the most a highly skilled young professional can hope for is about $1,000 a month. Wages have barely kept up with inflation, which was 8 per cent last year, according to official statistics.

But Syrians are house-rich. Up to 95 per cent of homeowners own their home free and clear, says Mr Darkazally, having paid for it in cash or inherited it from family. So far no one seems to be borrowing against their home equity, and banks do not yet offer this option. Customers taking out traditional mortgages and murabaha seem to fall into three categories: those who cannot afford to purchase a home in full with cash, businesses that expect enough cash flow to cover the high murabaha or interest payments, and speculators with multiple homes.

So does this constitute aggressive lending? And could the speculative behaviour by customers and bankers on a property boom that has not yet gone bust lead down the same road that brought the world to its knees in the recent credit crunch? "Not in our day," says Mr Darkazally. business@thenational.ae