On the eve of the First World War, Britain's foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey mused that the "lamps were going out all over Europe", adding that "we shall not see them lit again in our time". Many ordinary Iraqis will feel his observation applies to them, too.

Since the official end of the second Iraq war in 2003, life for the people residing in the cradle of civilisation, the lands bounded by the rivers Euphrates and Tigris, has been a throwback to bygone times.

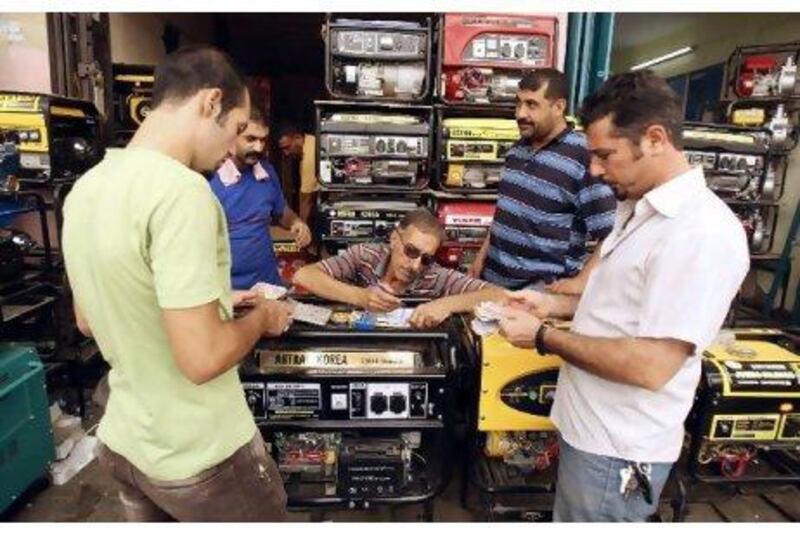

With electricity supply vastly overstretched, Iraqis have had to endure power outages for years. In a country that can draw on some of the world's biggest oil reserves, and that only a few decades back was regarded as the most advanced in the Gulf, this is hard to swallow, and the population took to the streets this year in protest at this failure to supply basic needs.

The causes behind the power shortage are twofold: an insufficient amount of plants needed to produce electricity, and a lack of available feedstock for these plants.

The government has not been oblivious to the problem, and in 2008 bought large-scale power-generation turbines from Germany's Siemens and America's General Electric worth up to US$8 billion (Dh29.38bn). In the same year, Iraq turned its attention to its vast reserves of natural gas, entering negotiations with Royal Dutch Shell over a scheme to process the gas from three major oil developments in southern Iraq - the Rumaila, West Qurna-1 and Zubair fields.

Critics have been vocal. Politicians and bureaucrats fear the deal will give Shell access to gas from future oilfield developments in the south, and say the deal was never subject to a competitive tender.

Pricing has also been a sticking point, and a source of confusion.

The project would initially process 700 million cubic feet of gas a day (cfd), which could rise to as much as 2 billion cfd as oil production rises. There are conflicting estimates on how much the government will be paying the Anglo Dutch company for its gas.

Some reports suggest Basrah Gas Company (BGC), a joint venture between Shell, the Iraqi state and Japan's Mitsubishi, will receive about $5.70 per million British thermal units (mbtu) of gas, while other calculations estimate $2 per mbtu.

A price above the current market rate of about $4mbtu seems unlikely. If the price turns out to be at the lower end of the reported range, the government would still be making a loss as it sells gas to domestic users at $1.04mbtu. To compensate the government for the losses on domestic gas sales, the project could also produce 3,000 tonnes a day of liquefied petroleum gas for export.

To offset investment costs of about $17bn, the contract stipulates the construction of a liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal for export by the end of the decade. This has also attracted criticism, with fears the terminal will strip Iraq of gas needed for domestic use. Proponents of the project point out that the domestic gas market and the LNG market are complementary, as Iraq uses most electricity in the hot summer months, while the international gas market peaks in winter months.

They also counter the critics by pointing to the expertise that Europe's largest company brings with it, and the need to make the deal appealing to the oil major.

"Shell is a renowned company that came up with the solution to a very important problem," says Leila Benali, the Middle East and Africa director at IHS Cambridge Energy Research Associates.

"Iraq has a company come to the table that already has a strong profile in the region.

They need something to recoup their investment, hence the proposal to sell part of the gas internationally. That is the counter argument." Despite vigorous opposition from within the government, many observers expect the deal to get cabinet approval, as the need to make use of the gas as feedstock for power generation is simply too great.

If the government is serious about switching the lights back on, and fuelling the country's industrialisation drive, gas from the southern fields is indispensable.

"Iraq is desperate for power, there is a very ambitious power generation programme that is waiting for approval and feedstock confirmation, so the capture of the gas will be a very welcome development for that programme, says Hakim Darbouche, a research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. "But not just power generation, there is also the issue of industrial reconstruction."

Demand for electricity in Iraq averaged 11,484 megawatts in the second quarter of this year,compared with an average of only 6,574MW of supply. Over the past two years, supply has increased only 6 per cent. It is estimated that demand could rise as high as 21,000MW by 2015.

To counter this surge in demand, Iraq's electricity masterplan calls for the investment of almost $77bn in power-generation infrastructure over the next 20 years.

Apart from failing to push ahead with the construction of power plants, the shortage of feedstock has become a national embarrassment. In spite of the abundance of natural gas, the government in June signed a $365 million deal with Iran for a cross-border pipeline that will deliver 25 million cubic metres of gas per day over the next five years.

But deals with Iran do not sit well with the Iraqi government.