When the company Gary Bell worked for in Dubai faltered last year, he came face to face with the legal system's endemic uncertainties.

Recovering lost wages was a drawn-out battle and it was not immediately clear whether he and his colleagues could force the company to pay back suppliers and employees through bankruptcy proceedings.

"The bankruptcy laws need to be reviewed and the existing ones enforced," he said. "Directors, staff, suppliers, consultants should be aware that if they get into financial difficulty … the laws will not be used to protect them no matter whether they owe or are owed monies. This is the reality of Dubai."

Today, regulators and government officials are still trying to change that reality. The aim is twofold: to create a more equitable playing field for businesses; and to speed up the cycle of failure and success.

The logic is that if businesses can start up and shut down without hindrance - and are backed by the assurance of protection under the law - more entrepreneurs will be willing to give their ideas a try. That, in turn, would speed up a revitalisation following the financial crisis.

"You will see many more steps in that direction because the financial crisis has shown that we are much more intertwined with the global economy, and that also means we need modern laws to cater to the different requirements of being intertwined with this global economy," said Abdul Aziz al Yaqout, the regional managing director for DLA Piper, a global law firm. "That's why you'll see a lot more regulation coming out."

Change in the UAE's insolvency regime is already brewing. In May, Sheikh Ahmed bin Saeed Al Maktoum, the chairman of Dubai's Supreme Fiscal Committee and of Emirates Airline, said updating bankruptcy laws was "a policy priority" and added that "a clear framework for the financial restructuring and reorganisation of companies, based on international principles, is being put in place".

Two months later, Hamad Buamim, the director general of the Dubai Chamber of Commerce and Industry, said insolvency reform was "at the top of the agenda" as part of the emirate's bid to maintain its competitive edge in the region by helping local businesses weather the economic storm.

"Insolvency in many parts of the world is not only about closing a business," he said. "It's also about restructuring a business when it's in such challenging times. It is definitely outdated. It is available but outdated and needs to be reviewed." The UAE has had insolvency laws on the books since at least 1992, when an update to the commercial code included a procedure for winding down companies through the courts.

The law also covered reorganisations, protecting businesses from their creditors and giving them time to get back on their feet. That part of the code is "similar in purpose" to Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the US, which gives companies a chance to restructure instead of just shutting down, according to a recent summary by the Dubai law firm Ali Al Aidarous International Legal Practice.

Yet, while their basic form may be close to western standards, lawyers say, UAE rules are different in that there are many circumstances where businessmen can face criminal penalties. Company directors are treated harshly if they fail to act quickly when a firm teeters on the brink. Companies must declare bankruptcy within a month of missing even a single payment on debts.

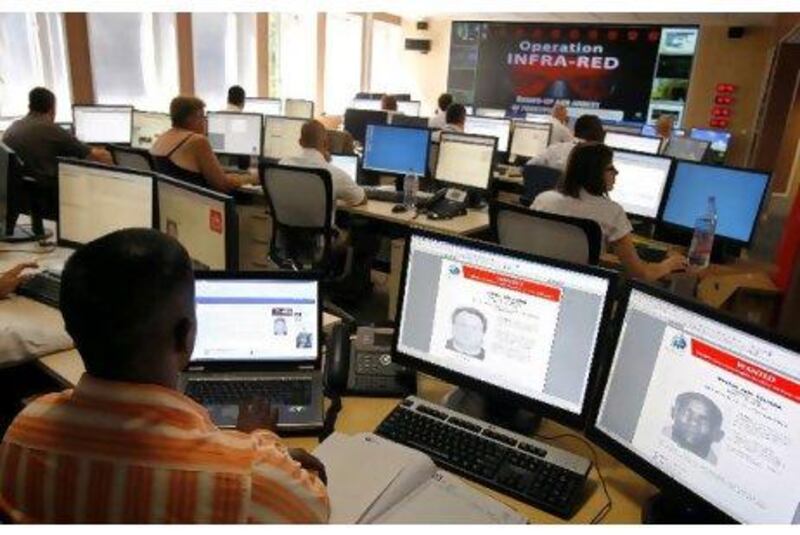

Another drawback is the criminal treatment of bounced cheques. Authorities have detained dozens of executives at airports and put them in jail following the financial crisis because cheques they wrote on behalf of their companies bounced.

"From a legal perspective, we simply cannot continue detaining businessmen at airport points for settling debts," Habib al Mulla, a prominent Emirati lawyer, said last week.

A main issue for proponents of reform is to draw clearer distinctions between financial fraud and run-of-the-mill business failures. Those efforts have been given a boost recently by a new set of courts created last year to tackle bounced-cheque cases involving property transactions in Dubai. Another major advance was the passage last year of Decree 57 in Dubai, which set up a special tribunal in the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) to handle claims relating to Dubai World and its subsidiaries.

The court is functioning as a kind of ad hoc bankruptcy court for the government-owned company, which recently came to an agreement with creditors to restructure US$24.9 billion (Dh91.45bn) of debt. The tribunal, which has procedures based on English law, could influence the development of insolvency regulation outside the DIFC, a specialised financial free zone.

Whatever its shape and scope, few observers dispute the necessity of major reform.