How much inequality is acceptable? Judging by standards before the global economic crisis, a great deal of it, especially in the United States and the United Kingdom.

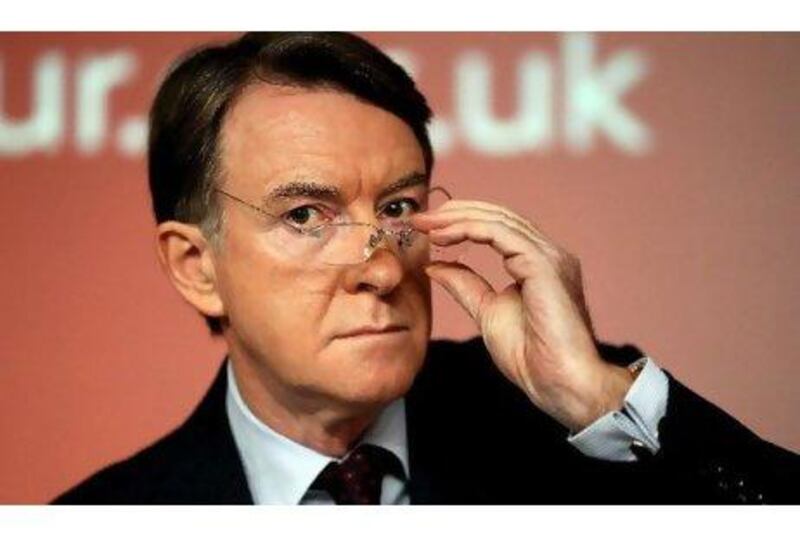

The British Labour peer Lord Mandelson once voiced the spirit of the past 30 years when he remarked he felt intensely "relaxed" about people getting "filthy" rich. Getting rich was what Labour's "new economy" was all about. And the newly rich kept more of what they got, as taxes were cut to encourage them to get still richer, and efforts to divide up the pie more fairly were abandoned.

The results were predictable. In 1970, the pre-tax pay of a top American chief executive was about 30 times higher than that of the average worker; today it is 263 times higher. In the UK the equivalent figures are 47 and 81 times more.

Since the late 1970s, the post-tax income of the richest fifth has increased five times as fast as the poorest fifth in the US and four times as fast in the UK.

Even more important has been the growing gap between average (mean) and median income: that is, the proportion of the population living on half or less of the average income in the US and Britain has been growing.

Although some countries have resisted the trend, inequality has been rising for several decades across the world. The growth of inequality leaves ideological defenders of capitalism unfazed. The poor, it is claimed, are still better off than they would have been had the gap been artificially narrowed by trade unions or governments.

The only secure way to get "trickle-down" wealth to trickle faster is by cutting marginal tax rates still further or, alternatively, by improving the "human capital" of the poor, so they become worth more to their employers. This is a method of economic reasoning calculated to appeal to those at the top of the income pyramid.

After all, there is no way whatsoever to calculate the marginal products of different individuals in cooperative productive activities. Top pay rates are simply fixed by comparing them to other top pay rates in similar jobs.

In the past, pay differentials were settled by reference to what seemed fair and reasonable. The greater the knowledge, skill and responsibility attached to a job, the higher the reward for doing it. But this occurred within bounds.

Top business salaries were rarely more than 20 or 30 times higher than average wages. Thus, the income of doctors and lawyers used to be about five times higher than that of manual workers, not 10 times or more, as they are today.

It is the breakdown of non-economistic, commonsense ways of valuing human activities that has led to today's spurious methods of calculating pay.

There is a strange, although little-noticed, consequence of the failure to distinguish value from price: the only way offered to most people to boost their incomes is through economic growth. In poor countries, this is reasonable; there is not enough wealth to spread round.

But in developed countries concentration on growth is an extraordinarily inefficient way to increase general prosperity because it means an economy must grow by, say, 3 per cent to raise the earnings of the majority by, say, 1 per cent.

Nor is it by any means certain the human capital of the majority can be increased faster than that of the minority, who capture all of the educational advantages flowing from superior wealth, family conditions and connections. Redistribution in these circumstances is a more secure way to achieve a broad base of consumption, which is itself a guarantee of economic stability.

The attitude of indifference to income distribution is a recipe for economic growth without end, with the rich, very rich and super-rich drawing ever further ahead of the rest.

This must be wrong for moral and practical reasons. In moral terms it puts the prospect of the good life perpetually beyond reach for most people. In practical terms, it will destroy the social cohesion on which democracy ultimately rests.

Robert Skidelsky, a member of the British House of Lords, is professor emeritus of political economy at Warwick University

* Project Syndicate