There is a wonderful cartoon in an old issue of The New Yorker of two cigar-chomping banker-types, sitting in high-backed, club-room armchairs, watching as the markets plummet. One remarks casually, "I've got all my money in hand baskets".

I was reminded of it because Lebanon is going to economic meltdown in a very big hand basket.

The country is entering its fifth calendar month without a government and the prime minister-designate Nagib Mikati does not look like forming one any time soon. The problem is that the March 8 alliance, which toppled the government of Saad Hariri in a bloodless coup on January 12 and whose only common denominator is an allegiance to Syria, has been caught off guard by what has become known as the Arab Spring.

The idea was that Damascus was expected to give the new government its blessing but the Syrians have more pressing concerns and a power vacuum in Lebanon may just suit the Syrian government's current needs as it peddles itself as the only regime that can keep the region from imploding.

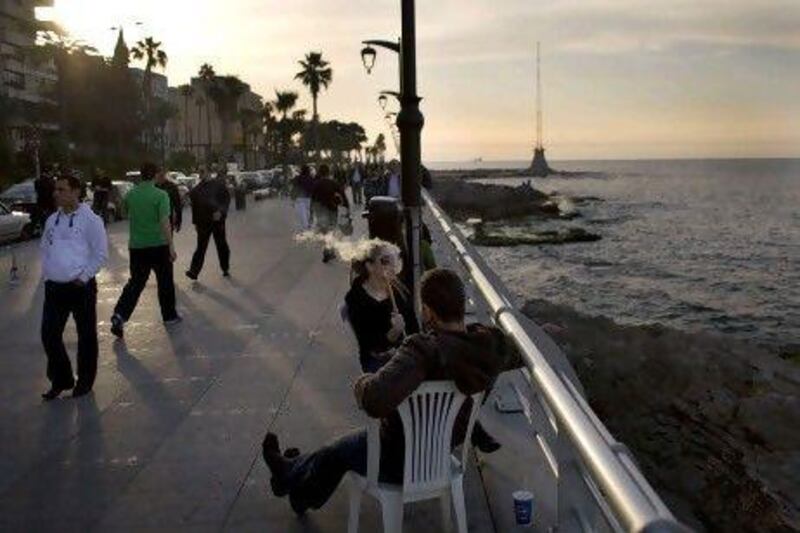

Be that as it may, business in Beirut is hurting. A property developer admitted to me in London last month that sales of luxury apartments in his development along Beirut's famous Corniche seafront were "slow". It was a rare admission as Beirut businessmen are by and large an upbeat herd. But the country has fallen into decline and something had to give.

For the past three years a raging bull property market had defined Lebanese confidence but depending on who you talk to the market has either slowed to a halt or dropped by as much as 20 per cent.

The private sector, which usually has the patience of Job when it comes to the buffoonery of Lebanon's political class, is getting impatient and not surprisingly it was a banker that fired the first broadside across the alliance's bows. In an interview with The Daily Star, Francois Bassil, the chairman of Byblos Bank was not mincing his words: "We have had enough of these politicians".

Rekindling memories of 1992 and the civil unrest that brought down the government of the luckless Omar Karami, Mr Bassil suggested that one option to remind the government of its priorities would be to call for a general strike. It was an extraordinary statement from a leading player in a normally conservative and reserved sector.

Still, the ruling alliance believes it can convince us all is well. Mr Bassil's comments came three days after Mr Mikati, doing his best Sepp Blatter impersonation, promised those attending the Arab Economic Forum in Beirut that his government would restore investment confidence.

He will have his work cut out. Only the most blinkered believes that the alliance, which comprises of Hizbollah, Amal, and Michel Aoun's Free Patriotic Movement and a smattering of assorted parties that owe their existence to Damascus, can work together let alone breathe economic life into the country. Mr Mikati's promises belong to a proud narrative among Lebanon's political parties who talk of an economic road map where none exists.

In 2005, when I was editor of Executive, the regional business monthly, in a fit of unbridled naivety we decided to ask all the political parties competing in the forthcoming general election to outline their various economic platforms. You will recall that this was a few months after the assassination of former prime minister Rafik Hariri, the Cedar Revolution and the subsequent withdrawal of Syria's military and intelligence apparatus. Mr Aoun, then the uber anti-Syrian, was about to board a plane after 14 years of Parisian exile and the Lebanese Forces leader Samir Geagea was about to be freed from 11 years of incarceration. Lebanon truly believed it stood at the threshold of a new dawn.

The feedback was underwhelming to say the least.

Not one party had a national vision. No one was gagging to privatise a creaking infrastructure to give tax breaks or incentives to key sectors such as tourism, retail, or agro-industry and there were no calls for making the development of IT a priority.

The parties spoke only in terms of business interest groups and these were defined, not in economic terms, but in relation to the sects the various parties represented. In short, there was, as my colleague, the journalist and economist Thomas Schellen remembers, "no overarching national economic road map". And that was then when confidence was at an all-time high.

The alliance known as March 14 swept to power and without doubt it was the only political grouping that had the potential to effect any meaningful economic change. But given the fact that almost immediately its members were picked off one by one in a series of car bombs and then had to cope with a devastating war in 2006, a terrorist campaign in the north in 2007 and an attempted coup in 2008, that alliance can be forgiven for never really getting into its stride.

So what now?

Ironically, much of the Syrian business community, which owes its success, not to mention its survival, to the ruling Assad regime, wants the Assad family to ride out the current storm. The Lebanese on the other hand are much more resourceful. Watch out for a run on hand baskets.

Michael Karam lives in Beirut