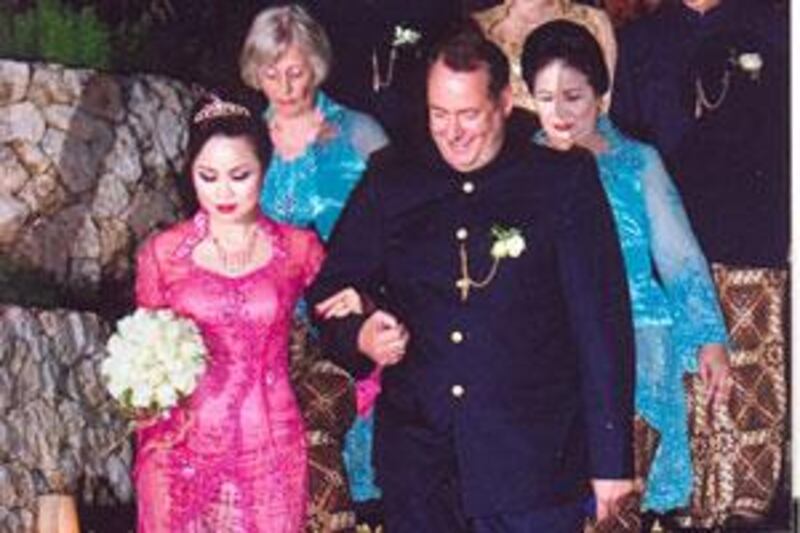

DUBAI // In the photographs of his wedding in the spring of 2007, Martin Bender has the look of a man who has found success. Escorting his Indonesian wife down stairs lined with family and friends, Mr Bender is grinning widely, in a dark blue suit with gold buttons. The wedding cost him Dh250,000 (US$68,000), which seemed a pittance then, considering he was managing director of a Dubai company that built yachts for the super-rich.

Four weeks later, the Hamburg native was in jail. A Dh16 million cheque bearing his signature was presented to the bank, and his accounts did not have enough to cover it. "I thought it was a mistake," Mr Bender, 47, said recently from the Dubai Central Prison in Aweer, where he now wears a prison jumpsuit and has a shaved head. "I had no idea what was happening." The cheque, he said, was supposed to be held as security for a loan from RAK Ceramics to his company, V1 Advanced Composite Technologies, and not cashed until the required funds were present. As he languished in jail, Mr Bender started defaulting on other obligations: a loan from the bank that was used to pay for the wedding, credit cards, money owed to suppliers and employee salaries. He now faces as many as 16 more years in prison. He already has served two.

"The judge didn't care about the circumstances of the cheque," Mr Bender said. "All he wanted to know was if I had signed the cheque. If so, I was guilty." His situation is one of hundreds of cases in which businessmen and individual borrowers face prison for bouncing cheques. In recent months, calls to address these cases through a specialised civil court, rather than the criminal courts, have gained momentum.

Lt Gen Dahi Khalfan Tamim, Dubai's top police official, said in March that bounced cheque cases should be dealt with in a civil court to avoid clogging the system with a "matter that shouldn't have been under our mandate". Nasser Saidi, the chief economist of the Dubai International Financial Centre, said in May that better insolvency laws were needed to reduce the impacts of the global financial crisis.

The threat of imprisonment has led to businessmen fleeing the country rather than settling debts. Simon Ford, the founder of the "gift experience" company Blue Banana, absconded to the UK with his family because, he said, the bankruptcy laws were not strong enough to protect him from jail. In a "letter to the Dubai public", Mr Ford said he would find a way to pay back the money he owed, but could not face the prospect of prison.

Mr Bender says that he also wants to work and pay off his obligations, but that his creditors refuse to meet him about a settlement. "My case is a classic civil case," he says. "Two sides disagree over something. A lot of money is at stake. What you need is an arbitrator to step in. I shouldn't be facing a life sentence." Debt, fuelled by years of easy credit, is becoming a serious problem for borrowers amid the economic slowdown. According to the Central Bank, 544,196 cheques bounced in the first four months of 2009, 5.6 per cent of a total of 9,742,073 cheques issued.

At the core of the issue is the widespread use of postdated cheques and the fact that UAE law considers each bounced cheque or group of bounced cheques as a separate crime. Judges can choose to fine an offender or sentence him to prison for one month to three years for each case. Hassan Arab, the head of dispute resolution at Al Tamimi & Co in Dubai, said he was involved in a case in which a man was sentenced to 67 years in jail for a series of cheque cases. "The reason we approach from the criminal side is to put [the debtor] under pressure to settle the issues," Mr Arab said. "In my opinion, it is much better to settle these cases."

The courts should also spend more time investigating the circumstances of a cheque, especially with security cheques, he said. Security cheques are given to guarantee that one side of a transaction will complete its side of a bargain. They are not meant to be cashed, except in cases where the other party does not fulfil his or her side of the deal. In the same cell as Mr Bender in Dubai Central Prison is a Briton, Peter Margett, founder of a property company called Hampstead & Mayfair.

Mr Margett, 45, was recently sentenced to two years in prison for bouncing security cheques given to investors in return for an investment in his company. He had borrowed Dh22m from 50 investors to build a residential block, but it turned out the person he had bought the land from did not actually own it. When payments came due to the investors, the cheques bounced. He says he has since acquired the land and has secured financing with the hope of moving the project forward and settling the cases.

"It's very difficult to do that from in here," he said. "I need to speak to my clients, but I am only allowed to call 10 numbers. I want to resolve this." What makes matters more difficult, he says, is that he faces more serious charges of creating a fraudulent investment scheme, not just bouncing cheques. He denies those charges. There are laws for companies teetering on the brink of insolvency, but lawyers say that struggling companies usually skirt the courts and work towards compromises with creditors privately, largely because the legal system remains untested when it comes to bankruptcies.

This could have wider implications for the economy, analysts say. "Any sound investor would only want to invest in an economy that provides a dignified exit if things don't work out," said Sumant Batra, president of the association of insolvency specialists, Insol International. Post-dated cheques fundamentally disregard the balance between a creditor and a debtor, he said. "Criminal proceedings should not be allowed to be used by the lenders in the case of these cheques."

"Lenders are supposed to assess projects and financial risk. In the event the business goes bust, they have to accept that this risk was always there. "If it fails, they go through the insolvency system. You either liquidate or restructure so the business can get back on its feet. You can't have your cake and eat it too." Mr Bender recently acquired a uniform with a blue stripe, denoting someone with a shorter sentence, instead of the one he was required to wear with a red stripe, which means he has been sentenced to more than 10 years. Although his sentence has not been cut, the uniform helps him keep a positive view and he is hoping that his creditors allow him to settle.

"I've been able to generate a lot of money in my life," says Mr Bender, who has lost 50kg in jail. "Give me the chance to pay it. Let me work." bhope@thenational.ae