On Saturday, while Lebanon fell apart, I relaxed by the swimming pool of Beirut's celebrated Phoenicia InterContinental. It was the first time I had done so in 39 years, the last time being in the summer of 1973 when, as an 8-year-old, I whiled away the summer at the seafront hotel while my parents got divorced.

Two years later the Phoenicia would become the front line in the first round of fighting in Lebanon's civil war and would remain a bullet-riddled hulk until 1999 when, amid much fanfare, optimism and not a bit of nostalgia, it reopened. Lebanon was gearing up to receive the first wave of high net worth Arab tourists and the Phoenicia was ready to receive them.

But in the years before that, I would drive by wishing I could peer into the deserted pool area, filled with what I imagined were the ghosts of well-heeled Lebanese and the militiamen who usurped them to fight and die in what became known as the battle of the hotel district, a time when gunmen in 1970s disco gear would ostentatiously celebrate any "military" gains with bottles of champagne looted from hotel cellars.

Across the road from the Phoenicia is the St Georges. Arguably a more historic hotel - its bar was a magnet for the spies, bankers, diplomats and journalists we all now love to believe shaped the Middle East over dry Martinis and endless cigarettes - to my 8-year-old eyes it lacked the Phoenicia's pizzazz.

Today the St Georges is still a shell, creaking first from the effects of war and then the huge blast that killed the former prime minister Rafik Hariri in 2005.

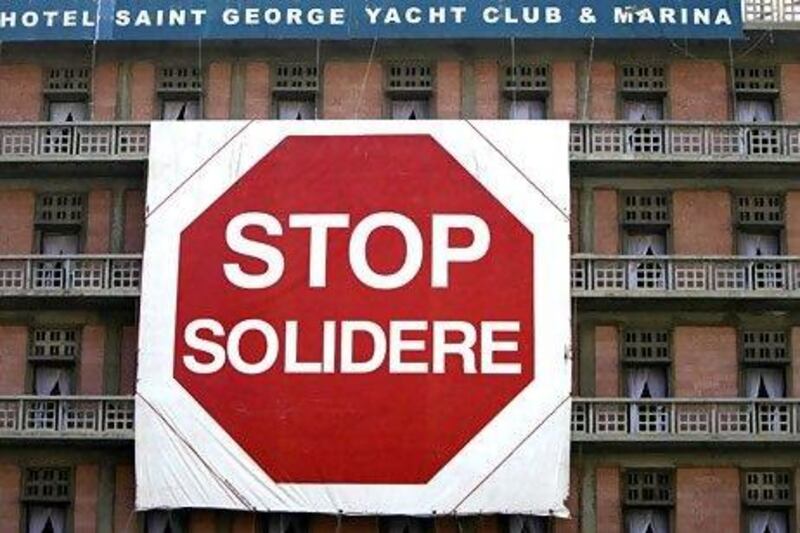

The hotel's owner, Fadi Khoury, does, however, run a successful beach club adjacent to the old building, even if, for nearly 20 years, he has been locked in a high-profile legal battle over expropriation rights with Solidere, the property development company that rebuilt the centre of Beirut.

For the past decade a huge "Stop Solidere" banner has been draped over the east-facing façade of the building.

Mr Khoury recently added another sign, in English, French and Arabic, reminding people they are in St George Bay and not Zeytouni Bay, the neighbouring development that has, in the past six months, become the epicentre for Beirut dining and leisure.

The name does have some relevance. Zeytouni was the name of the nearby prewar red-light area, which has been transformed into an upmarket residential district. It is appropriate that Zeytouni Bay is named after an area that represented the seedier side of Beirut's supposed golden age.

In many ways the Lebanese capital is still an ageing, but much loved, hooker whose clients visit more out of affection than anything else.

But this year their patience is wearing thin. With Ramadan looming and a veto slapped on Lebanon by many of the GCC nations, the country's tourist season is over before it has begun.

On Sunday evening, the Beirut Central District, the jewel in Solidere's crown, was almost deserted at a time of year when finding a table would normally be something of an ordeal.

And who can blame the absent visitors? This week, we were warned that the country's electricity grid is heading towards meltdown and more roads have been blocked in what has become a national expression of dissent.

Lebanon used to be the Arabs' home from home, a country that offered something a bit different and a bit racier but which spoke their language and understood their habits.

But what with Syria next door and the country's glaring inability to pull itself together and deliver the basics, this year the Arabs have chosen to holiday in Turkey, a Muslim country that knows what it has to do on all levels to be a regional player.

The Phoenicia and the St Georges will carry on doing what they do best - and hope for the best.

They should know. They've seen it all before.

A Michael Karam is the associate editor-in-chief of Executive, a regional business magazine based in Lebanon