Andy writes a reasonably good account of his recent skiing trip, for someone just eight years old.

Fact Box: Read more from The National's Abu Dhabi Model Economies

250 yuan Cost of one month of English lessons, once a week, with the English school Talenty

15 billion Total value in yuan of the English-teaching market in China in 2009.

2 Age of the youngest children taught by Disney English.

9,900 yuan cost of an intensive four-week Mandarin course in Beijing.

"I reached the top of the snow and looked down. Wow! It's so cliffy! I carefully skied down. Suddenly I fell over. It hurt me badly, but I didn't give up," he wrote.

While not perfect, it is impressive considering that Andy is Chinese, and not someone who has spent his early years listening to his parents converse in English. Pictured giving a peace sign alongside his little report in a brochure produced by the English-teaching company Talenty, the youngster is one of a vast band of Chinese people learning what has become the world's lingua franca.

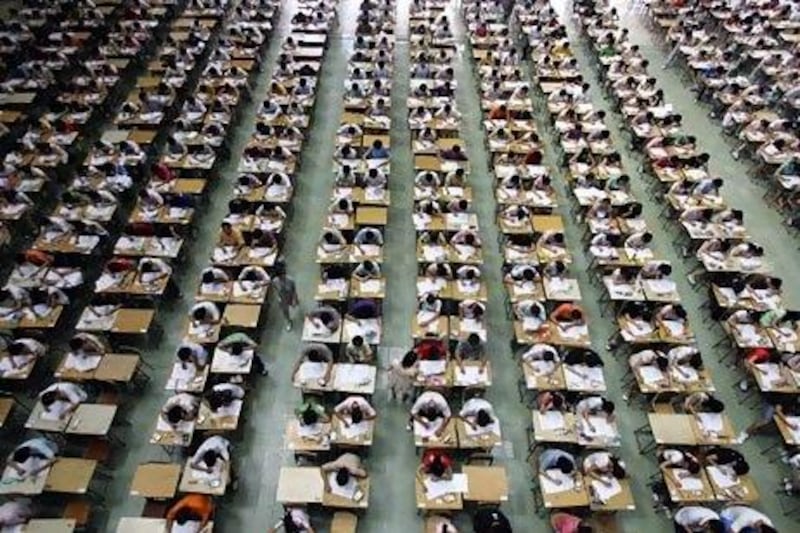

In a speech two years ago, the Chinese premier, Wen Jiabao, said there were 300 million people in the world's most populous nation studying English.

Teaching English is a big business in China because, although all schoolchildren are supposed to take lessons in the subject from the age of six or seven, many parents believe it is worth paying for extra classes. Concerns are often raised that English is taught in schools with a view to just passing exams, so without additional training, children may lack the ability to communicate properly.

The fact that most newly well-off middle-class parents have only one child is another reason why no expense is spared.

As well as the children learning English are thousands of adults, many of them business people, taking intensive English courses.

According to figures reported in state media, the English-teaching industry was worth 15 billion yuan (Dh8.61bn) in 2009, and total revenues are increasing as much as 15 per cent annually. Estimates suggest 30,000 institutions in China offer English training, some online.

"The number of students is increasing year by year. Everyone has to learn English," says Ge Qiuyan, a training manager for Talenty in Changchun, a city in north-east China.

"They have to write reports or articles, see films and travel. For these, learning English is very important. For kids, they have to start very young."

Many senior business roles in China now require people to speak English, says Angel Lin, an associate professor in the faculty of education at the University of Hong Kong and co-author of the book Classroom Interactions as Cross-cultural Encounters: Native Speakers in EFL (English as a foreign language) Lessons.

"If people want to do international business or [work for] a joint venture, then because of globalisation you will need to speak some English, but most people are quite innovative - they can pick it up on the job," Dr Lin says. "If you want to become top management then increasingly, with globalisation today, you will have to be proficient in English."

While visitors to China often have difficulty finding people with whom they can communicate in English, the language is more commonly spoken than in previous decades. Then, an isolationist foreign policy and ties to the former Soviet Union meant that Russian was often seen as more important.

"If you compare the situation in China [now] with 20 or 30 years ago, you will find China has made a lot of improvements in terms of teaching foreign languages," says Tam Kwok-kan, a chair professor in the school of arts and sciences at the Open University of Hong Kong and the co-editor of the book English and Globalization: Perspectives from Hong Kong and Mainland China.

"I remember 30 years ago when you went to China for a conference, most people could only speak Chinese. Now you can easily find people who speak English, especially academics. Most of them have no problem with English."

The 2008 Olympics gave China a spur to increase its number of English speakers, and there has been no sign that the momentum has been lost, with both Chinese and foreign schools expanding.

Talenty, for example, says it has more than 6,000 students just in Changchun, one of more than 10 cities in which it operates.

One of the largest English-training companies, POP Kids Education, has 350 locations that together generated 500 million yuan in the first five months of this year. Such has been the success of the company in the seven years since it was founded that franchised operations are now set to be launched.

Just over two years ago, Pearson said it was paying the Carlyle Group US$145m (Dh532.6m) to buy a chain of 39 colleges run by the Wall Street Institute.

The US film studio Disney has become one of the most high-profile operators. In less than three years it has expanded to the extent that it now has more than 20 centres in China for children as young as two. The company's method of incorporating Disney characters such as Mickey Mouse into lessons has sometimes been criticised as a marketing exercise, but the undoubted strength of the brand attracts parents.

Native English speakers from countries such as the UK, US, Australia and Canada are employed by both Chinese-owned and foreign English-language schools. A typical salary for a full-time foreign teacher at a Chinese-owned language school is about 5,000 yuan a month, with accommodation provided free.

The industry's expansion has posed challenges. The growth of large corporate language schools has pressured smaller operators, many of which have gone bust in recent years in the face of rising rents and pressure to keep down course fees.

Also, the sector can seem confusing to parents because of the vast array of schools and the widely varying fees. Zhong Yongqi, the president of Global Education and Technology, one of the major school operators, recently told state media the industry was "in chaos" because so many companies were "rushing into the market".

Dr Lin acknowledges there are difficulties, but is optimistic the situation will stabilise. "The China market is so big and the bigger the market, the more difficult it is to have quality assurance," she says.

"I think the authorities in China in the long run will have some systematic policies to deal with the quality.

"The students, the people themselves will have word of mouth, they will tell which ones are better, which ones are more qualified. Things will sort themselves out."